Due to the Inn’s primary role as an educational and collegiate institution for barristers, it is sometimes easy to overlook its history as an employer, which dates back to its very inception. The stories of some of the Inn’s early staff were explored in the previous articles, including the ones on Steward and Porter. This month we build on these to highlight the lesser known experiences of Middle Temple staff in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in a hope to understand more about the working conditions of these perhaps rather obscure figures.

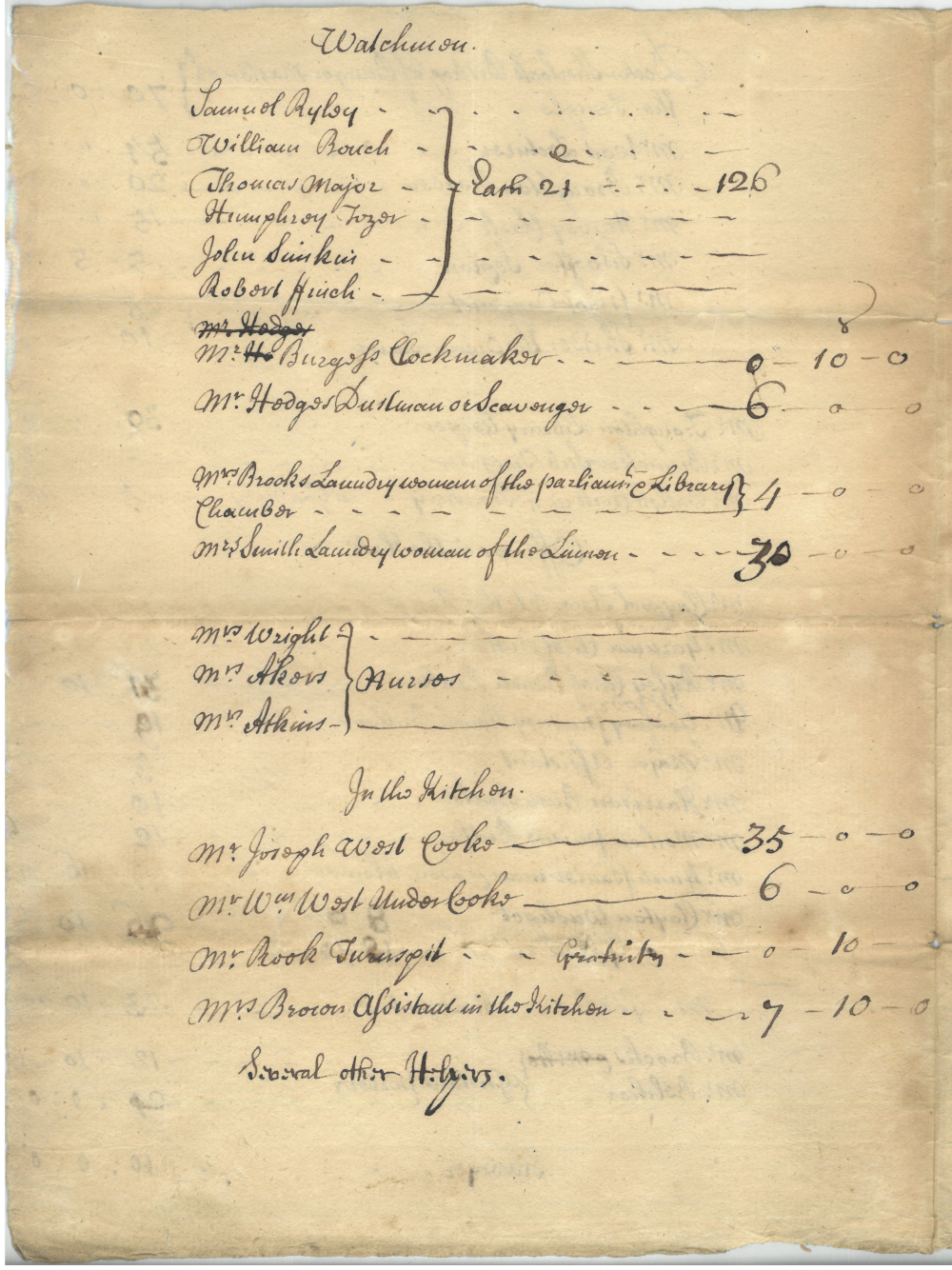

List showing officers and servants employed at the Inn and their annual salaries, [1730s] (MT/8/SMP/17)

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a variety of officers and servants were employed to support the Inn’s key functions, which included delivering educational activities and providing meals in Hall – often known as ‘Commons’. Hall officers, at one time comprising a Steward, Panierman, Washpot, Hornblower and Butlers of several ranks, worked alongside the Cook and other servants in the buttery. Inside and outside Hall, Porters and Watchmen were tasked with overseeing safety and security across the Inn. There were also auxiliary roles catering various domestic functions, such as nurses, laundresses, scavengers and other helpers.

Illustration depicting the tradition of blowing a horn to summon members for dinner by a hornblower, 1921 (MT/19/ILL/F/F4/9)

In return for their service, staff were compensated in various ways. Servants and officers received wages, and depending on their ranks some were entitled to additional allowances. These benefits could include meals, the right to occupy chambers, rent relief or other provisions. The Chief Butler, who facilitated learning exercises and assisted the Steward in providing commons, for example, received a free chamber, commons for himself during term time, chippings of bread, ‘the wast drink droppings of the taps, and broken drink in the Cellar’. On special occasions such as the Reader’s Feast and Grand Day, officers were also given wine.

Extract of a note showing the amount of wine given to each officer in the buttery on special occasions by the Masters of the Bench, C18th (MT/8/SMP/39)

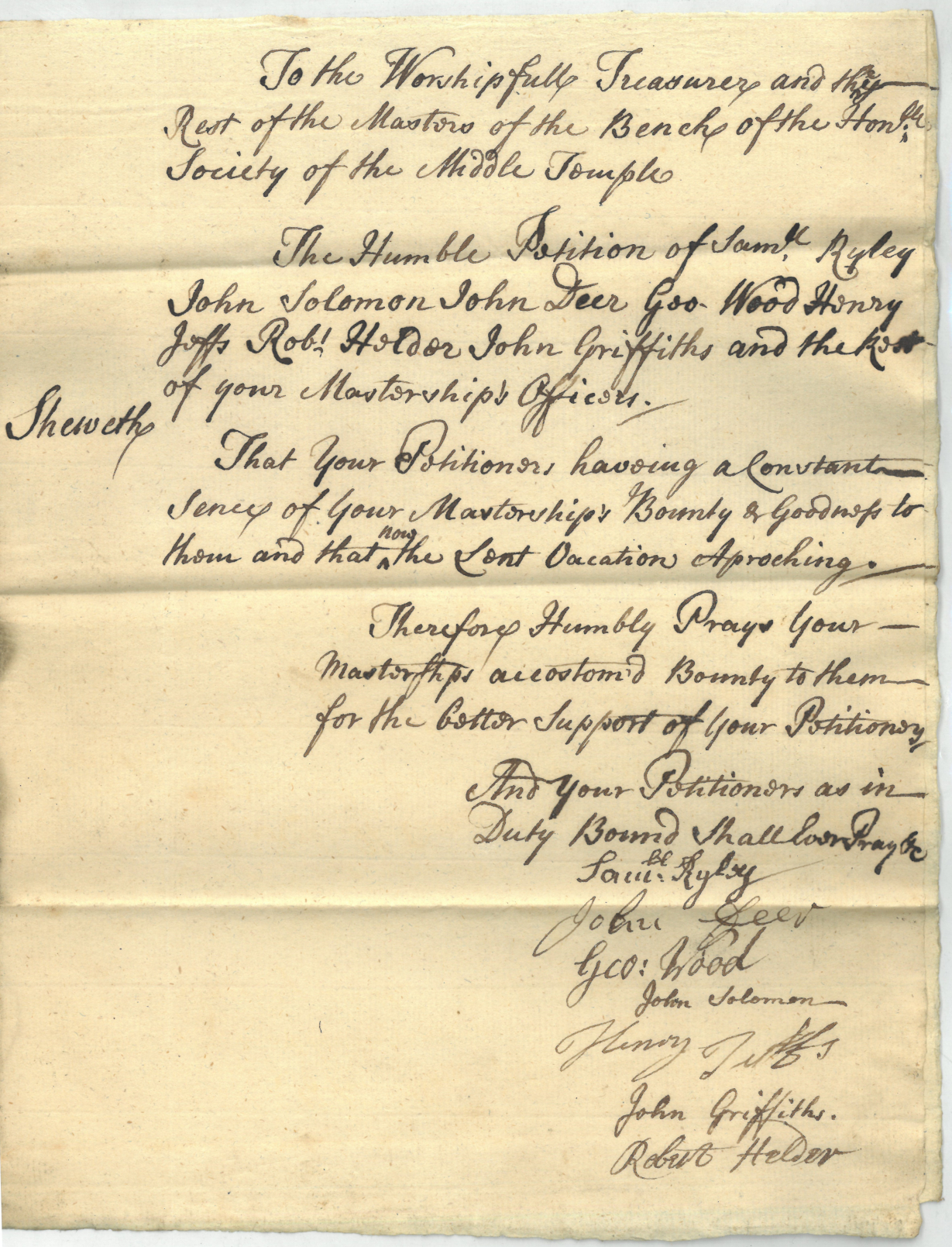

During the late seventeenth century, it became customary for the Inn to grant what was called the Long Vacation gratuity to Hall officers between terms. The gratuity was first allowed in the 1650s to compensate officers’ financial loss due to the disruptions to learning activities and commons caused by the English Civil War, as they had previously taken a share of the charge paid by members who dined in Hall and failed to perform their exercises. This compensation, ranging from a few shillings to several pounds per officer, soon became a standard practise even after the resumption of commons, with many instances in the minutes of Parliament noting that Lent gratuity be paid ‘as usual’ and, later, for ‘better support’ of the officers and their families.

Petition signed by several Hall officers for the Inn’s better support during the approach Lent Vacation, 1759 (MT/21/1/1)

While the Inn appeared generous in its remuneration, employment at the Inn was not without its strict conditions. Many Hall officers and kitchen servants were obliged to sign a bond, similar to a modern contract, upon taking up their roles. By signing this bond, the employee became officially ‘bound’ to the Inn and pledged a sum of money as security for their satisfactory performance, which they had to pay if the Inn decided to put the bond in suit. The required security varied according to the rank of the role: Hall officers such as Butlers were typically required to pledge £200, while the Steward had to provide as much as £500 – this would be worth more than a hundred thousand pounds today.

Document recording the condition of the bond given by the Bar & Puisne Butlers for a security of £200, [late C18th] (MT/8/SMP/96)

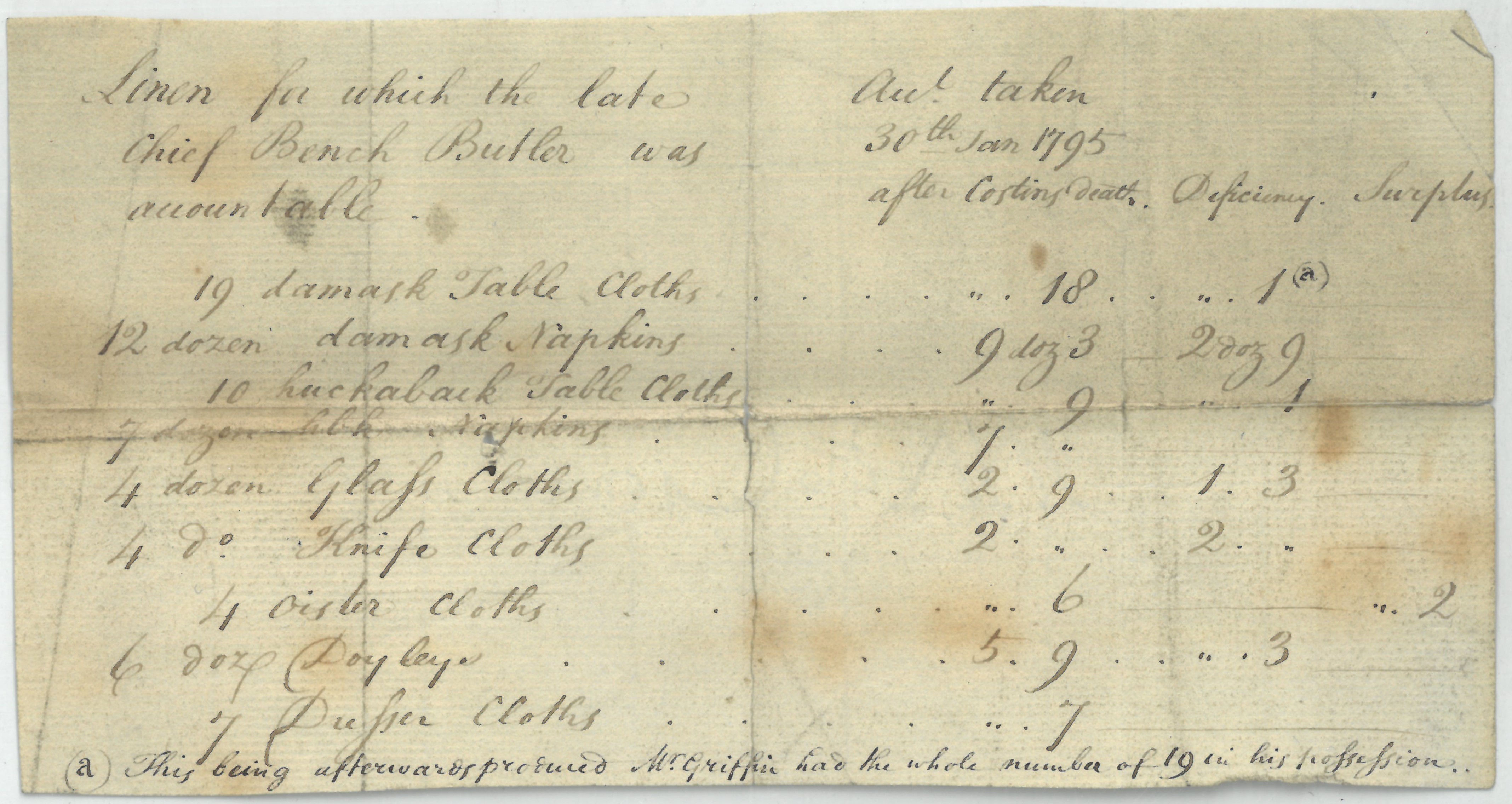

A bond was necessary because many staff would have direct access to the Inn’s finances and property in their everyday work. Hall officers such as the Steward and Butlers collected payments for commons and learning exercises from members, while also looking after articles like silver plates, wine, cloths and other utensils. The Inn took this matter seriously – the accounts of these staff were frequently scrutinised and audited by the Inn, while inventory lists were produced from time to time to itemise the articles in their possession. An inventory taken in January 1795, for example, indicates that several damask table cloths and napkins as well as multiple huckaback, glass and knife cloths were missing during the tenure of the Chief Bench Butler.

List of linen under the custody of the late Bench Butler and account of it taken after his death, January 1795 (MT/8/SMP/98)

Failure to safeguard property could risk financial consequence and even dismissal. According to an order in October 1683 the Butlers and Bench waiters were expected to replace the lost linen under their custody out of their wages. Going into the eighteenth century lost property remained a persisting problem for the Inn. In 1778 Parliament noted that pewter of the House frequently went missing, with a veiled admonishment that these incidents could not happen without the knowledge of some servants. It was ordered that staff who took away any dishes, plates or other utensil be dismissed going forward.

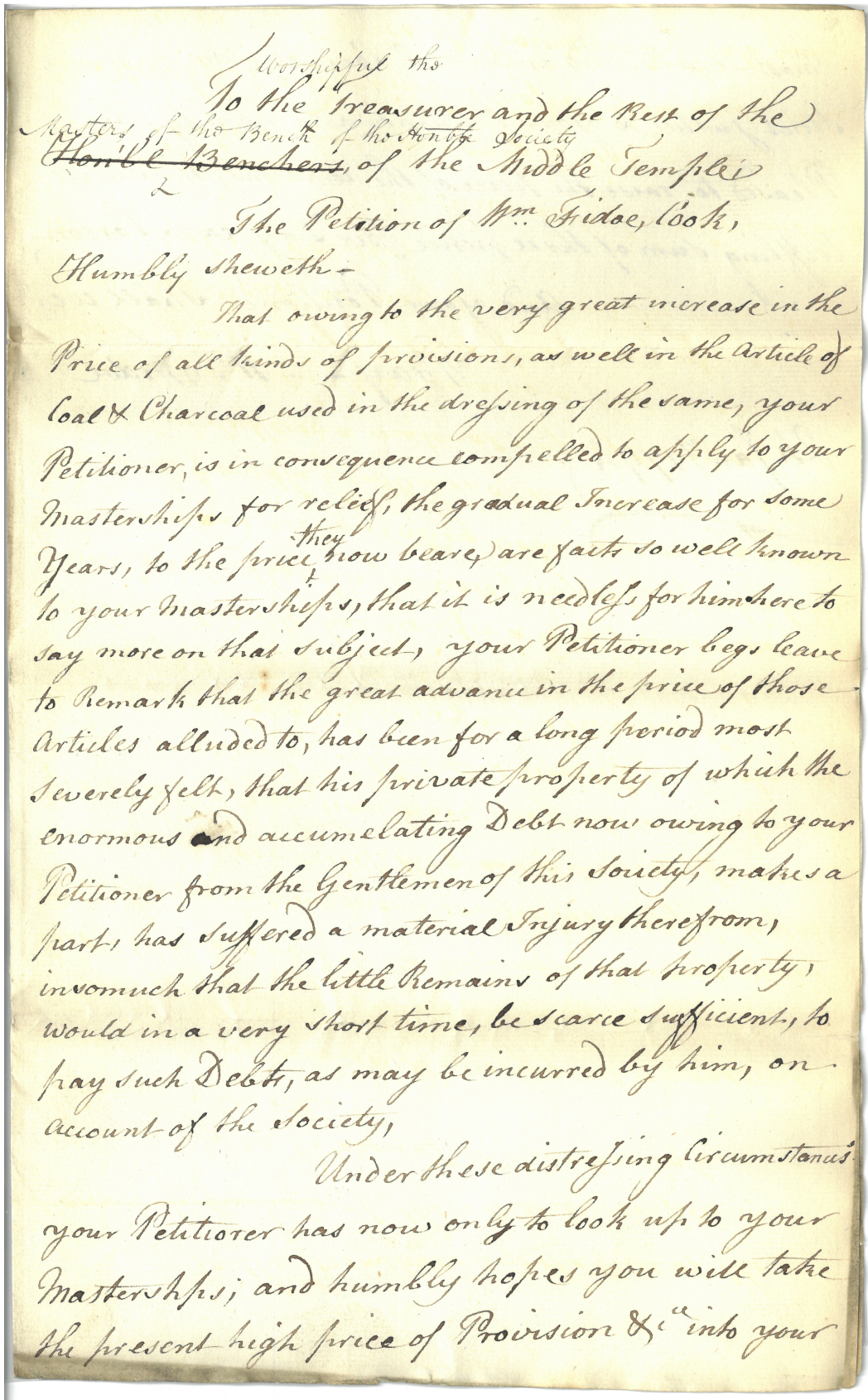

In addition to the risk of having to make up for the lost property, working at the Inn could bring other financial burdens for some individuals. Such was the case for John Best, Porter, who in 1659 wrote that he had been paying 2d per night on candles out of his own pocket for the past five years, an accumulative expenditure exceeding his annual salary which was £15 10s. Similarly, staff could run into debt for supplying commons. One occasion was in 1794, when the Chief Cook, William Fidoe, felt compelled to ask the Inn to raise the charge of commons to cover the increasing cost of kitchen provisions and articles, admitting that the ‘enormous and accumulating debt’ – resulting from the huge arrears of members – had affected him so much that his private property ‘suffered a material injury’.

Extract of petition of William Fidoe, Chief Cook, to apply for relief due to the great expense of coal and charcoal, 1794 (MT/21/1/1)

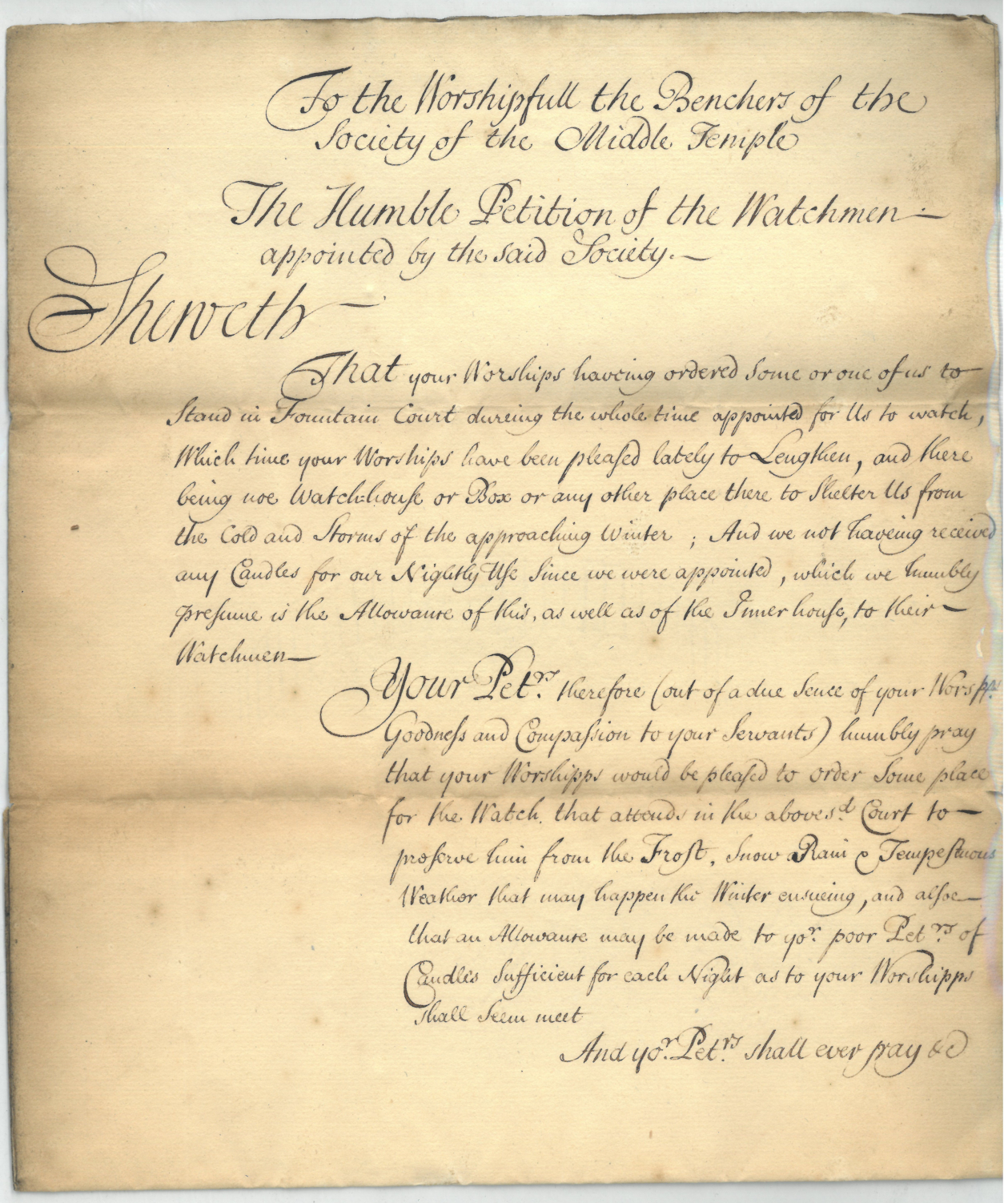

An important source offering fascinating insights into the working lives of staff during this period comes from the numerous petitions submitted by them. Many staff, over the years, spoke up and requested for improvements to their working conditions: these often came from watchmen and porters whose duties required them to be outdoors for long hours. In early eighteenth century, for example, a group of watchmen petitioned for a place in Fountain Court to shelter from the ‘frost, snow, rain and tempestuous weather’ in the coming winter as well as sufficient candles for their use, as they received none now. Extreme weather was the subject of another petition by watchmen in January 1789, when severe frost had added much hindrance to their work. The winter of 1788–1789 was one of the coldest Europe had witnessed in three centuries, and the watchmen’s request was met with the Inn’s bounty – each was granted £2 for their service and for clearing snow in several courts.

Petition of the Watchmen for a place to shelter and being granted an allowance for candles sufficient for their use, [C18th] (MT/21/1/5)

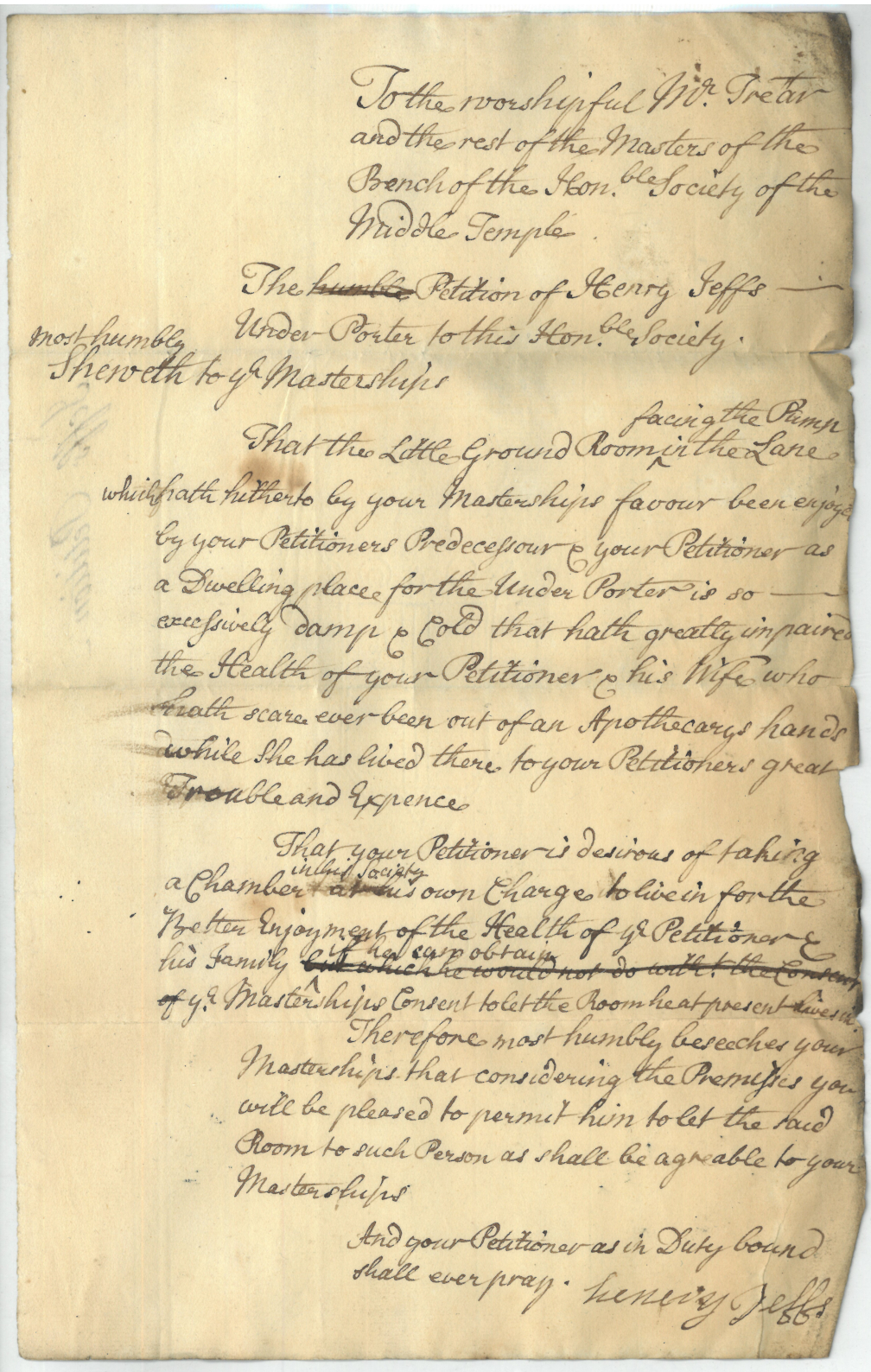

Employment allowances provided by the Inn could sometimes create new problems too, as they might not always meet everyone’s expectations and could lead to inequality. In November 1744 the Under Porter, Henry Jeffs, wrote that the room he was assigned for dwelling in Middle Temple Lane was ‘so excessive damp and cold’, and that his and his wife’s health had suffered so greatly that ‘they are scarce ever out of the hands of an Apothecary’, asking to be allowed to move to a room on the Library staircase.

Petition of Henry Jeffs, Under Porter, for relocating to the room on the Library staircase due to the conditions in his assigned chamber, November 1744 (MT/21/1/1)

Unforgiving chamber conditions were once again mentioned in a petition by Richard Ingall, Chief Bench Butler, and Thomas Pearce, Washpot, in January 1771. Despite both being ‘very ancient officers,’ they did not enjoy the privilege that some other new servants were granted: dining in the buttery, where a fire was allowed to keep the staff warm and comfortable. One might be able to read the bitterness between the lines, as they wrote how they were ‘obliged to feed upon cold victuals in a damp cellar’ and asked to be allowed commons with the rest of their ‘brother officers’ in the buttery.

Although male staff dominated the Inn’s workforce in this period, some of these early accounts on the working lives of staff were contributed by female members of staff, who took on a range of roles such as laundresses and scavengers. One of the earliest records associated with a female member of staff preserved in the Archive was a petition signed by Mary Petty, a kitchen servant responsible for washing pewter. In 1681, she requested a pay rise to compensate her increased workload from also having to wash plates. Perhaps recognising Petty’s loyal and satisfactory service of 16 years, the Treasurer deemed it fit for her wage to increase by 20 shillings per annum.

An 18th-century engraving depicting a scullery maid, a female domestic servant responsible for washing dishes, © Metropolitan Museum of Art

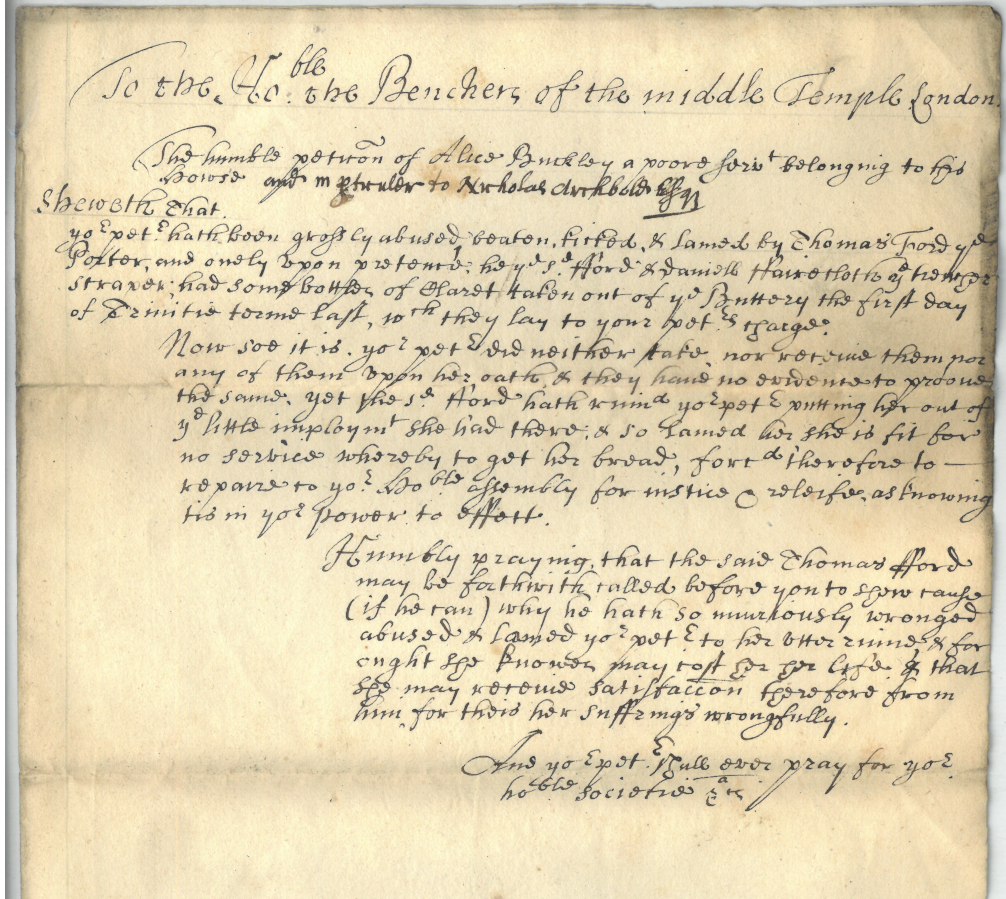

The experience of other female staff at the Inn, however, can be quite distressing. One particularly upsetting example was from Alice Buckley, a laundress employed by the Inn who seems to have worked for Nicholas Archbold, Lent Reader for 1684. In her petition she claimed that she had been ‘grossly abused, beaten, kicked and lamed’ by Thomas Ford, Porter from 1671 to 1694, following what appears to be a false accusation of her smuggling some bottles of Claret out of the buttery by the Porter. Although Buckley pleaded the Porter be called before the Masters of the Bench to ‘show cause’ of his action, no further record of the incident can be found in the minutes of Parliament.

Petition of Alice Buckley, Laundress, stating the mistreatment she received from the Porter, [late C17th] (MT/21/1/2)

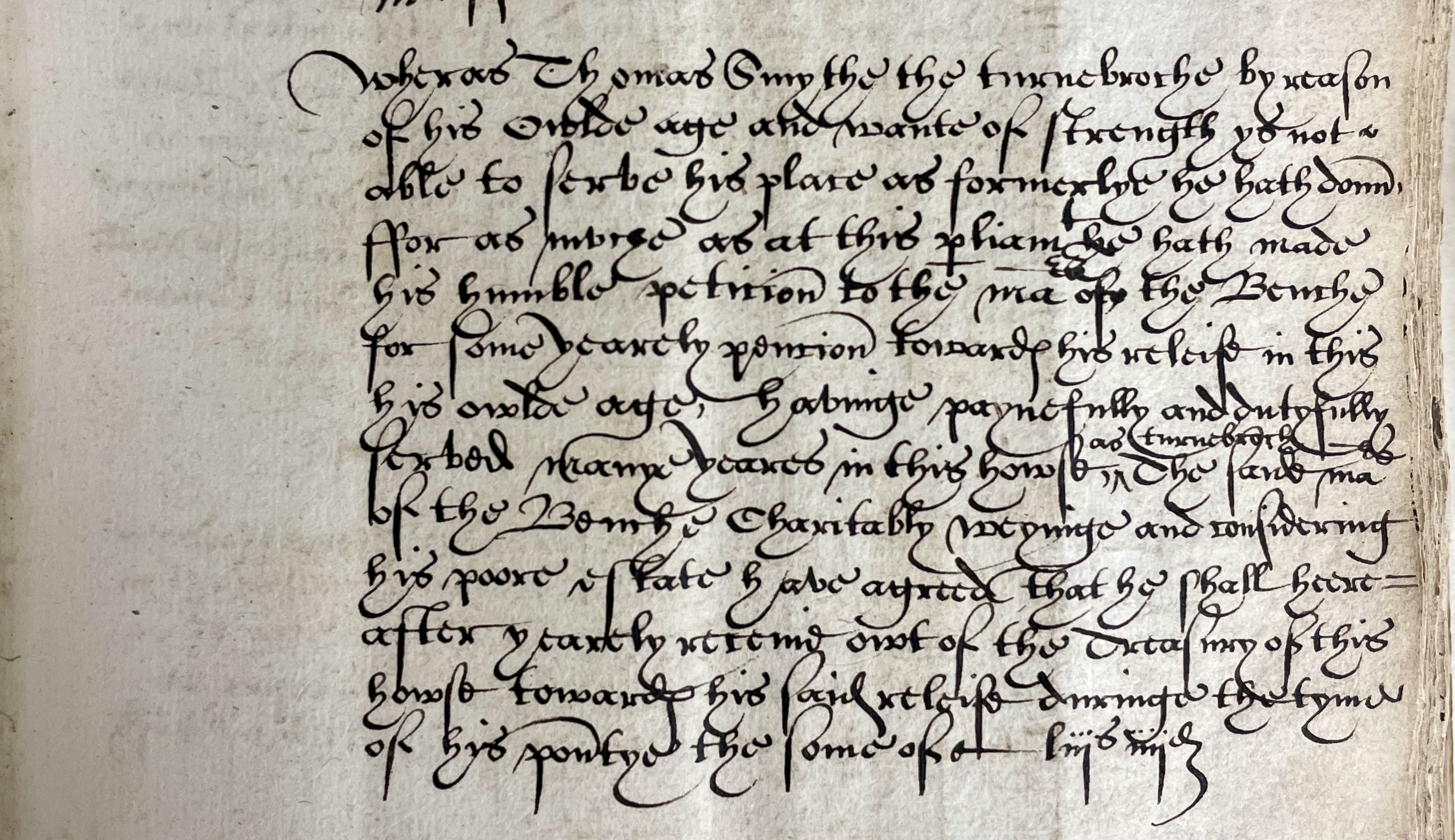

The Inn’s effort in resolving staff grievances might not always be documented, but it did show some care for its long-serving staff by providing ongoing financial support as they went into retirement. One early piece of written evidence of this was in 1602, when Thomas Smythe, Turnbroach (a kitchen servant turning the spike for roasting meat), asked for ‘some yearely pension towards his relief’ as he was unable to serve anymore due to his old age and lack of strength – he was granted 53s 4d. Another staff, William Burford, Panierman from 1645 to 1659, was given a pension of £5 yearly at the age of 78, later increased to £10, with other allowances over the years including further gratuities, twenty nobles (gold coins) and ‘a chaldron of coal’.

Order of Parliament granting a yearly pension to Thomas Smythe, Turnbroach, 29 October 1602 (MT/1/MPA/1)

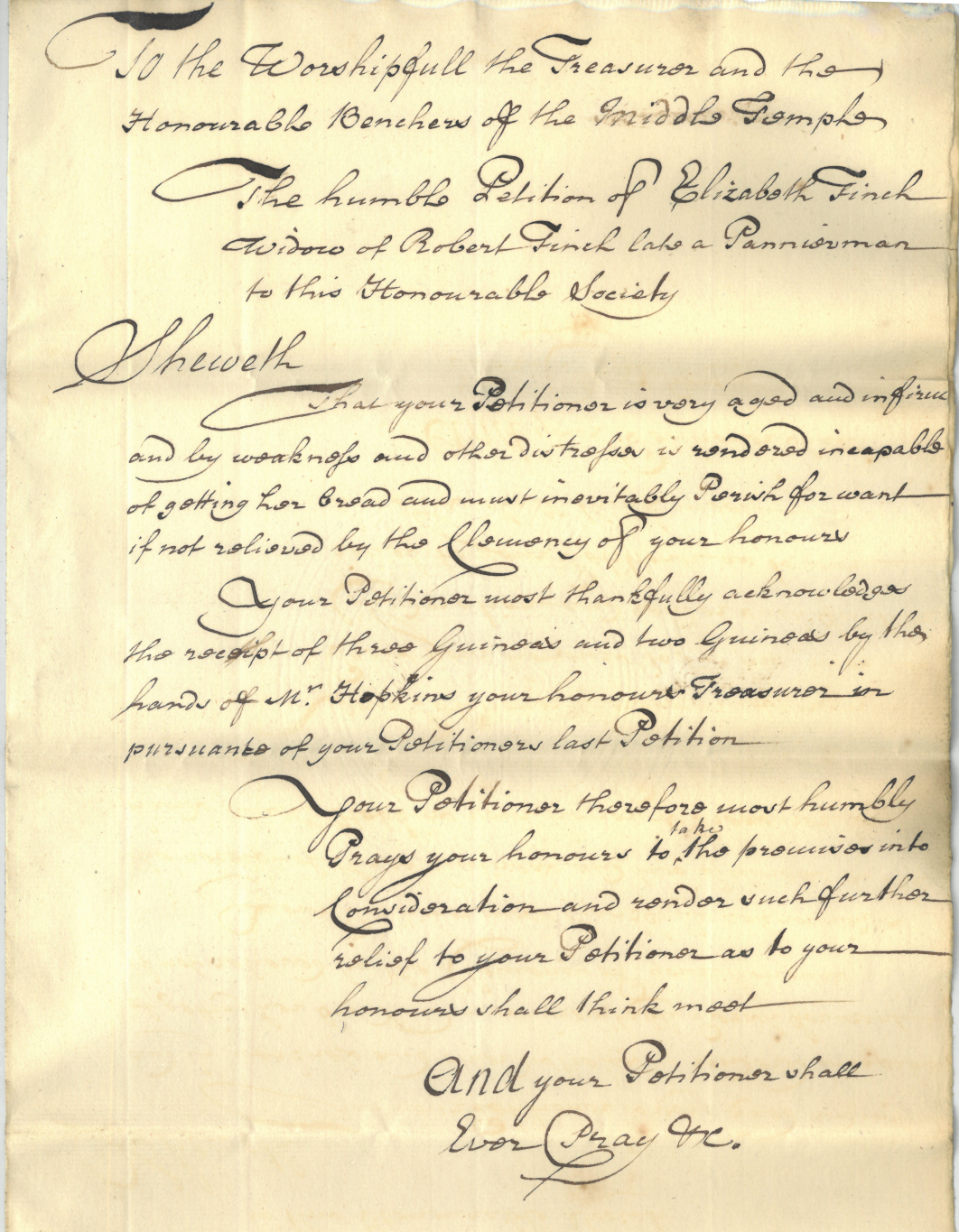

As an employer, the Inn’s benevolence in many cases extended to the families of staff, particularly when the death of an employee had left them in great hardship. One beneficiary whose situation was documented extensively in the minutes of Parliament during this period was Elizabeth Finch, widow of Robert Finch, Panierman and Watchmen. In 1756, Elizabath Finch was forgiven her arrears of three years’ rent amounting to £12. In subsequent years, she was granted a charity of £2 in 1758, followed by £3 in 1759, and then half a crown a week in the same year – this was later raised to five shillings a week in 1762 after she petitioned again, explaining that her chronic paralytic disorder rendered her uncapable of working. Elizabeth Finch died not long after submitting her last petition, having outlived her husband for almost three decades, and was buried in the Temple Churchyard in January 1764.

Petition of Elizabeth Finch, acknowledging money received from the Treasurer and pleading for further relief, 1759 (MT/21/1/1)

The Inn continues to be an employer to this date. In the later centuries, more policies and systems were to be put in place regarding employment conditions, often based on recommendations from dedicated committees. While conventions and expectations around employment have certainly changed, one thing that we can gladly agree on is that the working conditions at Middle Temple have seen much improvement since the early days.