From the establishment of the Church of England in the mid-16 th century until well into the 19 th , Roman Catholics in England faced varying levels of persecution, discrimination and obstacles in both private and public life. State and popular mistrust of Catholics made itself felt in a number of ways at the Middle Temple, affected some of its most prominent members and has left a substantial documentary trail in the Inn’s Archive.

Although Henry VIII broke from Rome and established the Church of England in the 1530s, over which he rather than the Pope held full authority, he remained himself committed to Catholic doctrine and was no Protestant. The doctrinal pendulum swung back and forth after Henry’s death, first with the short reign of his son Edward VI, a committed Protestant, and then with the reestablishment of Roman Catholicism under Mary I and her husband Philip, King of Spain, whose reign, in which hundreds of Protestants were executed, ended with Mary’s death in 1558.

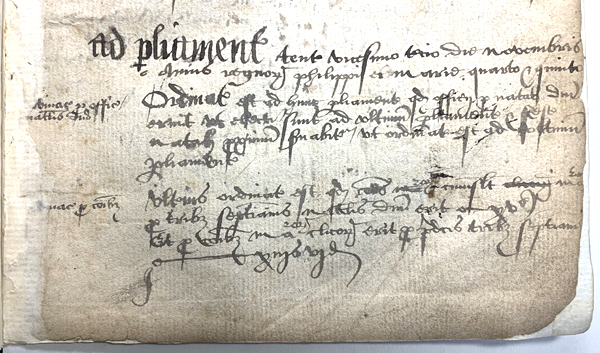

Minutes of Parliament dated to the fourth and fifth year of the reign of ‘Philippi et Marie’, 23 November 1557 (MT.1/MPA/3)

Mary’s half-sister Queen Elizabeth I, raised a Protestant, passed laws early in her reign requiring her subjects to worship in the Church of England, and over the course of her time on the throne the persecution of Catholics increased. The Elizabethan state was intensely preoccupied by anxiety that Catholics living in England were sleeper agents of the Pope in Rome, intent on bringing down the prevailing Anglican regime. These concerns were only compounded by the secular threat represented by the Catholic monarchs of France and Spain.

The agents of the Queen cast their suspicious gaze upon the Inns of Court, fearful that they were providing sanctuary and even support for Catholic subversion. Surveys were undertaken for the Privy Council, reporting on membership, accommodation and religious affiliation within the Inns. Allegations were made that the Middle Temple was ‘pestr’d with papists’, and the Catholic Under Treasurer, Thomas Pagitt, was eyed with particular suspicion.

Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I, Middle Temple Hall

Regulations within the Inn were enacted to enforce Anglican adherence, presenting serious spiritual difficulties for Catholic members wishing to be admitted and Called to the Bar. On 25 November 1580, the Middle Temple Parliament ordered that every member of the Inn should receive Holy Communion three times each year, and from 1583 members had to pledge on admission to conform with the established faith, take communion and obey royal authority.

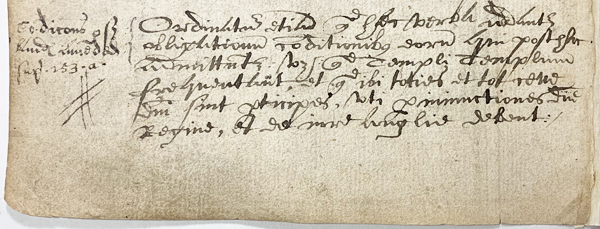

Order of Parliament adding terms to the pledge made on admission to the Inn, 27 November 1583 (MT.1/MPA/3)

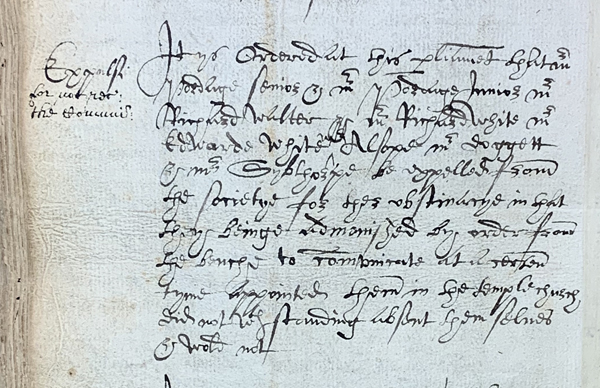

The Inn began to order the expulsion of members suspected or accused of Catholic sympathies or practices. For example, in June 1588 eight men including a Mr Sibthorpe and a Mr Walter were expelled ‘for their obstinacy in that they beinge admonished to communicate in the Temple Church did notwithstanding absent themselves and wold not’. Sibthorpe was later re-admitted, but only after having demonstrated his ‘detestation of the popish religion’ in writing, and Walter was ordered to ‘have conference touching his religion’ with Richard Hooker, the Master of the Temple and a prominent theologian of the day.

Order of Parliament expelling eight members of the Inn for absence from Holy Communion, 21 June 1588 (MT.1/MPA/3)

One prominent figure in Middle Temple history who faced and navigated these challenges was Edmund Plowden. Born around 1520 and admitted to the Inn at around the age of 20, he served as Reader in 1557 and 1561, then as Treasurer from 1561 to 1570. He maintained his adherence to the Roman Catholic faith throughout the turbulence and reversals of the mid-century, and was elected as an MP under Mary I, being thought of by the Queen as among the ‘wise, grave and Catholic sort’ she preferred. A successful lawyer, he was due to be appointed Serjeant-at-Law, but when Mary died his name was removed from the list of candidates by the new regime.

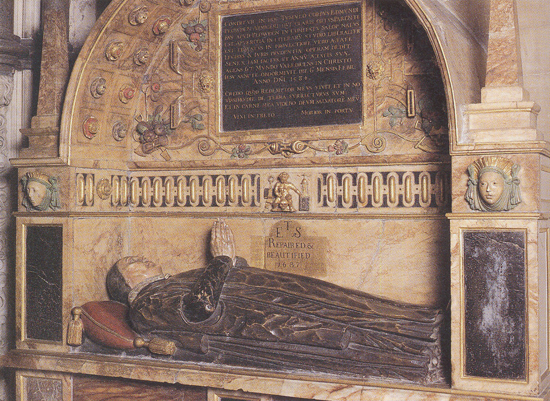

Marble bust of Edmund Plowden, Middle Temple Hall

Plowden stuck to his faith, and his progress towards high office halted, while he became known for defending his co-religionists in court. As Treasurer of the Middle Temple, he masterminded and oversaw the construction of Middle Temple Hall, for which he is remembered by a marble bust beside the screen. Despite his well-known adherence to the old order – being accused in 1580 of allowing the Inn to become a den of papists - he was a favourite of Elizabeth I and is said to have been invited by her to become Lord Chancellor. He excused himself, saying:

‘ Hold me dread sovereign excused… I should not have in charge Your Majesty’s conscience one week before I should incur your displeasure’.

Dying in 1585, he was buried in Temple Church, and his monument and effigy stand there to this day.

Monument & Effigy of Edmund Plowden, Temple Church

A symbolic curiosity in Hall, which attracts comment to this day, can be found high up in the west window where, alongside Paschal Lambs and Tudor Roses, is a stained glass representation of a pomegranate. This fruit had been adopted as the personal badge of Catherine of Aragon – Henry VIII’s first wife and mother of the aforementioned Queen Mary I, who had also used it as her symbol and a mark of her heritage. Given the intense official anxiety about the Catholic threat (not least from Catherine and Mary’s relatives in Spain), the crucial importance of symbolism and iconography in the Elizabethan era, and the suspicion being directed at the Middle Temple, this is perhaps a surprising inclusion - even given the Hall’s construction under the auspices of Edmund Plowden.

Stained glass depicting a pomegranate, Middle Temple Hall

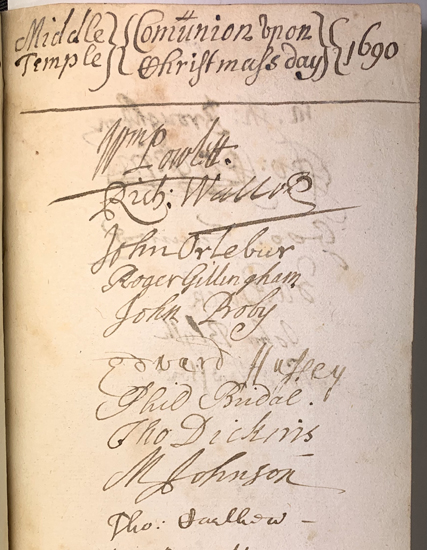

The persecution of Catholics continued under Elizabeth’s successor, James I, despite early hopes of great lenience. Fear and hostility only grew after the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, an attempt by a group of Roman Catholics to blow up the House of Lords with the King inside. Further regulations were passed by the Benchers in the Inn to mandate the taking of Holy Communion in Temple Church, which seem to have been enforced more energetically at times of heightened political tension. A series of volumes survive in the Inn’s Archive that communicants from butlers to Benchers were required to sign, as evidence of their presence and adherence to the Anglican Church.

Middle Temple Book of Communicants, Christmas Day 1690 (MT.15/COM/3)

Under three successive kings – Charles II, James II and William III, whose portraits hang together in Middle Temple Hall - the changing and challenging fortunes of English Catholics continued through many further twists and turns. Following the end of Oliver Cromwell’s punishing and puritanical regime, the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 brought hope for more favourable treatment. Charles II attempted to increase religious liberty with the Royal Declaration of Indulgence in 1672, though it was eventually withdrawn following intense opposition from Parliament and Church alike.

Charles was succeeded by his brother, James II, himself a Roman Catholic, who also attempted to extend religious toleration in 1687. In doing so, he helped to precipitate the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which saw Parliament invite his Protestant son-in-law, William of Orange, to invade and take the throne with James’ daughter Mary. Under William and Mary, Catholics were officially excluded from practicing at the Bar – a regulation which would remain in place for nearly a century.

Portraits of Kings Charles II, James II and William III, Middle Temple Hall

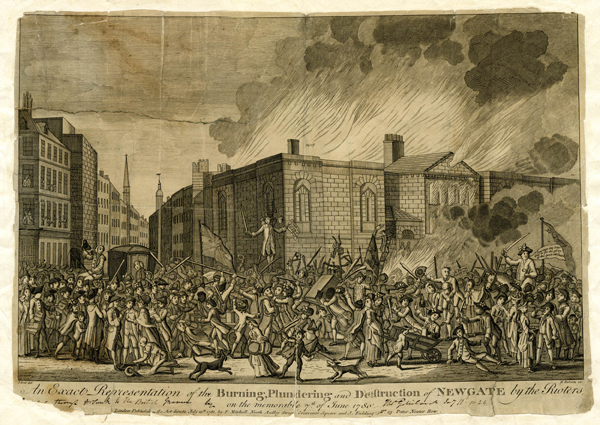

As the eighteenth century went by, the penalties imposed in the previous centuries began to fade in enforcement, though life was far from straightforward. In 1778, Parliament passed the ‘Papists Act’, mitigating some of the official discrimination against Catholics (and allowing them to join the armed forces, in which they were desperately needed as the American War of Independence went from bad to worse for the British). Public disquiet following the passage of this act was whipped up by Lord George Gordon of the Protestant Association into an anti-Catholic frenzy, leading to several days of violence and mayhem in the summer of 1780, known to history as the Gordon Riots.

Engraving depicting the destruction of Newgate Prison during the Gordon Riots, June 1780 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Spreading across London, the riots reached the precincts of the Temple, and history relates that one Joseph Stacpoole, an Irish Catholic barrister with chambers in Essex Court, may well have saved the Inn from destruction. A well-established figure in the Inn’s Irish Catholic community, which frequently gathered in the Grecian Coffee House (now the Devereux pub), he got wind of a planned assault on the Temple, and managed to assemble a company of 20 Irish law students to defend the Inn. While they were later joined by many other volunteer barristers and students, their timely actions may have been key to saving the Temple from the devastation and looting wrought elsewhere.

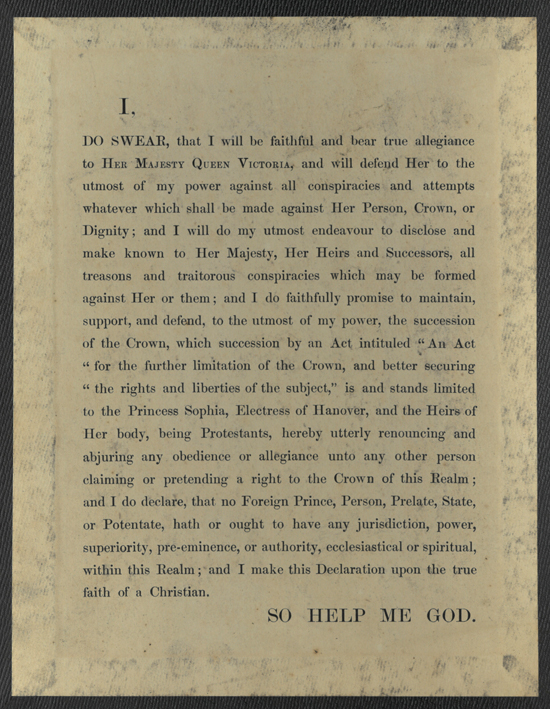

Eleven years later, the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1791 was passed, which went much further than the act of 1778 – it was this Act that once and for all opened the legal profession to Catholics. However, it also required them, in order to take advantage of these newly-conferred rights, to give an oath of allegiance on Call to the Bar. There are several examples of such oaths in the Archive. Oaths taken the reign of King George IV required barristers to declare ‘I do not believe that the Pope of Rome, or any other Foreign Prince, Prelate, State or Potentate hath or ought to have any Imperial or Civil Jurisdiction, Power, Superiority, or Pre-eminence within this Realm’. Similar oaths were required of Quakers and other non-Anglicans, and the practice continued well into the reign of Queen Victoria.

Oath of Allegiance given by Roman Catholics on Call to the Bar during the reign of Queen Victoria (MT.1/OTH)

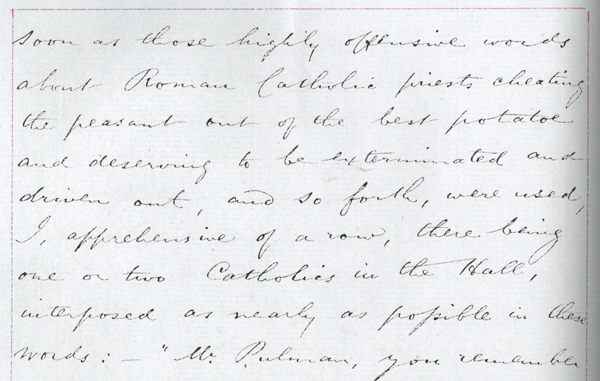

While the official position had improved and many barriers been lifted, Catholics still encountered difficulties when navigating society, and points of contention certainly arose at the Middle Temple. A disciplinary case was brought in 1869 by one Middle Templar, Thomas Chisholm Anstey, against another, John Pulman, that illuminates how conflict could easily flare up. Anstey, a prominent Catholic barrister, one of the first Catholic Members of Parliament and former Attorney General of Hong Kong, complained that during the course of dinner in Hall, Pulman had, while intoxicated, used insulting language while engaged in an argument concerning the disestablishment of the Irish Church. Pulman, said Anstey, had spoken about ‘Roman Catholic priests cheating the peasant out of the best potato and deserving to be exterminated and driven out’.

Extract from the proceedings in the disciplinary matter of John Pulman, 25 June 1869 (MT.3/DIS/11)

The history of Roman Catholics in the Middle Temple, then, is intertwined with the external political, social and theological context in the world outside. Exceptions such as Edmund Plowden do not detract from the fact that Catholics suffered greatly as a result of the Inn’s official policies and the regulations governing Call to the Bar over many centuries, not to mention a sometimes hostile social environment persisting after official limitations had been removed. In 1968, the Inn made Cardinal John Heenan, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Westminster, an Honorary Bencher. During the ceremony, he paused, as custom dictates, beside the bust of his co-religionist and fellow Bencher of many centuries earlier, Edmund Plowden.

Some of the items and themes discussed in this article can be found in the Hilary 2020 exhibition in Middle Temple Library, 'Becoming a Barrister'.