International students have been a distinguished part of the Inn’s membership for centuries. This month, we focus on one group with a particularly strong presence in the Inn’s modern history – members from the Indian subcontinent. A presence in the Inn since the mid-19th century, Indian members have contributed to the diversity of the Inn and advocated for changes in educational and institutional rules. We highlight certain eminent figures in modern Indian history to have been educated at the Inn and also explore the individual experiences of student members.

Beginning in the 1860s, following the establishment of the three High Courts in India by the British government, the Inns of Court saw an influx of Indian students seeking to be Called to the Bar and thus obtain the qualification to plead in their home courts. In addition to these future barristers, individuals applying to or serving in the judiciary of the newly founded Indian Civil Service, now the main executive arm of the British Raj, were also drawn to the legal training offered by the Inns of Court.

Calcutta High Court, c. 1872 (From the British Library archive, Photo 179 no 2)

In the dawn of India’s judicial and administrative transformations, many aspiring young men of the region decided to pursue a legal education at the Middle Temple. After their studies, many returned home and played pivotal roles in Indian politics and legal affairs. Among them were at least three famous founding members and presidents of the Indian National Congress, the country’s oldest political party and a major force in the movement for Indian independence. These included Badruddin Tyabji (admitted 1863), Womesh Chunder Bonnerjee (admitted 1864) and Surendranath Banerjee (admitted 1869).

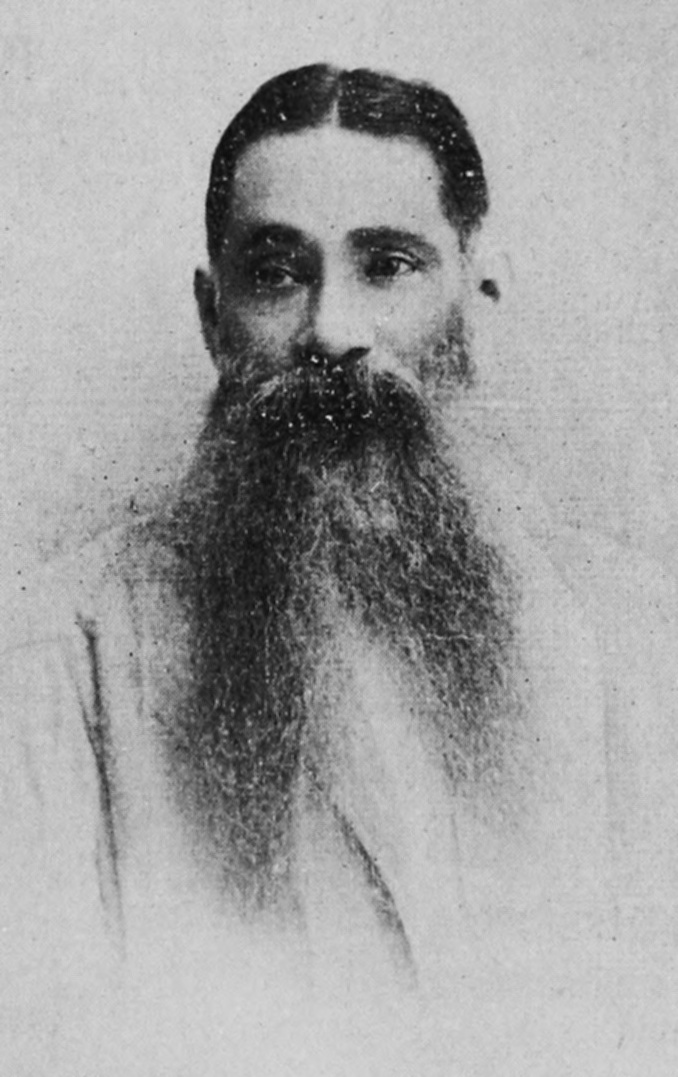

(From the left) Badruddin Tyabji, Womesh Chunder Bonnerjee and Surendranath Banerjee, three of the Inn’s early Indian members

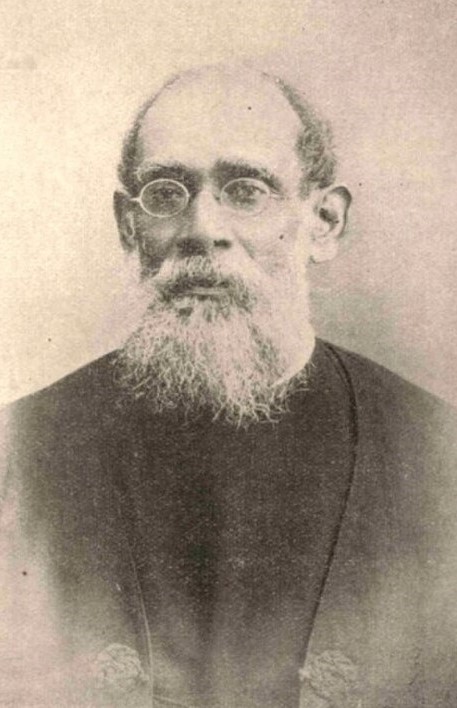

Another notable figure was Vallabhbhai Patel (admitted 1910), an independence activist who served as the first Deputy Prime Minister of India after its independence. One of Patel’s biographers described how this founding father of the Republic of India diligently spent his time at the Inn, standing ‘outside the door of the Library, waiting for it to be opened, and not end his reading till time was pronounced at 6pm’. Patel was undoubtedly a frequent visitor of the Middle Temple Library; his signature first appeared in the Library attendance register on 19th October 1910 – just a few days after his admission – and can be found throughout the volume.

Vallabhbhai Patel’s signature (No. 56) in the Library attendance register, October 1910 (MT/9/LAB/26)

Patel was Called to the Bar in January 1913, having passed the Bar Examination with first class and received a Certificate of Honour along with a prize of £50. In 2014, an event co-organised by the Indo-British Cultural Exchange was held at the Inn to celebrate the centenary of Patel’s Call. A plaque in the form of a miniature armorial panel – bearing Patel’s heraldic shield in resemblance to the Indian national flag – was presented to the Inn on the occasion.

A plaque celebrating the centenary of Vallabhbhai Patel’s Call to the Bar at Middle Temple, unveiled in 2014 (MT/19/PHO/6/54)

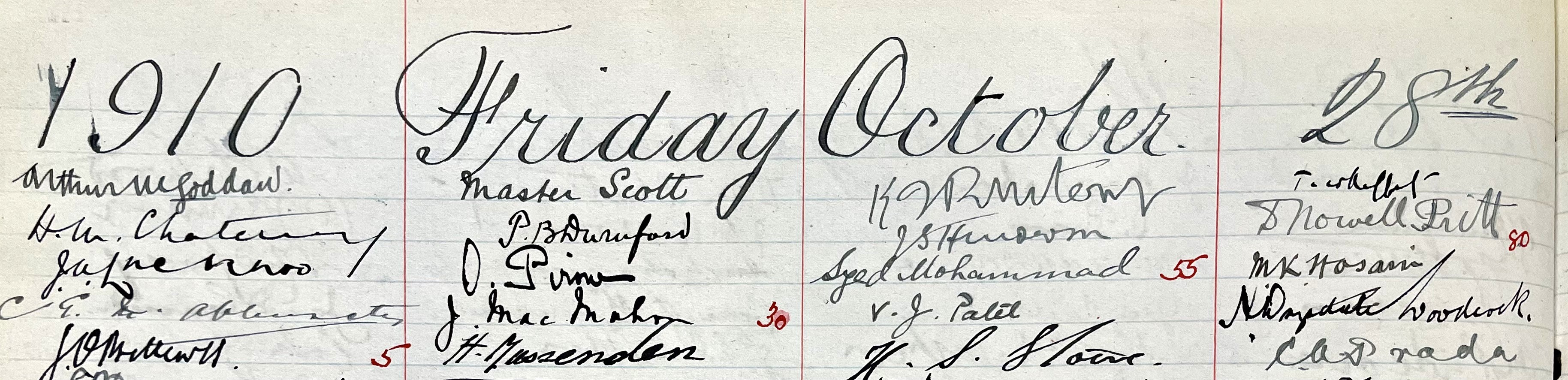

As well as those whose destiny lay in the political sphere, the Inn also provided legal education to some of the earliest Indian officers who qualified for the Indian Civil Service, at a time when composition of the service was predominately white British. The three Indian officers who joined the service in 1871 – Banerjee, Behari Lal Gupta and Romesh Chunder Dutt – were close friends, setting sail to England together, and all joined Middle Temple. Dutt rose to the rank of a divisional commissioner and was a prolific economic historian, while Gupta became the first Indian Chief Presidency Magistrate.

Romesh Chunder Dutt’s certificate for completion of pupillage, May 1871 (MT/13/CLA/7)

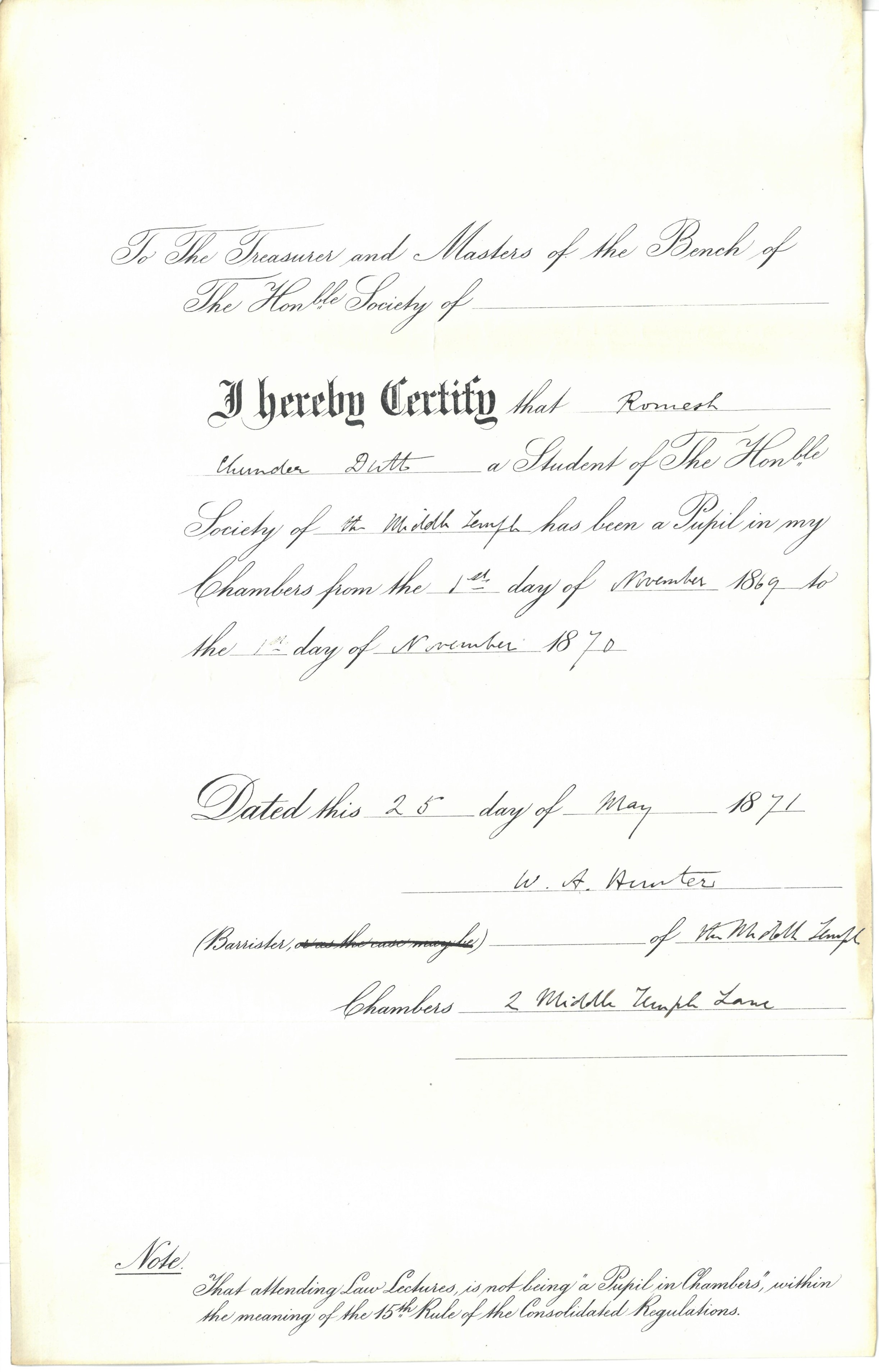

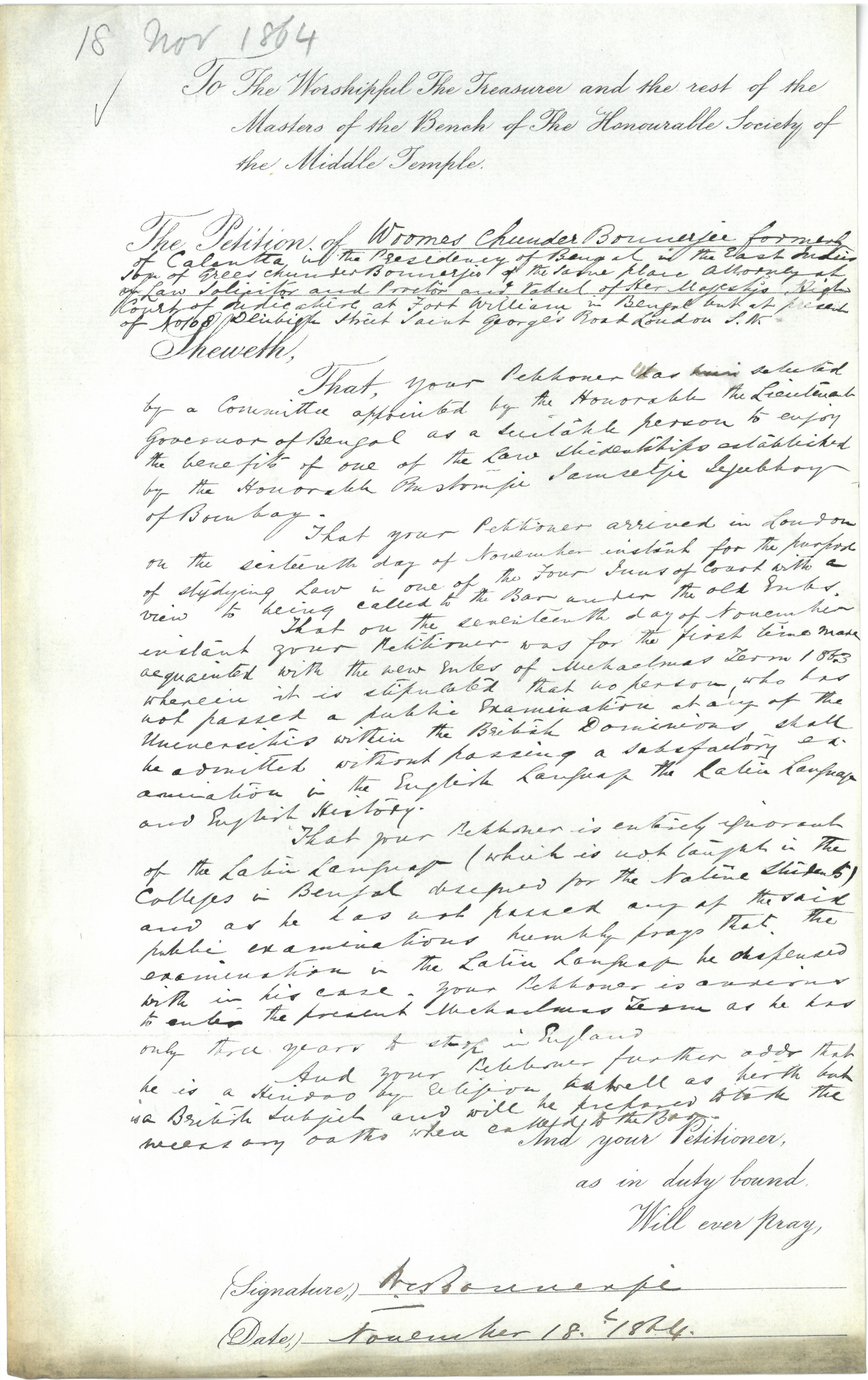

Certain academic challenges and difficulties could present themselves to Indian members – one obstacle being the admission requirement of having a satisfactory knowledge in Latin. Those who had not passed a university entrance examination were subject to this – including Bonnerjee, who in 1864 petitioned for dispensation. Admitting that he was ‘entirely ignorant of the Latin language’, he pledged that he would be prepared to take the necessary oath as a British subject when Called to the Bar, despite being Hindu by religion. Many similar petitions followed, and it was only in 1891 that the committees of four Inns of Court provided grounds for exception, that it was justifiable for native Indian students to apply for such dispensation.

Womesh Chunder Bonnerjee’s petition for exemption from the admission requirement regarding the Latin language, November 1864 (MT/21/1/12)

Once admitted, the academic journey of these Indian members was similar to that of their local counterparts. During this period, legal education at the Inns of Court was delivered in a more codified manner than previously. There were lectures dedicated to different areas of practice, followed by examinations on the subjects.

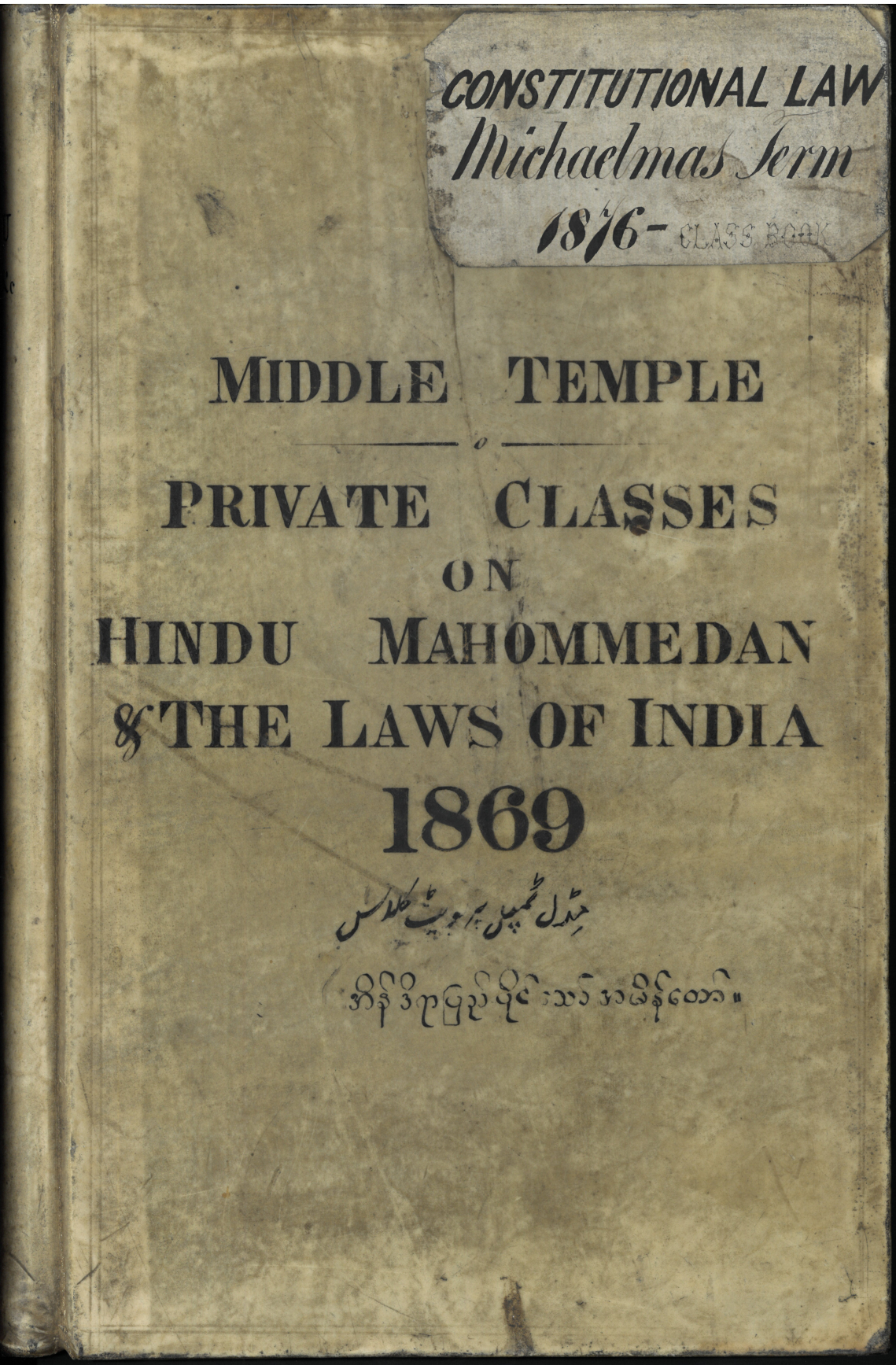

However, there were initially few opportunities for students to learn Indian law. In the late 1860s, a group of Inns of Court students submitted a memorial for the appointment of a lecturer of Indian law, backing up with the facts that ‘the number of Indian law students is increasing daily and many gentlemen of the English Bar leave this country annually to practice in India’. Dutt and Sir Taraknath Palit (admitted 1867), an educationist and philanthropist, were among the signatories. Responding to the growing call, the Council of Legal Education appointed a Reader in Michaelmas 1869 to give lectures and classes on Hindu and Mahommedan Law, as well as on the laws in force in British India, followed by regular examinations.

Cover of the attendance register of lectures on Hindu and Mahommedan Law and laws in India, 1869–1876 (MT/13/PPL/3/8)

But changes to educational schemes could lead to new grievances. The examination in Trinity 1871, for example, was notoriously difficult, and it was reported that none who sat for the examination passed. One student of the Inn, Robert Nisbet, felt compelled to write to the Inn after being ‘deeply mortified by this extraordinary result’. Despite having nearly ten years of experience as a judicial officer in the Indian government, Nisbet found no advantage in the examination – he attributed this to the sheer number of examination questions – over 130 – and found it ‘an utter physical impossibility’ to complete in the given three hours.

Robert Nisbet’s petition for being Called to the Bar on keeping only eight terms, June 1871 (MT/1/PPA)

It is easy to forget that more than a century ago travelling, studying or living abroad could be much more burdensome than now. Records in the Archive also show that the challenges facing early Indian members at Middle Temple sometimes went beyond the aspect of legal education and involved personal values and beliefs.

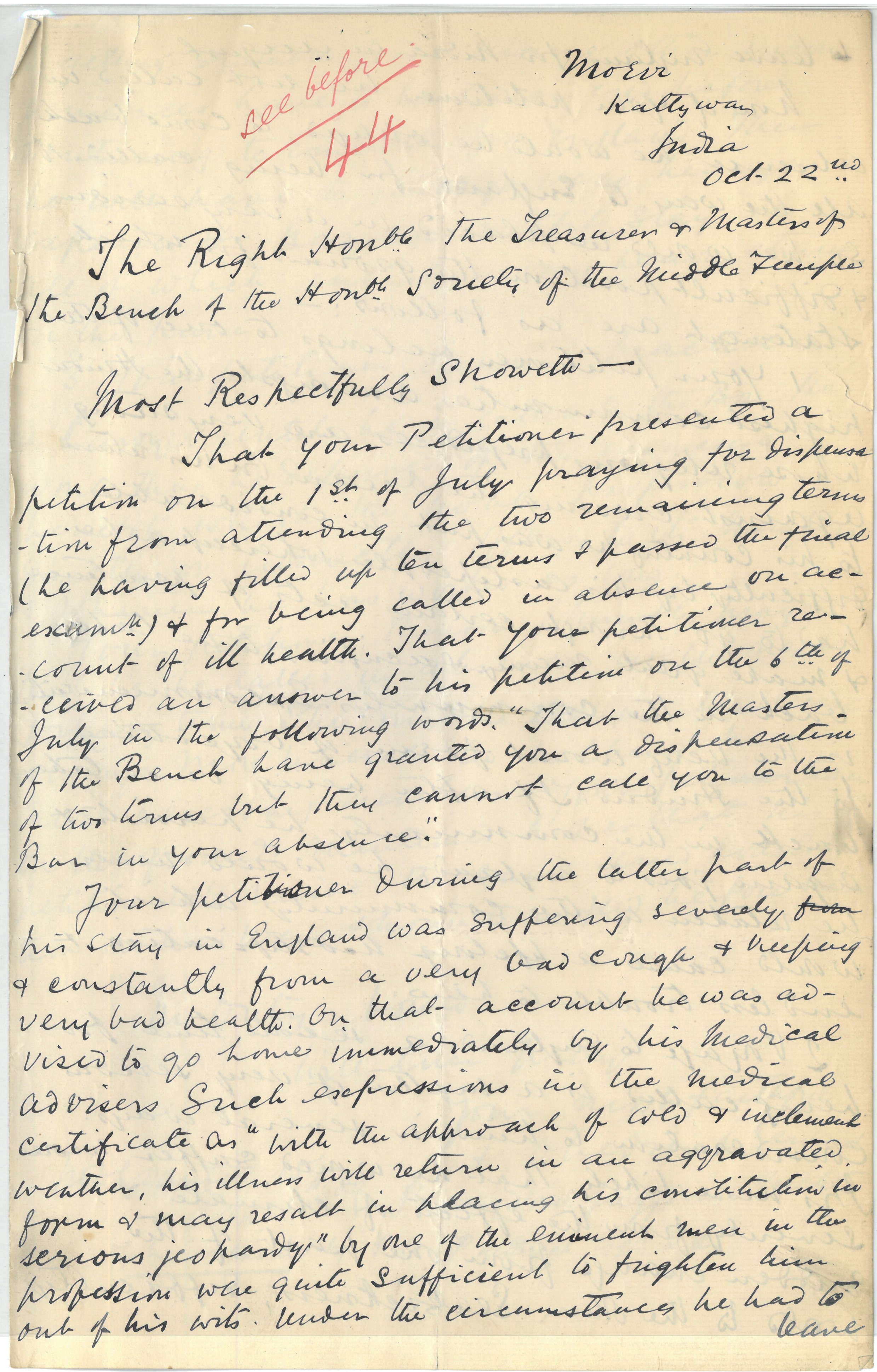

One example can be seen in the petition of Pranjivan Jagjivan Mehta (admitted 1887), who befriended Gandhi while in London and remained his lifelong supporter. Having suffered from bronchitis during his time in London, Mehta was concerned about seasickness, cold weather and the difficulty of getting suitable food if he had to travel back to England for his Call. But an even more catastrophic consequence might befall – he wrote that he would risk excommunication if he attempted to set sail again, as he belonged to a community whose religion strongly opposed crossing the ocean. ‘Excommunication is the very worst form of boycotting to the Hindu. If after being taken back in the community he persists and again goes to England he would never be retaken in the community.’

Extract of Pranjivan Jagjivan Mehta’s petition for being Called in absence, October 1889 (MT/1/PPE)

Mehta’s petition for being Called in absence was supported by Master Frederick Philbrick, Lent Reader 1887, who spoke empathetically about Mehta's ill health, saying that ‘no one could have seen him without feeling how terribly England had told on his chest and lungs’. This did not convince Parliament, who rejected Mehta’s petition. Mehta was eventually Called to the Bar in June 1890, after which he returned to India and practised as a physician.

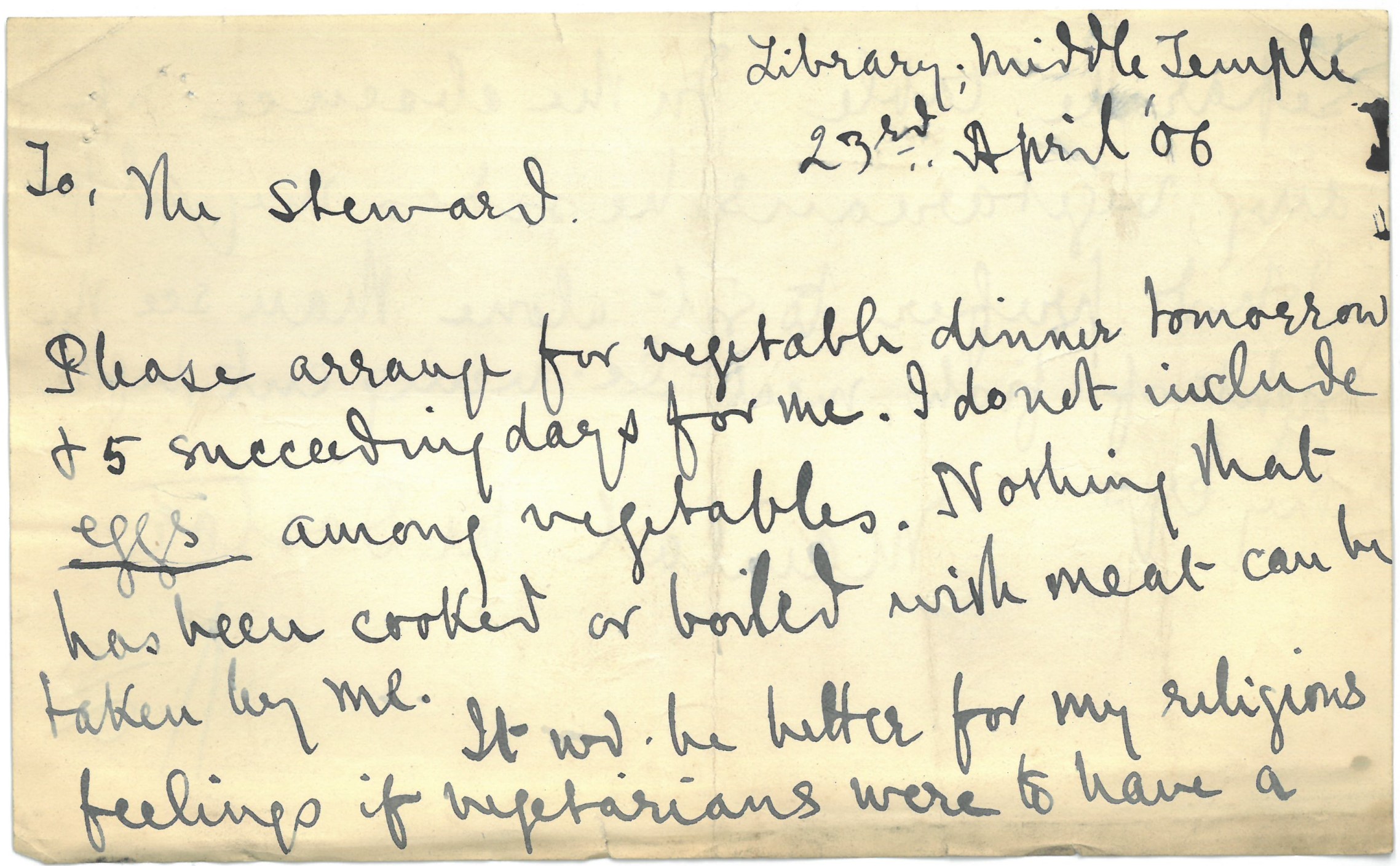

Religious tension sometimes manifested in ordinary places like the dining table. In 1906, a Manilal Maganlal Doctor wrote to the Steward of the Inn requesting vegetable dinners to be provided for him, which he said would be better for his ‘religious feelings’. Doctor stated that he would ‘prefer to sit alone than see the sight of fish, meat, etc. being cut before [his] eyes.’ Whether special arrangements were actually made is unknown, but there is evidence that dinner menus from around this period did include separate vegetarian sections, so Doctor’s request might not have seemed entirely impracticable.

Extract of Manilal Maganlal Doctor’s letter to the Steward requesting vegetable dinners, April 1906 (MT/21/1/23)

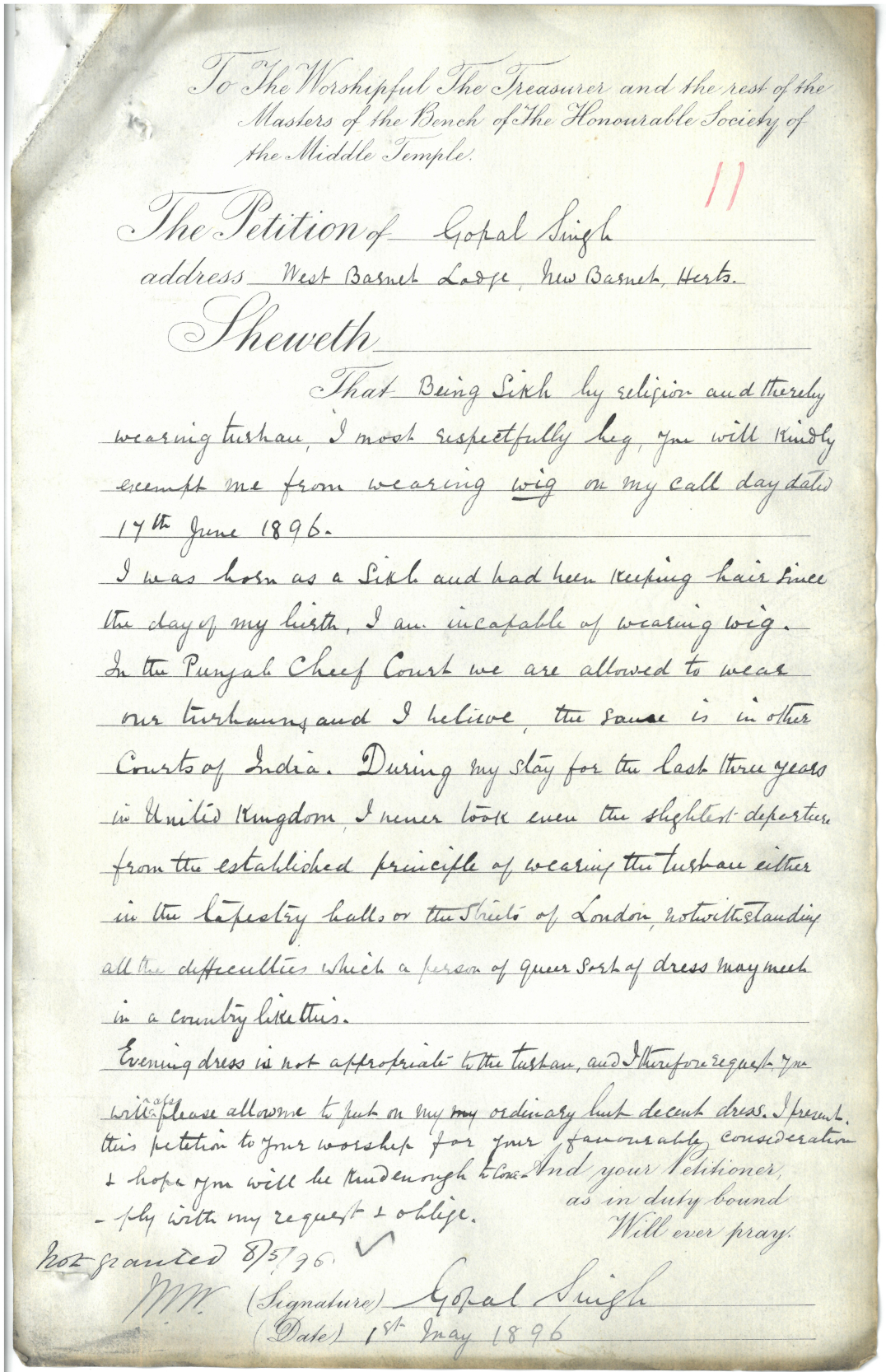

Doctor’s experience was shared by other Indian students with a strong attachment to their religion. In 1896, Gopal Singh, a Sikh student from Punjab, petitioned to be exempted from wearing a wig on his Call day so that he could maintain his turban, a religious headwear. Singh wrote about how he had faithfully adhered to wearing his turban during his three years with the Inn, from grand halls to the streets of London, despite ‘all the difficulties which a person of queer sort of dress may meet in a country like this’.

Gopal Singh’s petition for exemption from wearing a wig at the Call ceremony, May 1896 (MT/21/1/113)

The Inn, however, was not ready to bend the rules at this time and rejected Singh’s petition. Singh went to great lengths to defend his individual expressions of faith, declaring that it was ‘impossible to violate his religious principles’ and eventually withdrawing from the Inn. Twelve years later, however, in 1908, at the request of the India Office, the requirements were relaxed such that Sikh students could choose not to wear wigs at Call ceremonies.

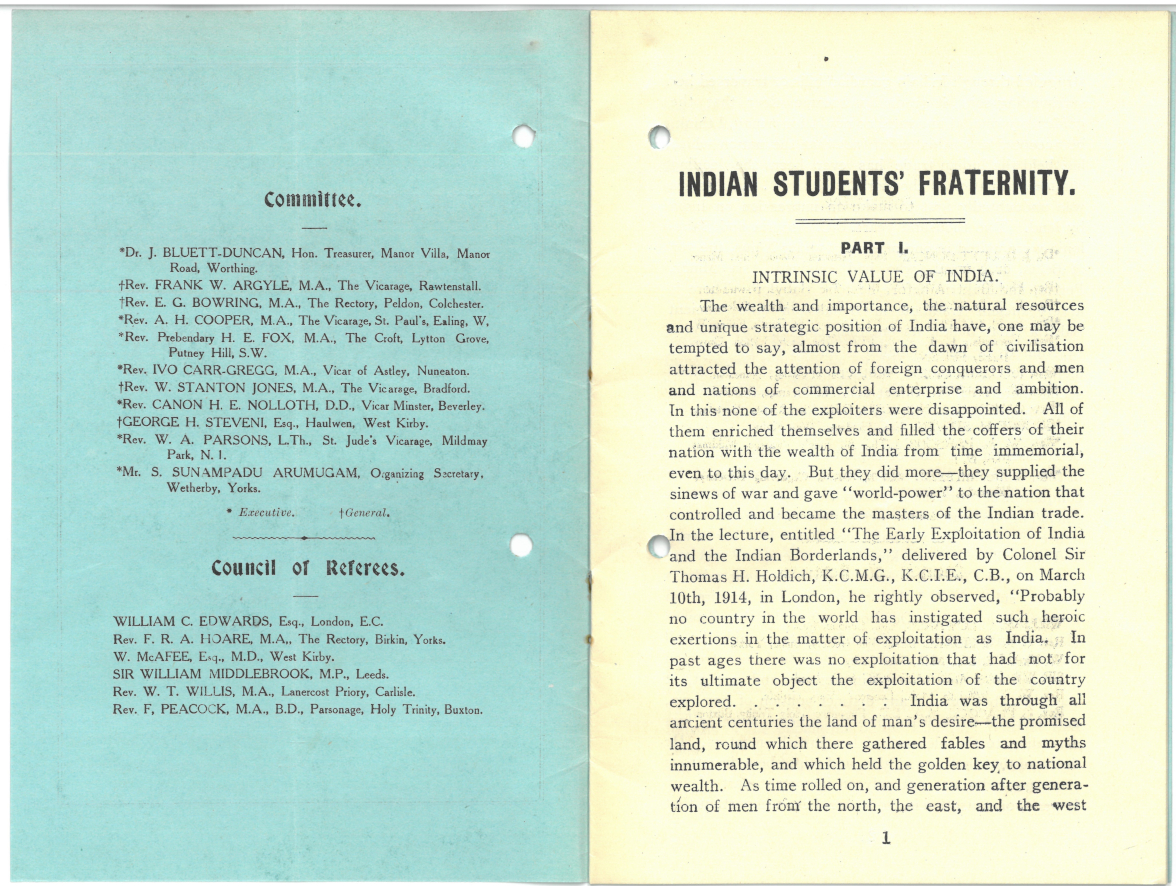

Despite occasional academic, cultural and religious discord, we know that Indian students of the Inn were part of a strong support system that helped each other. Bonnerjee and Tyabli were founding members of the London Indian Society in 1865, one of the earliest societies promoting awareness of the social and political aspirations of Indians in the city. Another student, Sunampadu Arumugam, devoted himself to moral and social service work among fellow Indians for nearly two decades. In 1920, when petitioning for being Called without passing the examination, Arumugam enclosed a brochure titled Indian Students’ Fraternity as supporting evidence. Reaffirming Indian culture and its contribution to the British Empire, materials like this presumably offered students some consolation amidst their transitioning to what must have been a very unfamiliar environment.

Extract of the Indian Students’ Fraternity brochure, 1920 (MT/1/PPE)

The experiences of the early Indian students at Middle Temple testify both to the Inn’s educational achievements and to the importance for institutions to meet the changing needs of their members. Today, an ever-growing number of students from diverse cultural backgrounds join the Inn, and a learning environment that is becoming more embracing and flexible than before certainly plays a role in the realisation of their academic ambitions.