As the shortest day of the year draws near, the Middle Temple is illuminated by bright electric lighting and the soft glow of gas streetlamps. In the late 19 th century, the Inn developed what would have been seen as a supernatural ability in centuries past – the ability to turn the night as bright as day. In these days of round-the-clock electrical lighting, it is easy to forget the importance that light played in day-to-day life prior to its invention. The dark nights of winter imposed many limitations, expenses and dangers on the inhabitants of the Inn, which lessened with gradual improvements in technology.

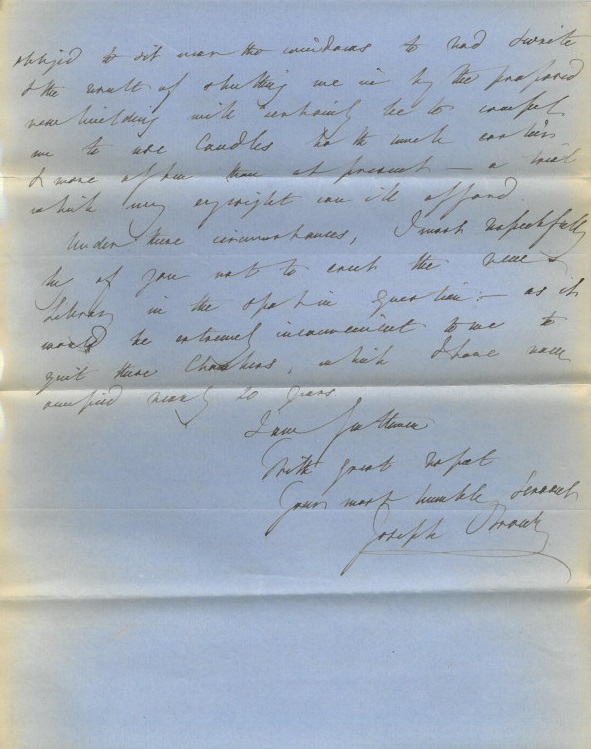

Natural light was the primary means by which people worked and rights to it were fiercely defended. Disputes over light led to battles between the two Temples and with their tenants. One such instance involved the building of the Victorian library, which opened in 1861. Joseph Brown of 2 Essex Court was one of the people impacted by this new building and wrote to the Benchers in 1856 stating that ‘in the dark days of winter and spring, my chambers are even now so short of light that I am obliged to sit near the windows to read and write and the result of shutting me in by the proffered new building will certainly be to compel me to use candles to be much certain and more often than at present, a trial which my eyesight can ill afford’.

Letter regarding the blocking of light from Joseph Brown of 2 Essex Court, 10 February 1856 (MT/21/24/YE)

For many centuries, candles were the only means, besides tiny rushlights, by which a person could see and work after dark. The expense of candles prohibited people from working too late into the night. Many people could not afford high quality beeswax candles and were forced to make do with tallow candles. Middle Temple itself ordered both types. Beeswax candles burnt with a brighter light, lasted longer, and smelt better than those made of tallow. A receipt dated 17 June 1646 records that these candles were provided to the Court of King’s Bench and it is elsewhere recorded that they were provided to Temple Church. It is probable that they would have been used by Benchers and provided for special events. In contrast, tallow candles, usually made of beef or mutton fat, were smoky, dim and smelt unpleasant. They would have been the candles used by the Inn’s servants. In addition, they required constant attendance and trimming to lessen their tendency to sputter and smoke. The use of candles as a practical light source, rather than for ambience, probably persisted until the installation of the first electric lights. A newspaper article written in 1935 reported of past dinners in Hall, ‘formerly the members and students were expected to bring their light with them – candles, which they placed in metal holders on the tables’. The fact that members had to bring their own lights, instead of being provided them, further illustrates the expense of candles.

Silver Candle Snuffer Stand with Snuffer Scissors used for extinguishing candles and wick trimming, 1690

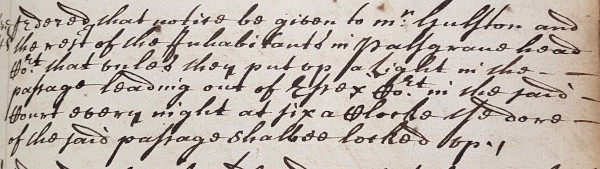

The earliest form of street lighting in the Temple was in the form of lanterns, or ‘lanthorns’. The Middle Temple provided some of these lanterns, the repair of these being a regular annual expense in the Treasurer’s Receipt Books from the 17 th century and carried on to a reduced extent after alternate forms of street lighting became more prevalent. Tenants of chambers were also expected to do their part to help ensure the courts and streets of the Temple were safe and well lit, accidents and crime being hazards of unlit areas, and penalties were imposed on those that did not do their civic duty. An order of Parliament dated 28 January 1697/98 commanded that ‘notice shall be given to Mr Gulston and the other inhabitants in Palsgrave Head Court, that unless they put up a light in the passage leading out of Essex Court every night at six o’clock, the door of the passage shall be locked up’. Despite the best efforts of the Inn, these lanterns, which used tallow candles, would have provided only very limited illumination and would frequently extinguish during the night.

Order of Parliament commanding that tenants put up a light in the passage leading out of Essex Court every night, 28 January 1697/98 (MT/1/MPA/6)

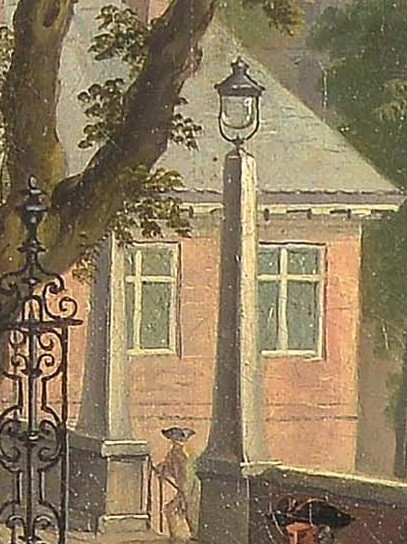

In 1724 a new type of street light came to Middle Temple, a ‘convex’ oil lamp, which gave a cleaner, brighter and more reliable light than the previous lanterns. Fifteen lamps were initially installed and the Conic Lamp Office was responsible for their supply and maintenance. This trial appears to have been a success for the Society, as on 6 June 1729 the Treasurer was ‘empowered to treat with the lamp office… to have this Society… well illuminated with the new made globular lamps, one to be fixed at every door case and at all other places in and about the Society as Mr Treasurer shall in his opinion apprehend to be most convenient and necessary’. From 1729, forty five globular lamps lit the streets and courts of the Middle Temple. By 1740 this had grown to sixty lamps.

Globular Lamp in the painting ‘Fountain in the Temple’ by Joseph Nickolls, 1738

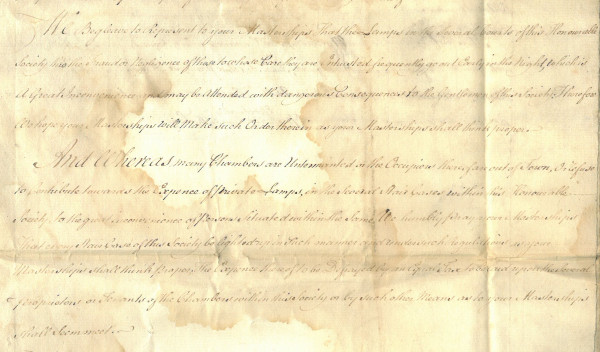

From 1738 a lamplighter was employed directly by the Inn. Lamplighters typically lit the lamps at the beginning of the evening and extinguished them at dawn, though they were not always diligent in their duties. An 18 th century petition from students and barristers complained about the lamps of the Inn, reporting that due to ‘fraud or negligence of those to whose care they are entrusted frequently go out early into the night, which is a great inconvenience and may be attended with dangerous consequences to the Gentlemen of this Society’. The lamplighter in question may have been Sam Birkes, who was employed as a lamplighter by the Middle Temple in 1771 and was dismissed in 1777 ‘for neglect of duty’. The role of lamplighter has persisted into the 21 st century and five lamplighters are currently employed by British Gas to operate and maintain the 1400 gas lamps around London, including those still within the Temple precinct.

Petition from students and barristers including a request for improved lighting, 18 th century (MT/21/CIX/I/2)

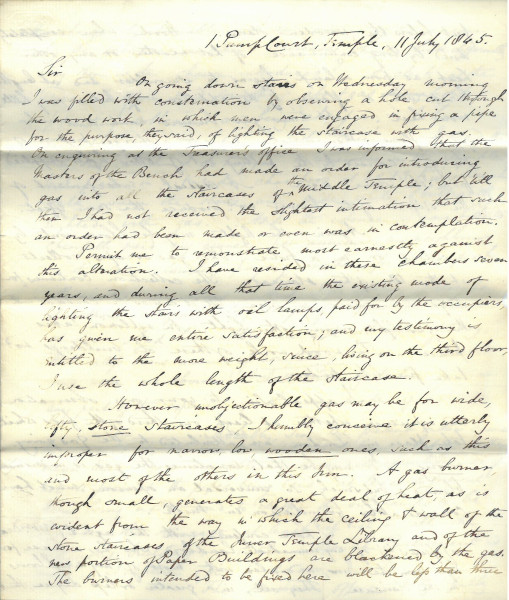

Gas lighting provided a much brighter light than oil lamps and the decision to install it in the lanes and courts of Middle Temple was made in 1817. It was introduced to internal areas at a much later date, being installed in the staircases of chambers in the 1840s and within the offices and internal areas of the Inn in 1857. The installation of internal gas lighting was not without its opponents. A letter from J.C. Heath of 1 Pump Court dated 11 July 1845 objects to its installation, stating ‘the existing mode of lighting the stairs with oil lamps paid for by the occupiers has given me entire satisfaction’. He also expressed concerns about the safety of gas, concluding his letter with the dramatic statement ‘I must content myself with praying that the Society may next term have any of their buildings remaining to light at all’. The previous method of lighting the staircases had its disadvantages, however, as the aforementioned 18 th century petition also complained that untenanted chambers, or those whose occupiers were out of town ‘do refuse to contribute towards the expense of private lamps in the several stair cases within this Honourable Society to the great inconvenience of persons situated within the same’.

Letter of complaint from J.C. Heath of 1 Pump Court regarding the installation of gas lighting, 11 July 1845 (MT/21/XV/VI/2)

Gas was not the only option available to the Inn for new lighting in the 1850s. A gentleman named James Price, in a letter dated 26 April 1850, requested that the Inn consider electric lighting before committing to gas. The electric light had many advantages over gas – its brightness, constant non flickering light, lack of pollutants, ability to view colour at night and improved safety. Price, however, was ahead of his time – electric lighting was in its experimental stages at this point and was not ready for widespread adoption. The denizens of the Middle Temple had to wait until 1894 until the first electric lighting was installed. At first the Hall, Treasury and Library were fitted with electric lights, but tenants in chambers had to make separate applications to The City of London Electric Lighting Company Limited for the installation of electric lighting in chambers. Even after electricity was made available, old methods of lighting persisted in chambers. A newspaper article written about the new electric light on 25 October 1894 reported ‘There are, of course, many who prefer oil lamps to gas, because they believe the light of the former to be better for the eyes. And there are still some who, one the same grounds, prefer candles to oil lamps. There are, I believe, chambers in which no illuminant other than candles has ever been used as a regular thing’.

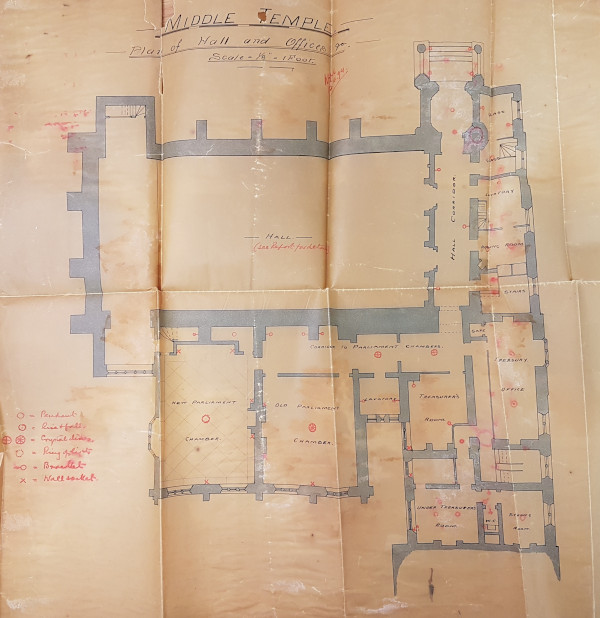

Plan of first electric light fittings in Middle Temple, 12 April 1894 (MT/6/RBW/206)

Tastes regarding lighting levels appeared to alter over time as people became more used to the electric lights. In the early days of its installation, many people found it to be too bright and harsh in comparison to the soft lighting that they were used to. In an 1894 report from a surveyor, it was suggested that any attempt to illuminate the roof of the Hall would ‘be out of keeping with the place’. However, by 8 January 1935 an article Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer reported ‘The Hall of the Middle Temple is not too well lighted. Its flambeaux of electric torches round the walls are made of thick frosted glass and there is no reflection from the roof of black Irish bog oak’. As a result of this sentiment, the Inn decided to install electric lighting on the tables and orange spot lights in the centre of each torch to floodlight the roof in order to better display the Elizabethan architecture at night time.

Photograph of Middle Temple Hall with suspended gas lighting, 1896 (MT/19/ILL/D/D2/8)

Painting by Terence Cuneo of the Joint Bench Dinner held on 20 July 1949, illuminated by electric torches and table lights

Light has completely changed the character of the Middle Temple after dark. Many centuries ago the streets would have appeared dark and sinister – the buildings black silhouettes against the sky, moonlight and the faint glow of candles providing the only illumination. Criminals thrived in these shadowy streets, kept at bay only through the efforts of the watchmen of the Inn, and an uneven paving slab would have presented a significantly greater danger to a midnight wanderer. Work after dark would be limited by the ability of the barrister to buy the candles required to complete it. The limitations of the lighting in these former time periods can provide a greater appreciation for the bright working conditions and safe streets that we enjoy today.