The buildings of Middle Temple are an eclectic mix of different ages and architectural styles, reflecting a long history of construction and reconstruction stretching several centuries. One of the most recent waves of rebuilding took place in the years following the Second World War, in which many bombed buildings were demolished and rebuilt or replaced. This month, we look back on a dynamic decade marked by architectural vision and successive redevelopment works, tracing how the postwar reconstruction has shaped the appearance of the Inn today.

The postwar reconstruction was a monumental undertaking in many ways, as a result of the extensive damage caused during the Blitz. A full list of damaged buildings, with day-by-day details, can be found in Middle Temple Ordeal, a Middle Templar’s account of the lived experience of many Middle Temple members, residents and staff during the war. Significant damage was inflicted on the east end of Hall, Plowden Buildings, the Victorian Library, Lamb Building, Cloisters as well as buildings in Elm Court, Pump Court, Brick Court and more. After the war, over one-third of the Inn’s 285 sets of chambers had to be demolished, and ten others were rendered completely unusable.

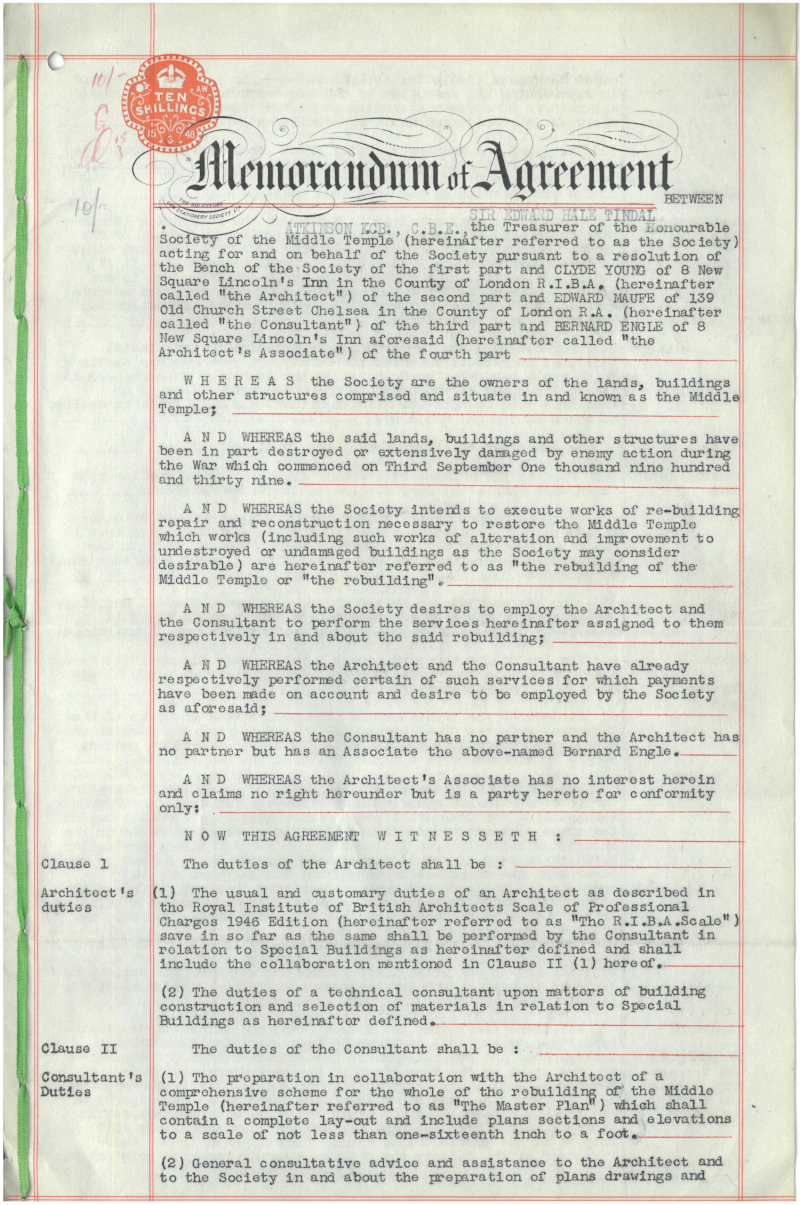

Bomb damage on Middle Temple Lane, c. 1941 (MT/19/PHO/10/11/20)

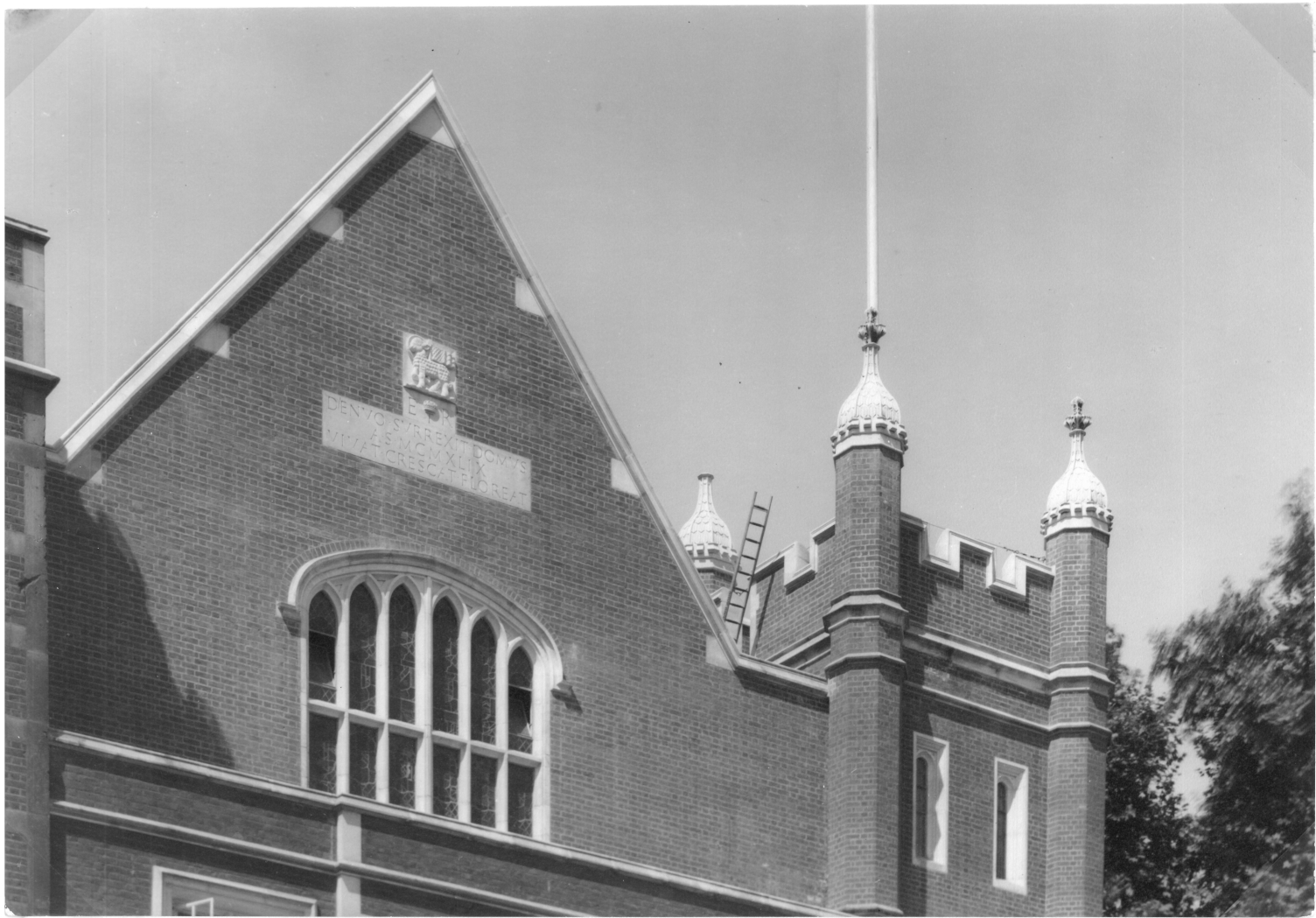

To recover from the calamity of war, reconstruction planning began as early as in July 1943, but it was not until December 1946 that Parliament empowered the Reconstruction Committee to oversee all matters relating to the rebuilding of the Inn. A key figure engaged by the Inn to assist with the Committee’s work was Sir Edward Maufe, the architect who designed Guildford Cathedral and many postwar memorials. First hired as a consultant in 1946, Maufe would go on to develop a blueprint for rebuilding the Inn in the 1950s.

Extract of agreement between the Inn and the architect and consultant regarding reconstruction, March 1948 (MT/6/RBW/297)

Priority for reconstruction was, for obvious reasons, given to Hall, being the heart of the Inn and its educational and collegiate activities. In 1946 Maufe drew up a scheme to restore Hall to its former glory, which involved repairs to or rebuilding of the east end, cupola, roof, entrance tower and clock. Among these, a notable achievement was the faithful reconstruction of the centuries-old screen, partly enabled by the painstaking efforts of C. G. Swanson, the Inn’s surveyor, and a group of volunteers who salvaged the smashed pieces of timber after the damage. Additionally, the reconstruction also provided an opportunity for the Inn to improve Hall’s ventilation, internal lighting and, subsequently, heating efficiency.

Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) standing in front of the restored Hall screen, accompanied by Masters Carpmael, MacGeagh and Craig Henderson on a private visit to inspect building work in progress, March 1949 (MT/19/PHO/1/2/2)

Another improvement which often goes unnoticed, this time more aesthetic than strictly functional, was made to the weathervane atop the roof. A more elaborate instrument, featuring the Inn’s lamb and flag emblem, replaced what Maufe described as a ‘miserable little unworthy thing’ in a letter to Master Kenneth Carpmael, member of the Reconstruction Committee. As a final touch to the reconstruction of Hall, Maufe also generously gifted to the Inn an octagonal lantern to replace the one hanging in the vestibule of Hall and destroyed during the bombing, having noted the unsatisfactory heraldry and glazing in the original replacement.

The octagonal lantern, showing the panels representing, from the left, Edward VII, the Knights Templar and Sir Francis Drake

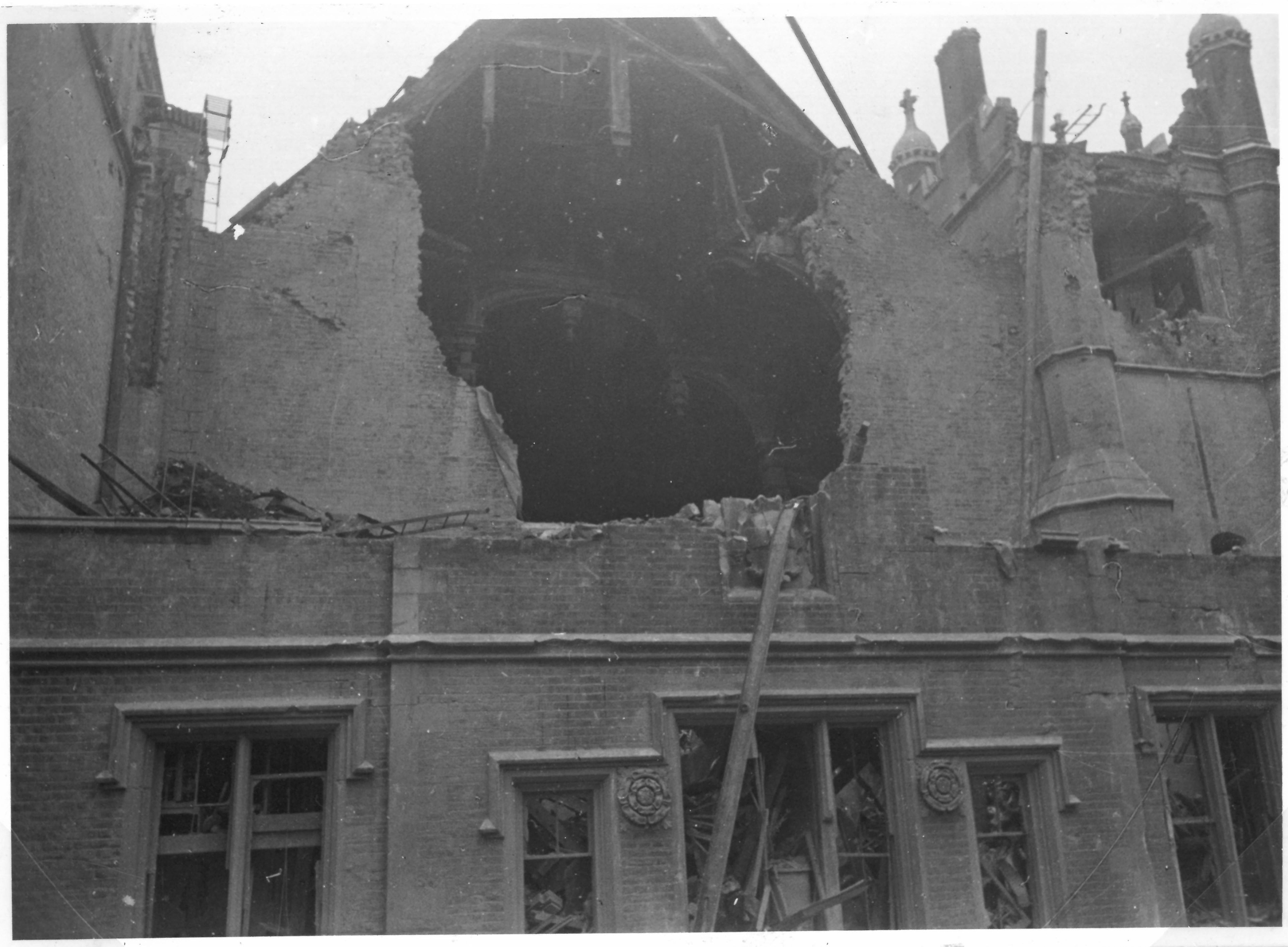

The restored Hall finally reopened in July 1949, an occasion graced by Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother), the Inn’s Royal Bencher and Treasurer of the year. This was commemorated with an inscription adorning the exterior of Hall that could still be seen today, celebrating that Domus rose again to live, grow and flourish.

Damage to the east end of Hall, exposing the double hammerbeam roof inside, taken in October 1940 (MT/19/PHO/4/1/4)

The east end of Hall, repaired, with a new inscription, taken in July 1946 (MT/19/PHO/4/1/13)

Not far from Hall, a temporary library, designed by Swanson, was erected on the sites of 2 and 3 Brick Court in 1946 to meet the needs of the Inn’s members. Although constructed using salvaged materials from damaged or demolished buildings and intended for short-term use, the single-storey structure provided enough shelving for around 50,000 books in its basement store, with basic amenities such as a common room and toilet. Having served a good twelve years, the library was demolished in 1958 to make way for parking spaces for cars.

The bungalow-style temporary library situated at 2 and 3 Brick Court, November 1946 (MT/9/LIB/71)

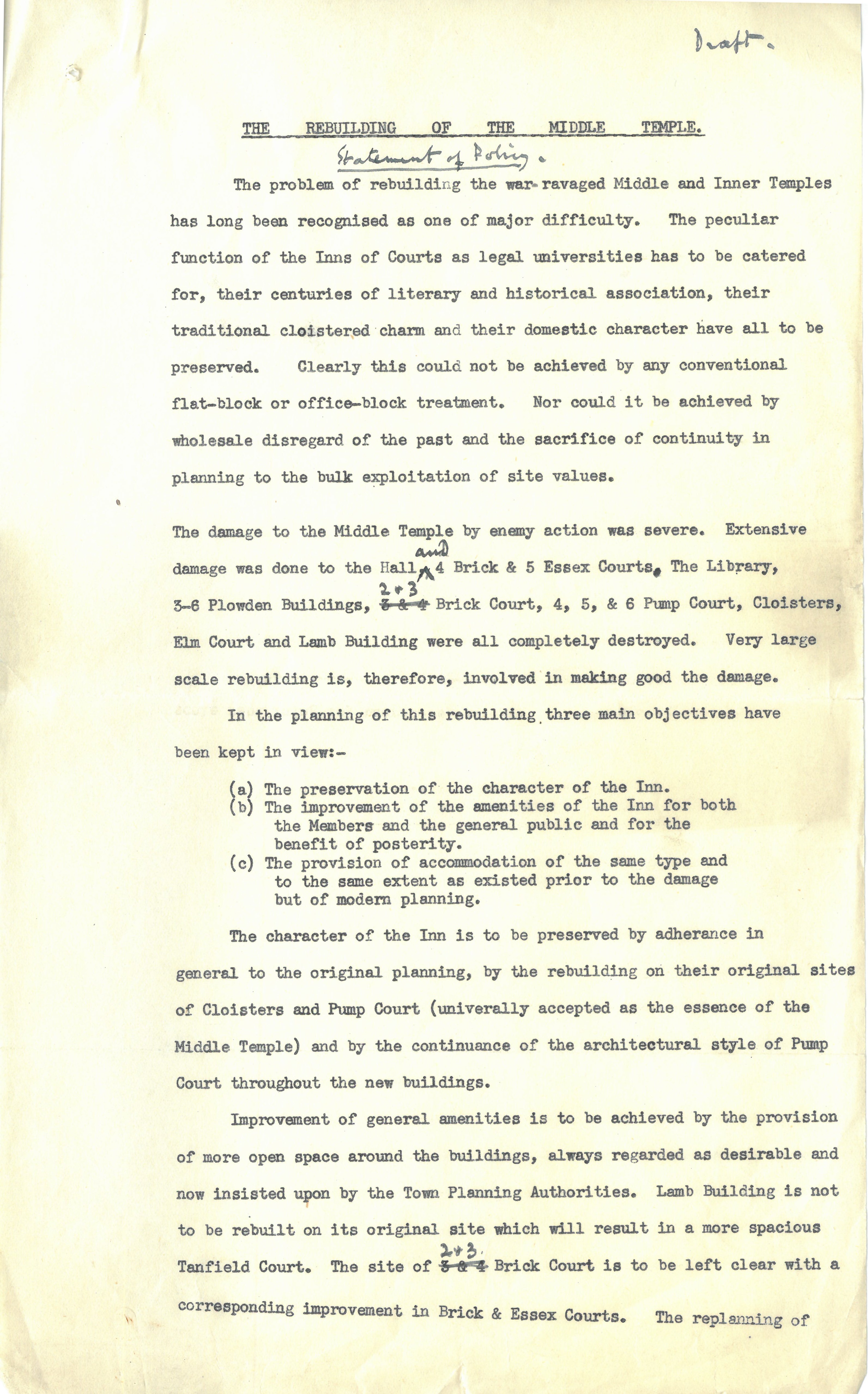

But the reconstruction of the Inn encompassed much more than the restoration of Hall and provision of a temporary library space. Maufe, now appointed the sole architect of the project, identified three main objectives of the rebuilding plan in a statement in 1950, one of which being ‘the improvement of the amenities of the Inn for both the members and the general public and for the benefit of posterity’. This might explain why, in many instances, the Inn did not intend to simply restore or rebuild buildings to their original size, layout or even location, but instead considered alternative schemes to make potential improvements.

Extract of Sir Edward Maufe’s draft statement of policy regarding the rebuilding of Middle Temple, June 1950 (MT/6/RBW/312)

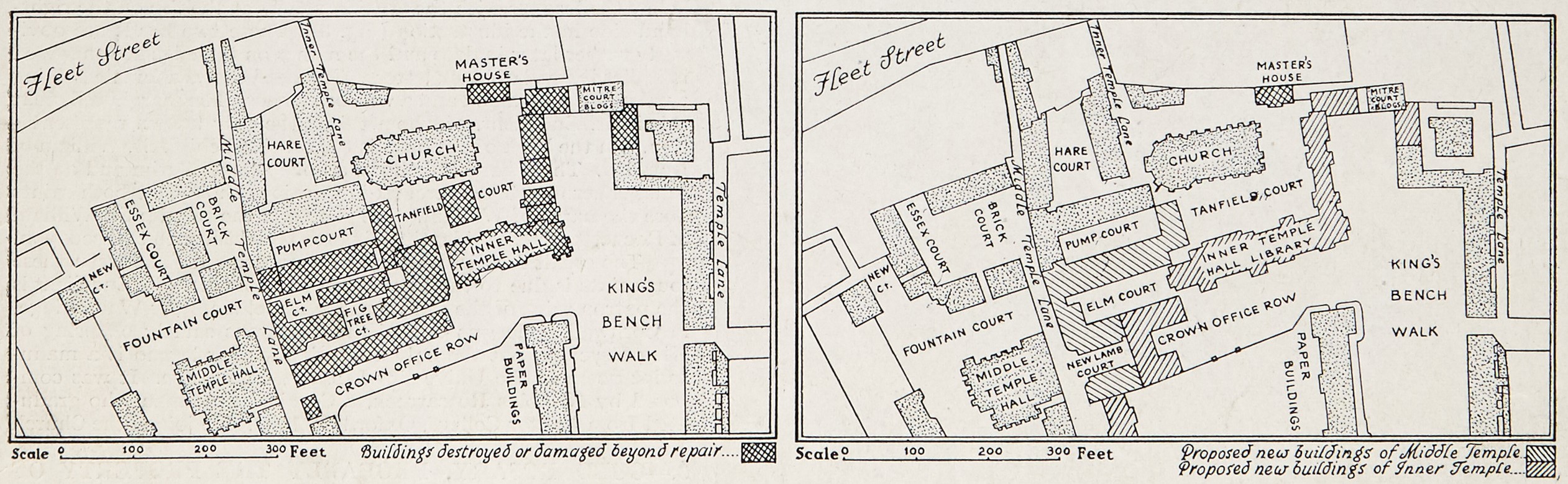

One major example of this can be seen in the area between the east side of Middle Temple Lane and Inner Temple Hall, where the courtyards and passageways were confined and narrow. To realise Maufe’s objective and comply with the Town Planning authority’s requirement, reconstruction was planned with the goal of providing more open space around these buildings. This would result in the loss of Fig Tree Court, incorporated into a more spacious Elm Court. What was then known as Tanfield Court, between Temple Church and Inner Temple Hall, would also be enlarged, made possible by the planned relocation of Lamb Building from the middle of the court to the south side of Elm Court.

Illustrated plans showing the damaged buildings (left) and an early version of the proposed rebuilding plan (right), May 1948 (MT/19/ILL/D/D8/26)

As the rebuilding plan involved property in close proximity to Inner Temple, part of the role of the Reconstruction Committee was to negotiate with them on where the new buildings of the two Inns should meet, as well as on any land exchange necessitated by the reconstruction. In February 1952, a revised master plan, jointly developed by their respective architects, was finally agreed upon. This plan delineates the new boundary of both Inns’ property, and would establish the layout of Temple with which we are familiar today.

Revised master plan co-produced by Sir Edward Maufe, architect to Middle Temple, and Sir Hubert Worthington, architect to Inner Temple, 1952 (MT/6/RBW/312)

Reconstruction works were in full swing once the master plan had been confirmed. By the end of 1952 the first reconstructed building, Cloisters, was completed, followed by 1–4 Pump Court, in early 1953. At the time of completion, these together provided 30 sets of residential and business chambers, each supplied with central heating and constant hot water. A slight difference in the design of the new Cloisters is its reduced number of arches, featuring one fewer than its original eight – a decision to revert to an early design by its architect, Sir Christopher Wren.

Craftsman working on the arcade of Cloisters, 1952 (MT/19/10/1/31)

Extract of an aerial photo of Middle Temple, showing the temporary library in Brick Court, the remnants of the Victorian Library and 3–6 Plowden Buildings as well as buildings under construction around Elm Court, 1952 (MT/19/PHO/14/6)

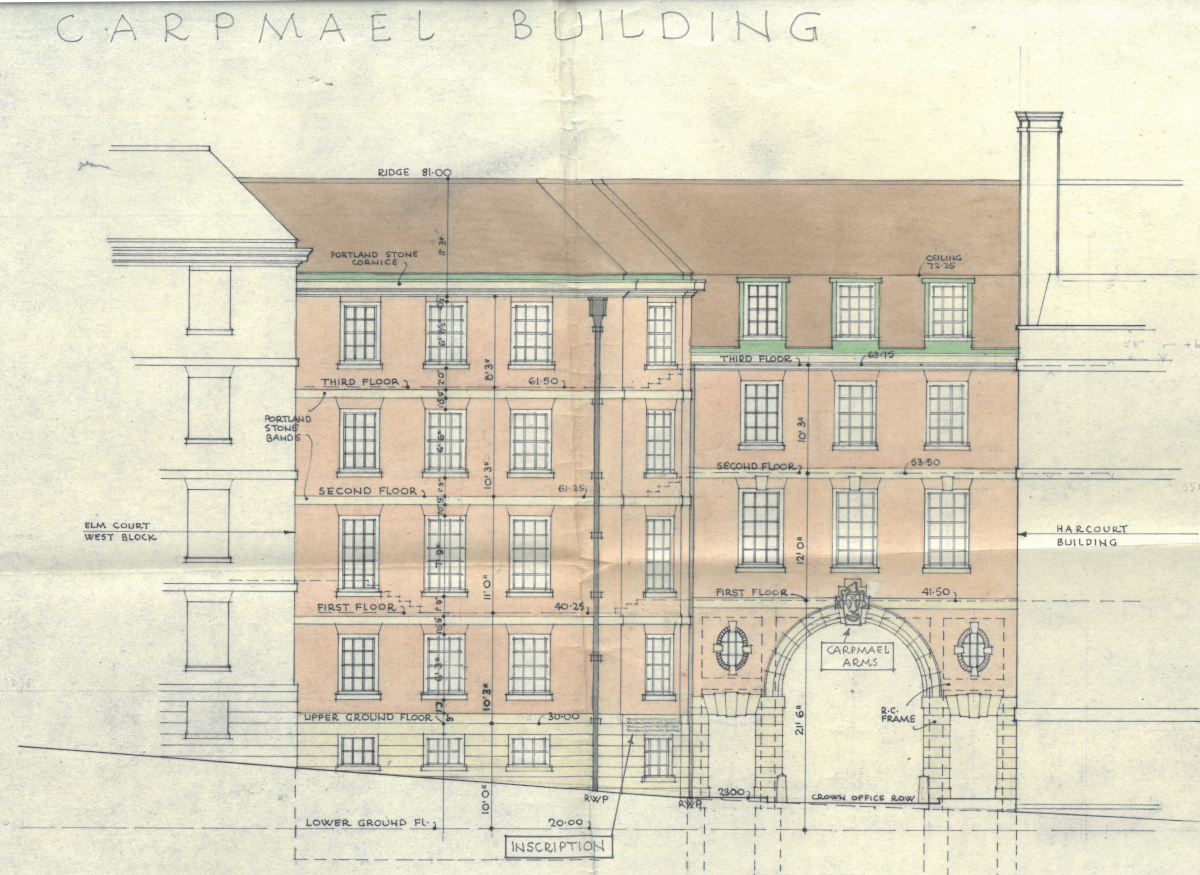

The next two years would see the completion of the relocated Lamb Building (1954) and another new building (1955), replacing the western end of Crown Office Row buildings. This incorporated a wider arch, enabling easier and segregated traffic and pedestrian access to Middle Temple Lane and maximising the space above for additional chambers. The new building was named after Master Carpmael, who became the first Master of the House in 1950, Lent Reader in 1954 and Treasurer in 1961, in honour of his ‘signal service’ to the reconstruction.

Coloured plan of Carpmael Building, showing the position of Master Carpmael’s arms and an inscription commemorating his contribution to reconstruction, [1955] (MT/6/RBW/316)

On the site of the demolished Victorian Library, a new building dedicated to the Queen Mother, named the Queen Elizabeth Building, was erected. It was first envisioned to be a two-staircase building, but due to subsequent consideration to the Inn’s financial position, one floor was scrapped and a single-staircase scheme was adopted, housing 10 sets of residential and business chambers. Bearing the arms of the Queen Mother and Queen Elizabeth II on the pediments, the building was opened in November 1957 by the Queen Mother, who was said to be much impressed by the design of the chambers.

Letter from Clarence House to the Inn expressing the Queen Mother’s satisfaction following her visit for the opening of the Queen Elizabeth Building, November 1957 (MT/6/RBW/318)

The last building to be completed in the grand reconstruction scheme was the Inn’s new Library, later renamed as the Ashley Building, which opened in November 1958. Immediately following the war, rebuilding the Library on its old site had been considered as an option, with Maufe producing a detailed ground plan for a six-story structure. However, Parliament later resolved that a new Library in ‘en suite’ style with the Bench Apartments and Hall would serve the best interest of its members. The postwar library building would go on to become the centre of the Inn’s administration and education activities, today housing the Treasury Offices, encompassing many departments, and an advocacy suite. With hindsight, the decision of providing the Inn’s staff and members direct and convenient access to the Bench Apartments and Hall proved to be shrewd.

Entrance to Middle Temple Library, showing the coats of arms of the three Treasurers involved in the building of the new library, 1958 (MT/19/PHO/5/19/6)

In February 1959, as the reconstruction work drew to a close, Parliament passed a motion to express their deep sense of gratitude to members of the Reconstruction Committee, to whom they owe ‘the wonderful restoration of Domus’. Through reconstruction the Inn regained its vigour and found new impetus to go forward, while Middle Templars could once again build and develop their professional lives, now in an environment more suited to their needs. The influence of this has certainly not lost to time, not least because of the architectural beauty and uniqueness that are one of the distinguishing features of the present Inn, to which we owe much to the labour and foresight from many decades ago.