As we move into 2025, the Middle Temple is looking forward to the events and occasions to come – many of which will of course be documented in the Archive. So, to begin the year, this month we look back at the years ending in ‘25’ from the past four centuries, exploring the many remarkable events both within the Inn and in the world outside which impacted upon the lives of our members.

1625

The year 1625 began with reports at a Parliament in February of members having had a rather raucous Christmas period, with later records announcing that an enquiry would be launched into the disorder that had occurred. There was certainly no repeat of this behaviour during the summer of that year, as London and the Inn were struck with plague. The minutes of a Parliament held in July state that “there shall be no Summer reading this year, by reason of the great increase and danger of the sickness […] all shall depart out of the House”.

1625 was a year of royal change, with Charles I ascending the throne as King. Charles was the second son of King James VI and I, under whom, in 1608, the land of the Temple was at long last conveyed into the hands of the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple by Letters Patent. A large portrait of Charles I, believed to be painted by Sir Peter Lely after Van Dyck, was purchased by the Inn in 1684 and has hung in Hall since its acquisition.

Portrait of King Charles I.

In 1625, Garden Building, now known as Garden Court, was erected at the Inn. This building took on particular importance for the Inn some years later as, following the 1641 bequest to the Inn by Robert Ashley of around 6,000 books, the collection was eventually moved here and the building became the Inn's Library.

Photo of Garden Court, c. 2018 [MT/19/PHO/14/13].

1725

By the 1700s, the Inn was no longer the vibrant hub of legal, social and political life that it had once been. It was, however, still an eventful period with occurrences of note taking place throughout 1725.

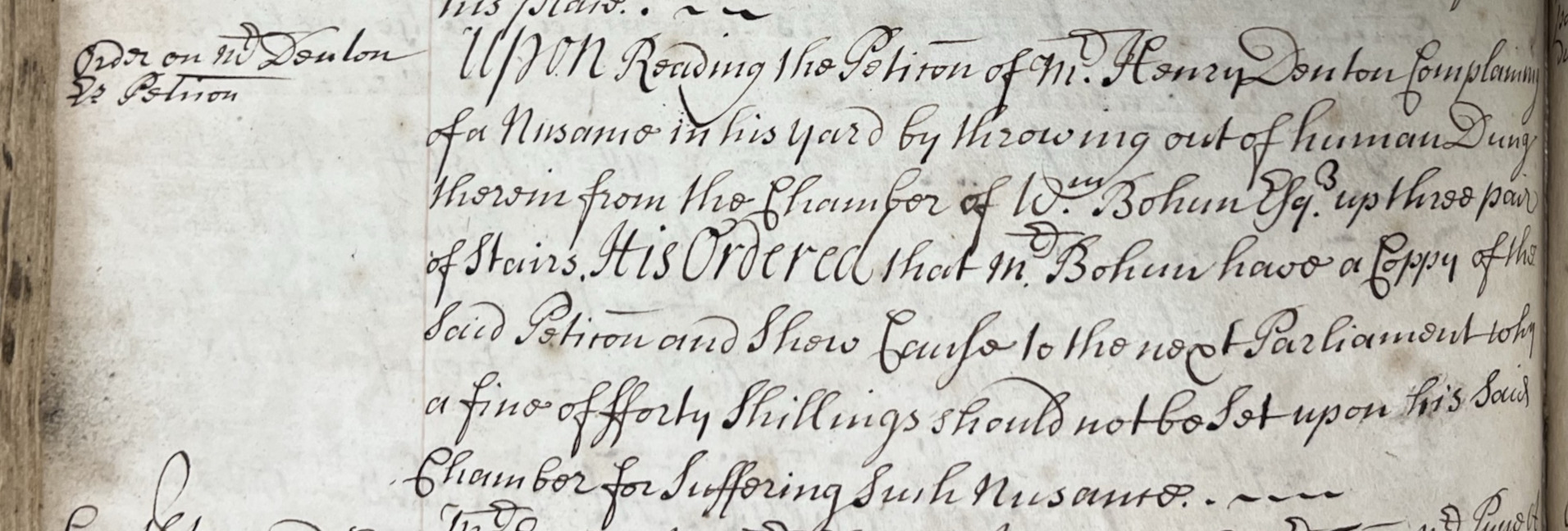

One had to be careful when walking around the Inn at this time. In 1725, a petition came to the Inn’s Parliament from one Henry Denton, complaining of a nuisance in his yard caused by the “throwing out of human dung therein from the Chamber of Mr. Bohun”. The Inn stated that Bohun was required to show cause to the next Parliament “as to why a fine of 40 shillings should not be set upon his Chamber”. However, due to Denton not attending the next Parliament to follow up on his allegations, the petition was dismissed and Bohun cleared.

Denton's petiton being noted at the Inn's Parliament, 1725 [Middle Temple Minutes of Parliament].

For a period from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth century, the Inns of Court were among the most popular places in London for abandoning children who, for whatever reason, could not be cared for. On 26 November 1725, there is a record of the Inn having a conference with Inner Temple to discuss the right of the ground in Fig Tree Court at the entrance of the passage leading into Elm Court, where a female child was dropped the previous Saturday, and thus which Inn should be responsible for her care. It was concluded that it was owned by Middle Temple, and the child was consequently taken into the care of the Inn.

Fig Tree Court, 1930 [MT/19/ILL/E/E3/3].

In 1725, Thomas Sherlock, who had been appointed Master of the Temple in 1704, was gifted a silver-gilt cup by the Benchers of the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple. The Sherlock Cup (as it became known) was made by Samuel Jefferys and bears the Lamb and Flag, the Pegasus and the coat of arms of Thomas Sherlock. The cup was passed through the Sherlock family line, but, when the lineage ended in the 1990s, it was bought jointly by the two Inns and is now held by each Inn in alternate years.

The Sherlock Cup.

1825

In 1825, the diary of Samuel Pepys was published for the first time, bringing to light an insightful and entertaining view of London life in the mid-1600s. The diary makes references to the Middle Temple, including a reference to Candlemas in 1663 – Pepys records meeting with one Madam Turner who had ‘been at the play to-day at the Temple, it being a revelling time with them’. This diary, and others such as John Evelyn’s, enable us to expand and enrich our understanding of the social history of the Inn.

Samuel Pepys. [MT/19/POR/538].

The 1820s saw substantial development and reconstruction work at the Inn. The two Bench Apartments on the south side of Hall had recently been completed and opened for use by Masters of the Bench. Both rooms originally had different purposes to their current functions: The present-day Parliament Chamber was used as the Inn’s library until 1861, and what is now the Queen’s Room was itself originally the Parliament Chamber.

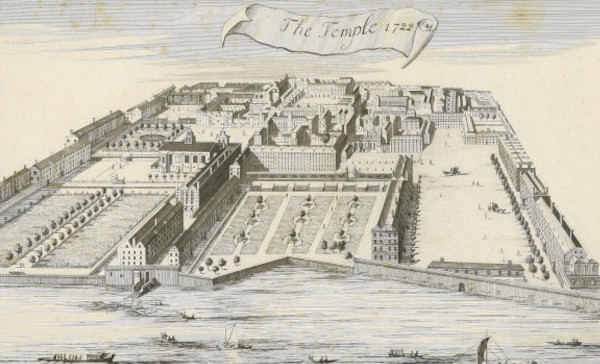

With the introduction of these new rooms, the Benchers sought to improve their view down to the River Thames, which would have involved cutting down the lime-tree avenues of the Inn’s Garden. There was uproar in response to this proposal, with the Sussex Advertiser calling it a “tasteless act of modern Vandalism”. The plan was quashed by Parliament on 11 November 1825, due to the strength of opposition from the membership, although the trees would not in fact survive to the middle of the century.

The Temple, 1722, showing the lime tree avenue of the garden [MT/19/ILL/D/D8/29].

This year also saw the Temple Church take its first steps towards a real restoration, having only been subject to general repairs in 1811. In 1825, Robert Smirke was employed by the Inn to restore the whole external south side of the Church and the lower part of the circular portion of the Church Round.

Temple Church, as restored, 1828 [MT/19/ILL/C/C3/13B].

1925

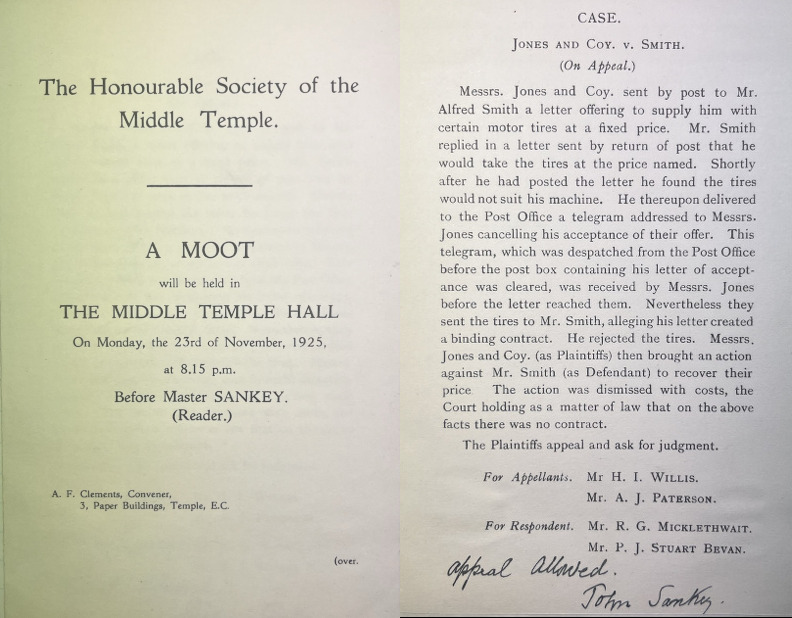

In 1925, John Astbury was appointed as Treasurer of the Inn. During this year, Astbury oversaw the return of the Inn’s first regular moots in more than a century, held after dinner in Hall on 23 November 1925 and attracting, in the Law Times’ words, ‘a large attendance’. The case mooted concerned a dispute over the alleged breaching of a sales contract for motor tyres.

Moot Programme from 26 November 1925 [MT/13/MOO/3].

Not only did this year see the return of mooting to help students in their preparations for the Bar, but also the establishment of the Harmsworth Scholarships and their first awards. Inspired by this, Master Astbury, who had helped prepare the Harmsworth scheme and assisted in selecting scholars, wrote in his will that any remaining funds, after his family had been supported, should be donated to the Inn to establish a scholarship on almost identical lines with those founded by Lord Rothermere.

In 1935, after Astbury’s death, his generous bequest was granted to the Inn. As the trusts were so alike, the Harmsworth and Astbury Scholarships came to be administered by a single committee with candidates interviewed on the same day and a single list of awards made. Students are still awarded this scholarship today.

Stained Glass Window of Master Astbury.

It was also in 1925 that the Inn decided to ensure that its historical records were kept in good order and safe hands. Many years later, in 1990, the Inn employed a qualified archivist for the first time, to ensure the access and conservation of the records, with a purpose built-archive repository for the records being opened in 2007.

Middle Temple Archive Repository, 2020.

2025

As 2025 begins, we look forward to an exciting calendar of educational and social occasions, and it will without doubt be a rich and memorable year – and perhaps one which will be looked back upon and written about in 2125, 2225 and beyond.