The site of the Middle Temple and the wider Temple precinct has seen continuous occupation for over 800 years, with the Templar Order being the first recorded occupiers of the area, at least as early as the consecration of Temple Church in 1185. Hundreds of people have lived and worked at the Temple over the centuries, and it is an unfortunate fact that where people live and work they will also eventually die and need to be laid to rest. There is little visual evidence of this fact at the Temple of the present day, with scant funerary inscriptions to be seen in Temple Church in comparison to several centuries ago and few tombs visible in the Churchyard. However, hundreds of people have been buried in the area, some in unexpected places.

Print of Goldsmith’s Tomb in 1860, engraved in 1874 (MT/19/ILL/C/C7/18)

While the first recorded occupiers of the Temple were the Knights Templar, there is archaeological evidence of human activity on the site at a much earlier date than the 12th century. From 1999-2000 an excavation was carried out in areas including Hare Court prior to construction work. A skeleton was discovered with a sword, and the grave was thought of pagan Saxon date (pre-7th century) due to the inclusion of the weapon, as Christian burials do not tend to include grave goods. This burial, together with other possible graves of a similar date, suggests that the Temple was the site of an early Saxon cemetery beyond the eastern boundary of Lundenwic, the Saxon town built near to the ruins of the Roman town of Londinium, centred on what is now Aldwych.

A 7th century Saxon sword discovered in Twickenham, similar to the sword found in the Hare Court grave but in better condition © The Trustees of the British Museum

Little is known about the earliest burials at Temple Church, and even the identities of the knights that were buried beneath the famous Templar effigies remain the subject of much speculation. Three of the effigies represent William Marshall, Earl of Pembroke, and his sons Gilbert and William the Younger, but the identities of the others remain unknown. One was once thought to be an effigy of Geoffrey de Mandeville, 1st Earl of Essex, but this was later disproven. Mandeville rebelled against King Stephen in favour of Empress Matilda and was excommunicated. He died attacking Burwell Castle in 1144, and because of his disreputable life his unshriven body was denied a Christian burial at Waldon Priory, a monastery he founded. The Templars carried him to the Old Temple in the parish of St Andrew, Holborn, and placed his body in a lead coffin which was either left hanging in a tree or thrown in a pit outside consecrated ground. Twenty years later, Mandeville was granted absolution by the Pope, and his remains were interred in the newly consecrated ground at the New Temple, now known as Temple Church, around the year 1163.

Woodcuts of the effigies of the Knights Templar from Charles Knight’s Magazine, 1832 (MT/19/ILL/C/C7/15)

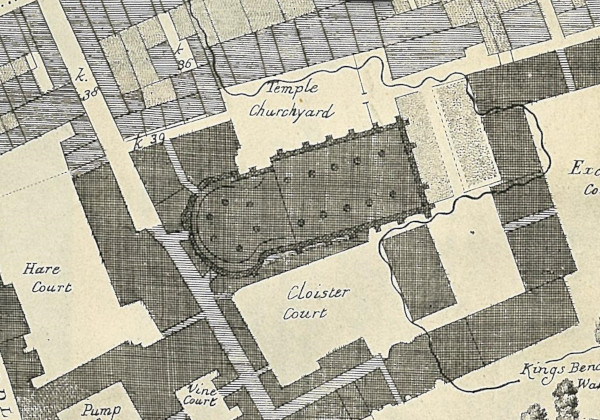

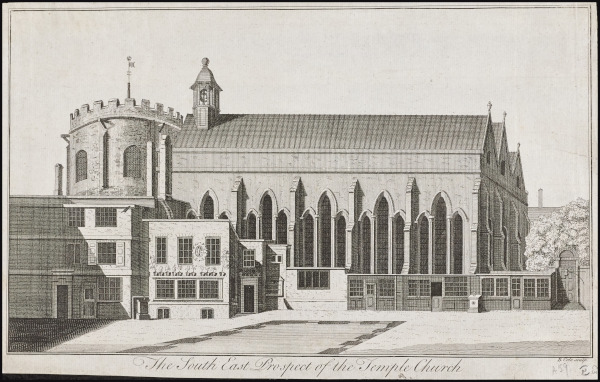

With no written records produced by Temple Church having survived from between the year of its consecration in 1185 to the 17th century, research into burials during this period relies heavily on archaeology. The 1999-2000 excavations also investigated Churchyard Court and discovered that, in addition to the small North Churchyard, there used to be a South Churchyard. The name of the North Churchyard has always suggested that it might have its counterpart to the south of the Church, but it was not until these excavations that this was fully established. One trench dug in Churchyard Court revealed six graves containing five skeletons between them and it was discovered that there had been two phases of burials in the South Churchyard; earlier 16th-17th century graves and later 17th century graves. Archaeologists suggested that this area was probably only used for burials until the construction of the Lamb Building in 1667 or its predecessors dating from 1596 onwards.

Plan of the Temple showing the North Churchyard with ‘Cloister Court’ and the Lamb Building to the south, 1677

The human remains that were discovered only represent a small sample of the total number of occupants in the cemetery, so generalisations about the whole population are difficult to make. However, it is interesting that the individuals in the graves were all young - four of the skeletons were young adults and one was a juvenile. If this were representative of the whole, the Churchyard would show a youthful population in comparison with other contemporary cemeteries. Additionally, the skeletons all showed high incidences of poor dental hygiene, suggesting they may have been high-status as sugar was very expensive during the 16th-17th centuries. A cemetery containing fairly wealthy young men would fit with the Inns’ role as the ‘Third University’ of England around this period.

The south side of Temple Church, 1756 (MT/19/ILL/C/C3/2)

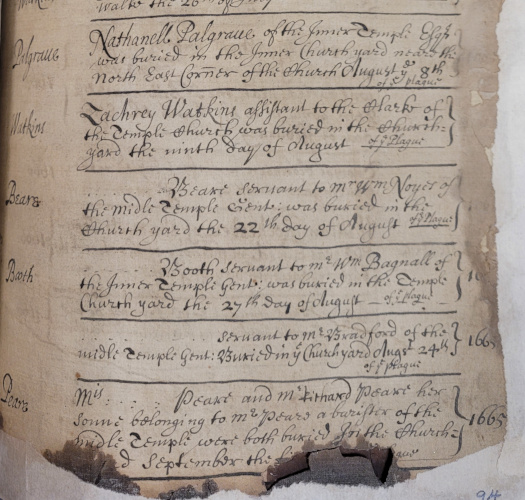

The Churchyard may have extended further west towards Middle Temple Lane at one time, but there is currently scant evidence for this. Human remains have been found in this area - in 1878 builders were underpinning the last house on the west side of Middle Temple Lane, occupied by the Under Porter, and came across large quantities of human bones in five regular rows in a single grave. Unfortunately, archaeological science was in its infancy at this time and an entire cartload of leg bones were unceremoniously removed with the remainder of the skeletons being left under the house. No dating material was recovered meaning that these graves may have dated from any time from the Roman period to the early modern period. Later archaeologists have suggested it was either a grave for the poorer members of the Temple’s community, a mass burial during the Black Death, or an Anglo-Saxon cemetery. It was unlikely to be a mass grave created during the plague of 1665 as only twelve individuals were recorded as having died of plague in the Church’s records.

Burial records of plague victims in the Temple Church Burial Register, 1665 (MT/15/REG/1)

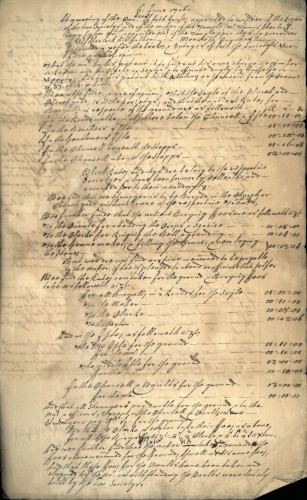

The first written record of burials in Temple Church was finally created in 1628. It was known as the ‘Catalogue of Burialls’ and was begun by the controversial Master Micklethwaite, who may possibly have started the Register partly as a method of keeping track of fees he was owed for burials. These varied depending on the location of the burial, with the importance of the individual, and the amount of money their estate was willing to pay, determining the position of their final resting place. The most desirable area was the chancel above the stairs, a plot that cost £2 in 1706, and the cheapest in the Church were the walks of the Round, which cost a quarter of that sum at 10 shillings. It is striking how few people were buried in the Churchyard relative to the Church in the 17th century – members of the two Inns show a marked preference for being interred inside the building, along with their wives, children and senior officers of the societies. In a period of 35 years ending in 1662, there were 60 interments in the Round and 250 within the Oblong Church. The Churchyard for much of this century appears to be used only for the more junior servants of the Inns, tradesmen and ‘strangers’ who died in the Temple grounds, though no strangers were to be buried at Temple Church without express permission of the Benchers.

Report of a joint Committee appointed to consider the rights of the two Inns and the Master of the Temple, Thomas Sherlock, regarding burials, 6 June 1706 (MT/15/TAM/124)

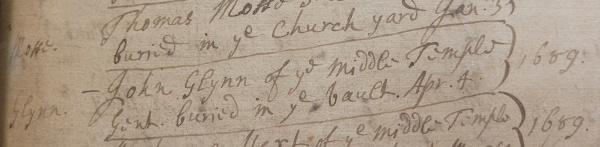

By the 1680s it was increasingly difficult to find burial space in the oblong part of the Church. A solution was found in the construction of vaults for the two Inns, with the earliest evidence for the vaults being found in the Inner Temple records when the Society paid a bricklayer for the construction of their vault in 1684. The earliest burials in these new vaults were recorded in the register in 1689. The first mention of the vault in the Middle Temple records is in the minutes of the Inn’s Parliament of 7 February 1690, which state ‘Master Treasurer shall set the rates for burials in the Middle Temple vault till further notice’. The Benchers of the Inner Temple subsequently attempted to bar the Master of the Temple from burying anyone else in the chancel or body of the Church, but burials within it continued periodically after this.

The first recorded burial in Middle Temple’s vault in Temple Church - John Glynn who was buried on 4 April 1689 (MT/15/REG/1)

After the construction of the vaults, more members of the Inns opted for burial within the Churchyard than had done so previously. From this point the demographics in the registers also begin to shift as more families took residence in chambers, with more women and children being represented in its pages. Tragically, there was an explosion in infant deaths, a result of hundreds of foundlings being abandoned in the lanes and staircases of the Temple from the 17th century to the 1850s – these children frequently came from impoverished backgrounds and were already often in poor health when they came into the care of the Temple during an era of high infant mortality. Many of these children did not survive and were subsequently buried at Temple Church.

Tombs uncovered in the North Churchyard after excavation work in 1861 (MT/19/ILL/C/C3/45)

By the beginning of the 19th century the number of burials in the Churchyard was starting to cause a logistical problem, just as burial within the Church had around 150 years earlier. By this time there were very severe difficulties finding space for burials in both the vaults and Churchyard. On 19 June 1801 it was ordered that ‘the vault belonging to [the Middle Temple] in the Temple Church be used for the only purpose of depositing the remains of such gentlemen as have been Masters of the Bench and that burials without the Church be confined to such persons as have been Members or Officers of this Society’. The two Inns also restarted efforts to prevent all burials within the Church. On 6 February 1818, the Middle Temple’s Parliament made an order that ‘no corpse be interred in that part of the body of the Church or of the Round belonging to the Middle Temple except in the Benchers’ vault’. Additionally, no new monuments were allowed within the Church ‘except to the memory of eminent and distinguished persons and such as may be ornamental to the Church and to be directed by a special Order of Parliament for that purpose’, with Inner Temple making a similar order a few years earlier on 14 May 1813.

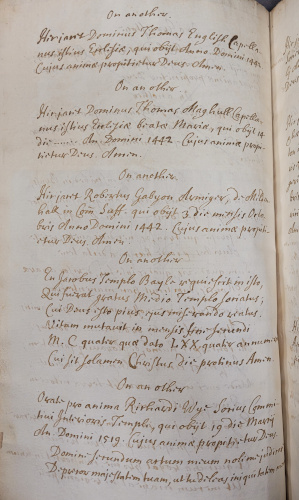

Manuscript book entitled ‘Epitaphs and Inscriptions in the Temple Church’, early 18th century (MT/15/MIV/1)

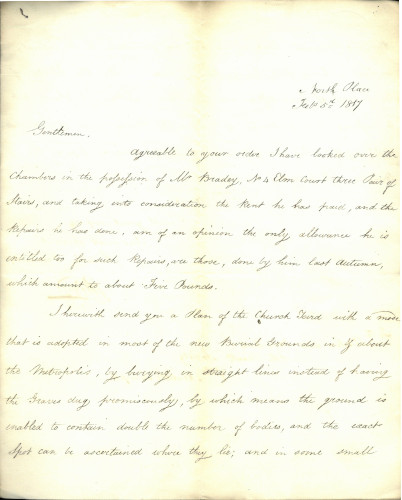

The Benchers also considered new methods of organising the Churchyard as shown by a letter written to them in 1817 by J. Wigg, the Society’s surveyor. Here he reports on the plan adopted by many of the new burial grounds in London, where graves were dug in straight lines, allowing the graveyards to hold double the normal number of bodies. He also suggests limiting lead coffins to a particular spot and that graves be dug to a considerable depth. It is unclear whether Wigg’s suggestions were adopted.

Letter from J. Wigg, surveyor, to the Benchers of the Middle Temple describing layouts of new cemeteries, 1817 (MT/15/TAM/241)

By 1840 the cemetery was considered to be exhausted. In a report of the Committee for repairing and improving Temple Church on the 20 November, it is stated that ‘the present confined and crowded state of the church yard presents a proper occasion when the Societies should give effect to the prevailing opinion that the continuance of cemeteries in the midst of a dense population is most injurious to health by prohibiting any future interments in the church yard except in the case of Mr Withers to whom the Society of the Inner Temple have already given a promise’. Burial at Temple Church ceased all together after an Act of Parliament was passed in 1853, ‘An Act to ament the Laws concerning the Burial of the Dead in the Metropolis’. For the purposes of the Act, the two Societies were considered to be part of the Metropolis and burials were from that point on forbidden by law at the Temple.

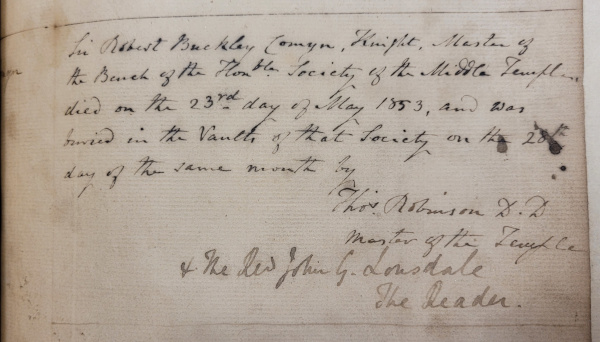

Burial record of Sir Robert Buckley Comyn of the Middle Temple, the last person to be buried in Temple Church, 28 May 1853 (MT/15/REG/3)

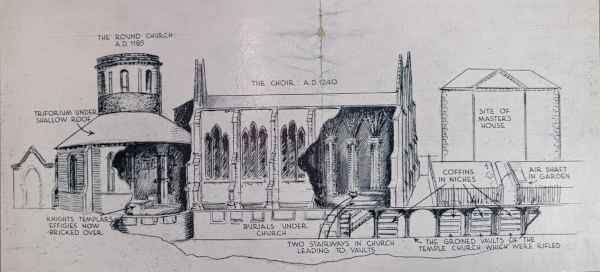

Unfortunately, the dead of Temple Church were not left to their peaceful rest. After the devastation to the Church caused by bombing during World War Two, looters riffled through the ruins. In search of treasures such as jewellery, they broke into the Church’s burial vaults, smashing coffins and disturbing bones. The also reportedly stole the skull of Geoffrey de Mandeville, 1st Earl of Essex, which created some suspicion that a private collector may have been involved. After the raid the entrances to the vaults were bricked up and sealed to restore quiet and dignity to the dead, but this previously obscure burial place for members of the Temple community was irrevocably exposed by the incident, provoking the interest of scholars of London’s history in the occupants of its subterranean passages.

Diagrammatic sketch of Temple Church and its burial vaults from The Sphere, 27 September 1947 (MT/19/SCR/2)