Food and dining have been central to the culture of the Middle Temple for the whole of its recorded existence. However, the nature of the meals, the manner of service and the method of the supply of food and drink has altered considerably over the centuries. This topic being so vast in scope it must be addressed in several parts, starting with a look at the earliest records of the Society from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to reconstruct the organisation of catering at the Inn during this period.

The kitchen was not always in its present location and has moved more than once during its existence. It might be expected to have been situated near the site of the old Hall, which is thought to have been on the east side of Middle Temple Lane, extending as far as the no longer existent Vine Court and possibly on the site of Pump Court. However, the location of ‘the old kitchen’ is recorded in 1561 as having been ‘near the Gate, under the chamber of Lord Stafford’, which is a considerably further distance up Middle Temple Lane at the entrance opening up to Fleet Street. As construction of Middle Temple Hall is only supposed to have commenced in 1562, it is possible that there was a move to a second, more practically located kitchen before a new one was created for the new Hall.

Plan of the Temple copied from John Ogilby’s map of London, 1677, with the possible location of the old Hall outlined in red

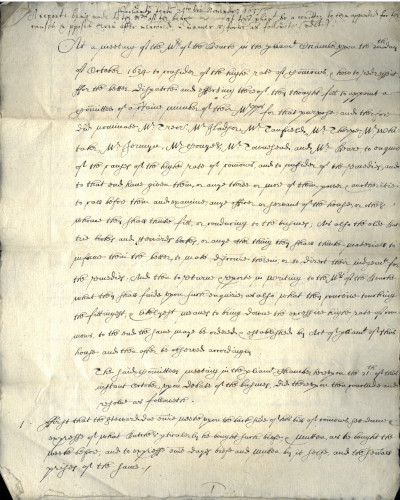

The Steward was the highest-ranking servant of the Inn after the Under Treasurer with the greatest level of responsibility and the highest wages. While his primary activity was collecting payments for ‘commons’, as dinners used to be known, he was also responsible for sourcing ‘sweet and wholesome victual’ and other necessaries for the running of the Inn and overseeing the other servants. Unfortunately, he was not always successful in ensuring that catering at the Inn was well run, and in 1637, and several times in the early 1660s, committees were formed by the Benchers to investigate ‘the affairs of the market, kitchen, cellar and buttery’ for the ’discovery of abuses, and to make proposals for reducing [the cost] of commons’. While the 1637 committee was mainly concerned with ensuring an accurate record was made of deliveries, specifying measures and restricting access to storage areas, the complaints in the 1660s were more serious. A particular complaint levied at the Steward was that he was not always reliable at sourcing decent ingredients, and that the meat that he bought – beef and mutton – was often rotten. As a result, this duty was removed from his hands and passed to the Cook, who from this point both sourced and cooked ingredients.

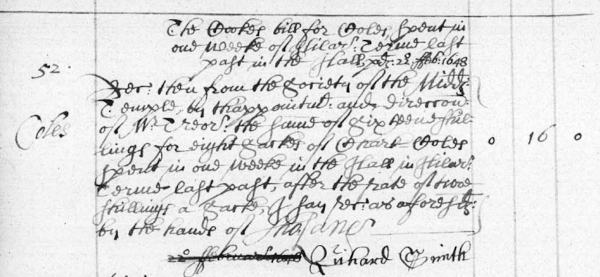

Report of the Committee on Commons, 24 November 1637 (MT/7/MIS/1)

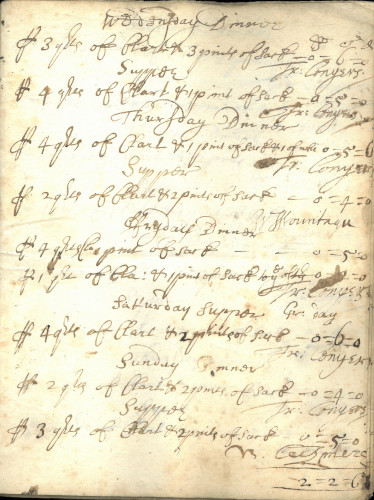

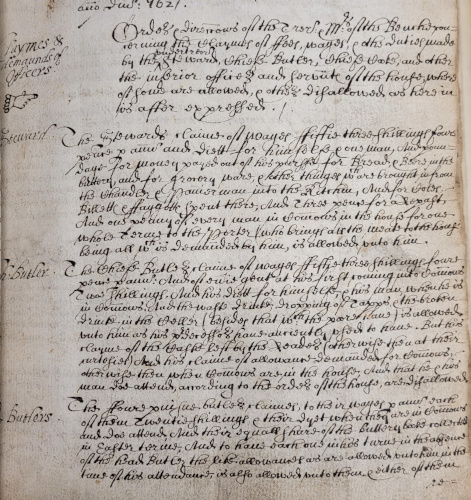

Below the Steward in importance were the Chief Cook and Chief Butler, the latter of which at this time denoted a servant with charge over the wines and liquors of an establishment. The kitchen was the domain of the Chief Cook, who provided cooked meals to the Society, and the Chief Butler was responsible for the buttery, where drinks such as beer and wine were stored as well as other provisions such as bread that were bought in rather than made on-site. It was also where many of the catering and dining records were kept. The Chief Butler was also charged with accepting and recording the delivery of bread and with locking the bread bin. He took in and recorded deliveries of beer with his assistants the Puisne Butlers, numbering four in 1637, who assisted in his record-keeping and tilting the beer so it had time to settle before it was drawn.

Booklet recording the daily consumption of claret and sack, now known as port, at dinner and supper, Michaelmas Term 1673 (MT/7/WBA/4)

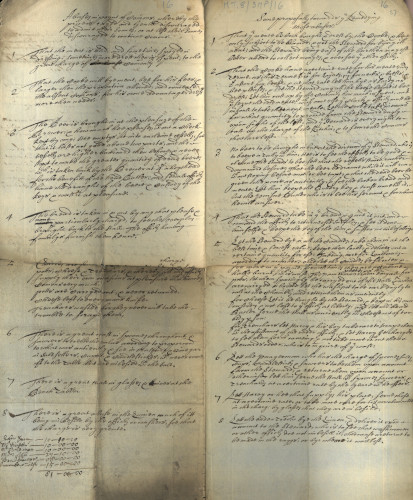

The buttery was included in the criticism levied by the c.1660 committee, who complained that the brewer was allowed to bring in as much beer as he wished, completely unchecked, and in unclean vessels so it went off quickly. The servants were also accused of mistreating the beer barrels to make the beer go off faster. This was supposedly so that the dead beer could be sold back to the brewer at 4 s. a hogshead for the benefit of the Head Butler. They buttery servants were also criticised for leaving the bread available for anyone to take and that ‘cheese [was] left to every man’s knife’. After this report the following reforms were suggested: that no beer was to be bought in except by direction of the Steward, who was to keep a record, and that the vessels were to be clean and stored appropriately; that any dead beer be given to the poor ‘as anciently’ rather than sold back to the brewer, ‘as so the broken bread and meat’; lastly, that the Steward was to keep the Buttery key and trust it to nobody but the Puisne Butler ‘who is to be his servant and for whom he will answer’.

List of abuses of commons and suggested remedies, c.1660 (MT/8/SMP/16)

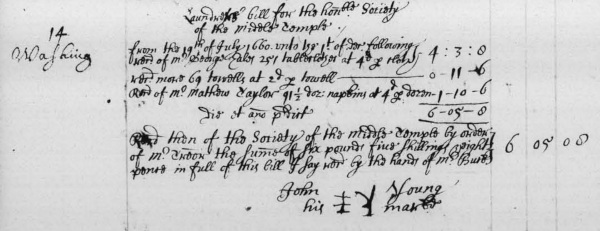

Another duty of the buttery servants was the keeping of the Inn’s linen, as it was customary during this period to cover dining tables with a linen tablecloth, in contrast to the bare wood favoured today, and to provide napkins to the members. Though it is probable there was linen in use by the Inn before this time, the first written evidence of table linen is found in the minutes of 12 October 1627 where the Master Butler was ‘charged with the linen for the Hall, and the second Butler with the linen for the Bench table. Inventories therof shall be made and examined yearly’. A receipt dated 11 May 1639 shows that 24 tablecloths and 72 napkins were made and marked by a seamstress that year alone, and keeping the linen clean provided a great deal of work for laundresses – a bill from 1660 for example shows that between July and December of that year they washed 251 tablecloths, 69 towels, and 1098 napkins.

Receipt for the washing of table linen by laundresses, 1660 (MT/2/TRB/19)

The Chief Cook was the head of the kitchen and was allowed to keep a manservant to assist him with his tasks. He held a position of great responsibility and was compensated accordingly. In 1628, he was paid a generous annual wage of 53s. 4d. - in comparison the kitchen’s Turnspit was paid 26s. 8d. each year. He was also entitled to other benefits, such as meals for himself and his servant; dripping from the meat prepared in the kitchen; the kidneys from loins of mutton; 5s. for sauce and jelly; a bonus of 13s. and an apron as payment from the Stewards of the Reader’s Feast. Despite this allowance, there were accusations of financial malfeasance levied toward the cook in the c.1660 report, which accusing him of cooking too much food and using the leftovers for his own profit. He was subsequently instructed to take instruction on how much to cook from the Steward each day.

Woodcut of a stout cook in his kitchen, 1530 © The Trustees of the British Museum

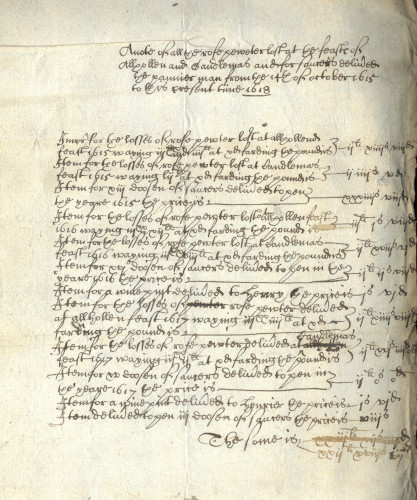

An additional responsibility of the Chief Cook was for the care and security of the pewter plate of the Society. Prior to 1724, most of the membership dined from wooden trenchers. The Benchers had the use of pewter plate, which was favoured by the upper classes before fine ceramics gained popularity in the 18th century. However, this would have had the unfortunate effect of leaching poisonous lead into their bodies, the evidence for which can still be found in the bones of the upper classes of this time. The first mention of pewter vessels in the Minutes of Parliament is in those of 28 November 1581 when the Master Cook was paid 10 shillings to take care of the pewter and would be charged for any spoiled or lost. By 1618 it appears that this responsibility became too burdensome for the Cook to bear, as many pewter vessels were carried away during the two annual Readers’ Feasts. On the 27 November the Cook was ‘allowed towards his losses’ and the Readers were ordered to ‘bear the cost of hire and loss of pewter vessel used for the Readers in reading times’. The Chief Cook still continued to be responsible for the care of the pewter plate at all other occasions.

Pewterer’s bill for all the rose pewter lost during the feast of All Hallows and Candlemas and for saucers delivered to the pannierman from 14 October 1615-1618 (MT/2/TUT/10a)

There was also an Under Cook appointed by the Inn to assist with the cooking. In addition to his wages in 1628 he was granted the ashes from the kitchen fire, the ‘kitchen stuff’, meals and a part of the broken meat. The two cooks were also granted the use of chambers opening onto the woodshed next to the garden. Additional staff that populated the kitchen were two turnspits who worked at the times of the Lent and Autumn Readings to roast meats, reduced to one during the rest of the year - they were granted a loaf of bread at every meal, a pot of beer and part of the broken meat in the Hall together with the Under Cook. The lowest status servant in the kitchen, ‘an old woman to wash the dishes’, appears to have been given no extra allowances.

Mezzotint of a sleeping old maid sitting before a washtub full of cooking utensils, 1660-1675 © The Trustees of the British Museum

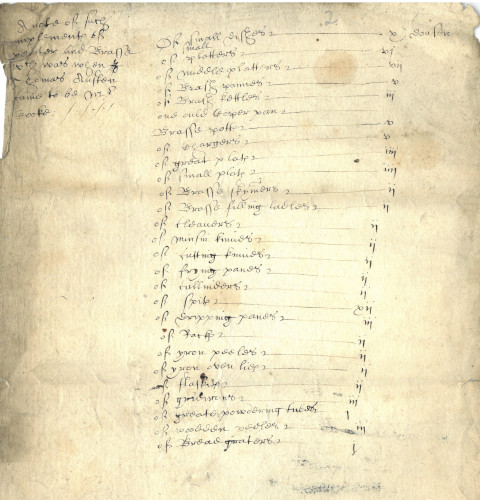

The kitchen had to be well outfitted in consideration of the large numbers it was catering for. Inventories survive from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the earliest one dating from 1554. They show that the kitchen was arrayed with dozens of platters and dishes and that the favoured material for pots and pans was brass. There were many utensils for tending and cooking over fires, such as spits, pot hooks, fire shovels and dripping pans. By 1609, two iron oven lids were included in the inventory of the kitchen utensils, suggesting that there may have been at least two ovens in the new kitchen. By the end of the century the number and type of kitchen implements had expanded considerably and included a leaden cistern, presumably to store water. There was also a separate larder containing scales and a powdering tub for salting and preserving, and a pastry room for creating sweet dishes and locking valuable sugar away.

Inventory of kitchen implements c.1609 (MT/8/SMP/2)

Cooking at the time was done over fires and this required a great amount of fuel. The fuel used for much of the cooking was referred to as coal, but records may have been using outdated language referring to ‘char coal’ rather than dirty pit or sea coal, with faggots of wood used for starting the fires. Billets of wood, standardised in the 16th century to 3ft. 4 inches in length and ten inches around, were also purchased, probably for burning in heaths and using for roasting meat on the spits. There was a coalhouse and woodhouse on site and in 1637 the Chief Cook was made responsible for recording all the fuel of the Inn that was bought and daily expended.

Receipt referring to the use of ‘char coal’ for heating the Hall, 2 February 1649 (MT/2/TRB/7)

There were other servants involved in the food service that were not tied directly to the kitchen or buttery. Some of these were men appointed as Washpots to the Society, a Chief Washpot and one or two Under Washpots. These servants had duties that aligned most with modern waiting staff - they gathered the dirty dishes, drew beer from the cellar, waited on the Masters of the Bench at table and cleaned the cellar and the buttery. In addition to his wage, the Chief Washpot was also granted the remainder of one of the best messes of meat from the Bench Table and bread and drink for his own meals, whereas the Under Washpots were only entitled to ‘part of the broken bread, besides that given to the poor, and the leavings of the meat which comes from the clerks and officers’. The Washpots escaped direct shaming in the c.1660 committee report, but it is implied that they were remiss in their duties as pots were carried out and never returned and trenchers were wasted as they were never scraped as was customary after each course.

Orders and directions of the Treasurer and Masters of the Bench concerning the claims, fees, wages and other duties made by the Under-Treasurer, Steward, Chief Butler, Chief Cook and other officers and servants, 27 June 1628 (MT/1/MPA/5)

The first mention of the position of Pannierman in the Inn’s minutes was in 1624 – his role appears to have involved in taking delivery of and distributing various items such as pots, dishes, glassware, salt and sauce. He served food provided by the Steward into the Hall, obtained candles and other light sources from the chandler and recording the distribution and use of these. He was also obliged to carry in and out cushions for the Bench Table as part of his wage, despite his demand for an extra 5 shillings a year in 1628 to undertake this duty.

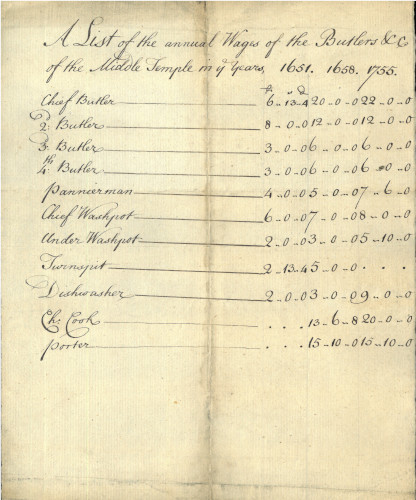

A comparative list of annual wages of the servants of the Inn in 1651, 1658 and 1755 (MT/8/SMP/80)

While fashions in dining would have changed over time and the outfitting of the Middle Temple’s kitchen changed to reflect this, there were some principles of food service that appear to hold true throughout the centuries. The organisation of the kitchen and buttery were the key to successful catering at the Inn and to satisfying the membership. As in the present day, maintaining control over stock, keeping thorough records and choosing reliable servants appears to have been vital to achieving this, as demonstrated by the interventions of the Benchers when lax standards and corruption crept into the organisation of this vital function.