In the present day, coffee is omnipresent in homes, offices and on high streets. It is difficult for a modern person to imagine a world in which this was not the case, but, in England before the mid seventeenth century, coffee was a fascinating rarity. After the foundation of the first coffee houses, the consumption of this beverage became a dominant force in the culture of the country, having the unintended consequence of promoting sober, albeit occasionally bawdy, conversation that inspired some of the intellectual powerhouses of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

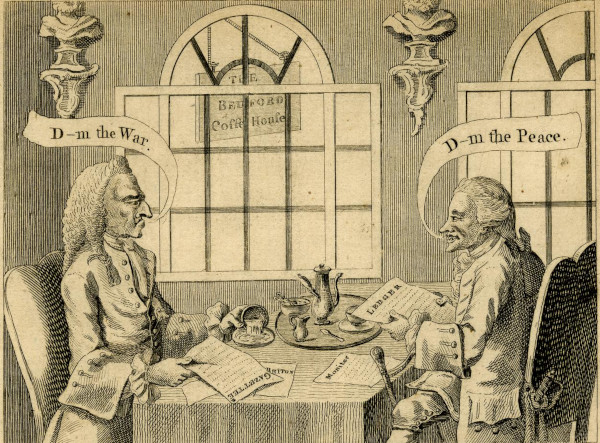

Satirical cartoon of two grumblers at Bedford Coffee House, Covent Garden, commenting on the negotiations for peace near the end of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), 1762 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Prior to the growth in the popularity and availability of tea and coffee, the choice of beverage was much more limited. The Middle Temple’s receipts during this period show that a selection of beers, ales and wines were drunk, but there was also a hot beverage available to wealthier households at this time – posset, a drink of cream, eggs, wine sugar and spices. A 1650 receipt in the Treasurer’s receipt books shows the Inn was purchasing 'sack posset'. Sack was a white fortified wine, often from Spain, which was flavoured with apples, carraway and sugar to make posset, which would be served hot in specialised vessels known as posset pots. The Inn has one of these pots, dating to 1656, in its silver collection, which was donated in 1939 and forms part of the Rothermere Collection.

A silver Posset Pot in the Rothermere Collection, 1656

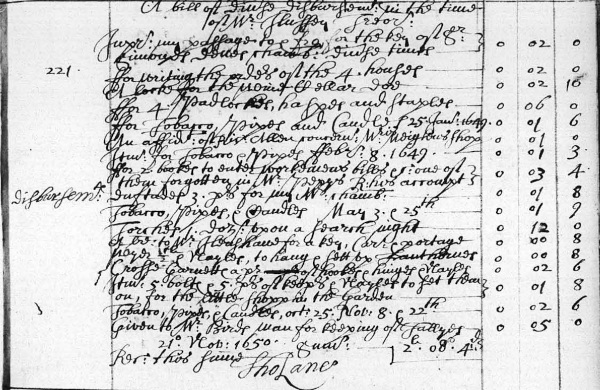

Coffee was characterised as a foreign curiosity in the first half of the seventeenth century. In 1634, Sir Henry Blount wrote from Turkey that the people there had a ‘drink called cauphe… in taste a little bitterish’ and that they entertained themselves daily ‘two or three hours in cauphe-houses, which, in Turkey, abound more than inns and alehouses with us’. John Evelyn, the diarist and Middle Templar, also mentioned the drink – he wrote in 1637, during his years at Trinity College, Oxford ‘there came in my time to the College: one Nathaniel Conopios out of Greece, from [Cyrill] the Patriarch of Constantinople, who returning many years after, was made (as I understood) Bishop of Smyrna… [he] was the first that I ever saw drink Caffè, not heard of then in England, nor til many years after made a common entertainment all over the nation, as since the Chinese Thea; Sack and Tobacco being til these came in the universal liquor and drugs’.

Receipt for expenses including tobacco, pipes and candles, 1649-1650 (MT/2/TRB/8)

Coffee was first popularised in England at public coffee houses, the first of which was ‘The Angel’, opened in 1651 by a Jewish entrepreneur named Jacob in Oxford. The creation of the first London coffee house has been credited to a Pasqua Rosee, the Greek servant to a Mr Edwards, a merchant who dealt in Turkish goods. Edwards acquired the habit for drinking coffee in Turkey and had his servant prepare the beverage for him in London, which soon attracted curious onlookers and tasters. Edwards suggested Rosee set himself up as a vendor and opened a coffee house ‘at the Signe of his own Head’ in St Michael’s Alley around 1652. By the end of the seventeenth century the coffee industry had grown exponentially, and it is estimated that London was home to over three thousand coffee houses.

Interior of a London coffee house, c.1695 © The Trustees of the British Museum

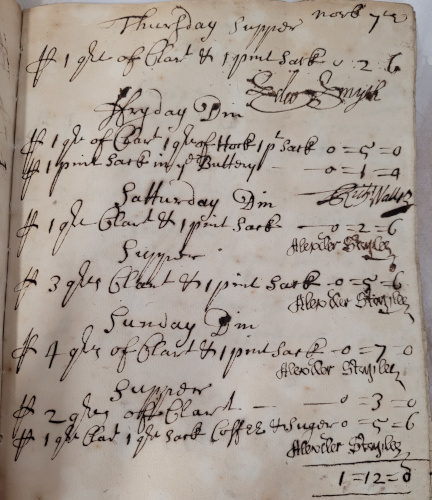

Despite the growing popularity of the beverage, there is no record of coffee being drunk at the Inn prior to being served at a supper on Sunday 10 November 1695, when it was consumed alongside claret, sack and sugar. This may have been because, despite its popularity, coffee was still seen, at least at the Inn, as a new outlandish and extravagant drink. In addition to turning consumers away from native beverages such as beer, coffee houses served as places to read and debate state affairs. This was frowned upon by King Charles II, who issued a proclamation for the suppression of the coffee houses in 1675, although this was cancelled almost immediately due to its widespread unpopularity. This proclamation was also essentially unenforceable, so ubiquitous in English culture had coffee houses become by this time, records relating to which survive in the Middle Temple Archive.

First recorded serving of coffee in the Wine butler’s account book, 10 November 1695 (MT/7/WBA/85)

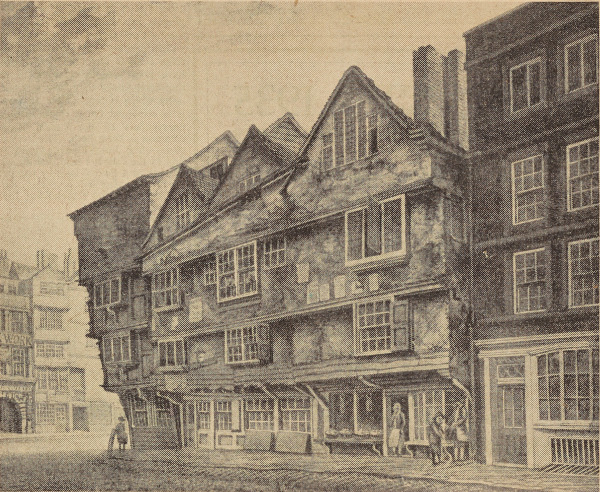

The Rainbow Coffee House of Fleet Street was opened in 1657 by James Farr. It is thought to have been the second coffee house to open in London and was particularly noted as a meeting place for Freemasons and French Huguenot refugees. It was situated at 15 Fleet Street and overlooked both Inner Temple Lane and Hare Court. A deed dated 22 May 1737 describes the property being split into multiple uses – one room for the Rainbow Coffee House, one room for the Nando’s Coffee House, one room for a shop, and various other rooms. The Rainbow Coffee House later became the Rainbow Tavern and was famed for its stout and stewed cheeses. It was rebuilt at great expense in the 1860s and by the 1890s this establishment admitted women, though in a separate upstairs dining room to the men as any woman ‘who dared pass that door labelled ‘coffee room’ would be requested to leave, or at least pointed at as unwomanly’. The Rainbow Tavern closed at some point in the first half of the 20th century.

Reproduction of a painting of Chancery Lane by William Capon, 1798. Inner Temple Gate with the Rainbow Tavern to its right can be seen on the left-hand side of the image (MT/19/ILL/E/E12/13)

While Nando’s Coffee House was mentioned in the some of the same deeds as the Rainbow Tavern, it appears from other deeds that the main premises was situated at 14 rather than 15 Fleet Street. The coffee house is known to have been in existence as early as 1696. However, it did not survive beyond the early nineteenth century, as can be deduced from a deed for 14 Fleet Street, dated 28 November 1828, that describes the premises 'formerly known as Nando’s’. Nando’s was known for its role in the ‘Battle of Temple Bar’ on 22 March 1769, where city merchants processed from the Royal Exchange with an address to King George III in support of his government. The procession was attacked by a mob and the gates to Temple Bar were closed against them for several days. The mob threw dirt and stones at the merchants, and they were forced to leave their carriages and take shelter in Nando’s Coffee House, in a remarkably filthy state.

Satirical print entitled ‘The Battle of Temple Bar’, depicting events of 22 March 1769, with Nando’s Coffee House shown on the left (MT/19/ILL/F/F7/1)

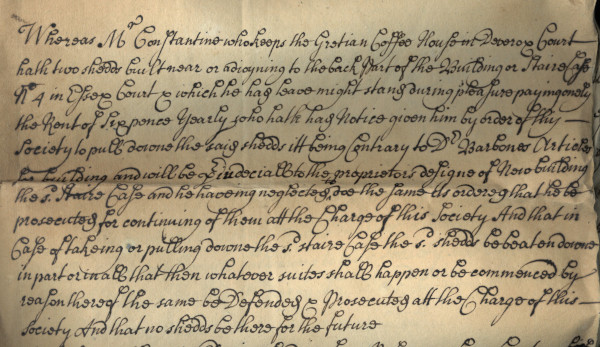

The Grecian Coffee House was established by a Greek called George Constantine in 1665 at Wapping Old Stairs in London, but the premises were moved to the more central location of Devereux Court in 1677, now the Devereux pub. This establishment is famous for being frequented by some of the most famous scientists of the eighteenth century, including Sir Isaac Newton and the astronomer Dr. Edmond Halley, and for being the favourite haunt of Richard Steele, editor of The Tatler. Constantine applied to the Benchers of the Inn in 1684 for leave to finish a building, which may have been two sheds he built adjoining the back of the staircase at 4 Essex Court. In 1715 it was ordered by the Inn’s Parliament that Constantine ‘hath had notice given to him by order of this Society to pull down the said sheds, it being contrary to Dr Barbon’s articles for building, and will be prejudicial to the proprietors design of new building the staircase’. Constantine failed to comply with this order and it was ordered that he be prosecuted for non-compliance. Despite these legal wrangles, the Grecian enjoyed a long occupancy in Devereux Court and appears to have traded until it finally ceased operating in the 1840s.

Document relating to the pulling down of sheds belonging to Mr Constantine of the Grecian Coffee House, c.1715 (MT/21/1/122/10/11)

Temple Coffee House, also situated in Devereux Court, is particularly noted for hosting meetings of what was arguably ‘the earliest natural history society in Britain’, which had a particular focus on botany, and while informal in nature hosted some of the most active natural historians of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Both Temple Coffee House and the Grecian were also frequented by Oliver Goldsmith (1728-1774), a well-known Anglo-Irish novelist whose grave is a prominent feature in Temple Churchyard. Despite hosting genteel customers, it appears that the patrons of this coffee house could sometimes be unruly as the Society felt compelled to erect iron rails outside of the shop in 1789 to prevent customers from climbing out of the windows into New Court. The proprietor of the coffee house, Mrs Woodhouse, submitted a petition objecting to these railings on the grounds that it would ‘look like a dark prison and of course will become very unpleasant to her friends, and perhaps be deserted by many of them’. The Temple Coffee House continued operating until the early 19th century, its premises being referred to in a meeting of the Inn's Parliament in June 1816 as 'formerly the Temple Coffee House', though a Temple Coffee House still appeared to be operating on Pickett Street near the Strand.

![]()

Petition of Mrs Woodhouse, wife of Francis Woodhouse of the Temple Coffee House, to discourage the Society from erecting iron rails outside her shop, c.1790 (MT/21/1/2/5/17)

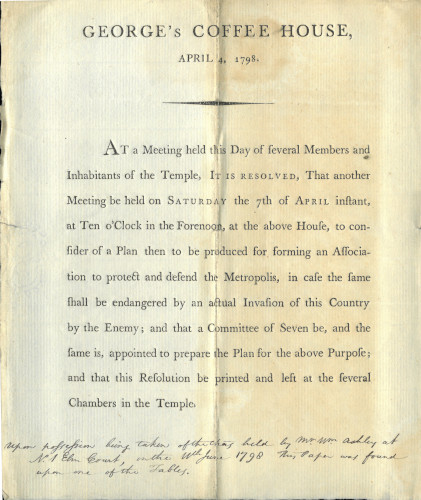

George’s Coffee House was situated at 213 Strand, close to the Grecian, and was also frequented by the Temple barristers. It was used on occasion for meetings, as evidenced by a notice dated 4 April 1798, that called for a meeting at the coffee house of members and inhabitants of the Temple to discus a plan to form an association to defend the city during an invasion by the enemy. This was a period of anxiety between the First and Second Coalitions of the French Revolutionary Wars where suspicions between European countries remained high- the formation of a militia was, therefore, a logical step for the Temple barristers to take considering they had taken the same precautions during previous conflicts. The threat of invasion by French forces, and presumably the anxiety of the barristers, would not abate until the Battle of Trafalgar was won in 1805, gaining Britain naval supremacy and preventing the transportation of enemy troops across the British Channel.

Printed notice of a meeting of members and inhabitants of the Temple to be held at George's Coffee House on 7th April to consider a plan for forming an association to defend the Metropolis in the event of invasion by the enemy. 4 April 1798 (MT/17/3)

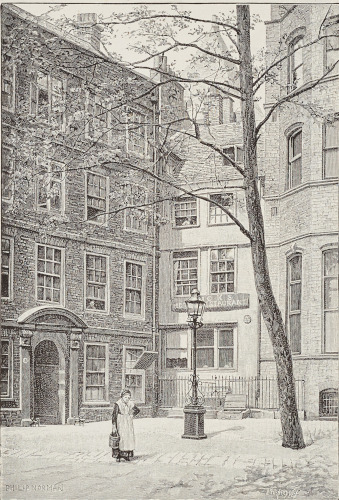

Richard’s Coffee House, also known as Dick’s Coffee House, is the establishment that is best represented in the Archive. Situated at 8 Fleet Street, it was opened in 1681 by Richard Torner or Turner for whom the establishment was named. It was said in 19th century publications to have been a favourite of the residents of the Temple, who took exception to a Drury Lane farce because they believed that the characters represented the beloved proprietor of Dick’s, Mrs Yarrow, and her daughter. The young barristers apparently banded together to see the play on its opening night and ‘hissed the piece off the boards’. The 1737 publication of the play created further outrage by using of an image of Dick’s as the chosen illustration for its frontispiece, thereby further emphasising the association. The coffee house continued to operate through much of the 19th century but was converted into a hotel and restaurant around 1875. The venue closed its doors for the final time in the summer of 1897 and the building was demolished and rebuilt in 1899 so that the Legal and General Insurance Company could extend its premises.

The back of Dick’s Coffee House from Hare Court, 1889 (MT/19/ILL/E/E5/1)

Coffee culture and the coffee houses surrounding the Middle Temple experienced their heyday during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and would have been an important social focal point for students, barristers, and judges of the Inn during this period. These businesses provided a setting where they could, unaffected by the consumption of alcohol and its consequences, form the vitally important social networks of the time, and to discuss points of law, politics and recreation.

Silver coffee pot in the Inn's silver collection, 1750