Much like many other historic collections, the Middle Temple Archive contains thousands of items of correspondence - letters and memoranda between the Inn and its members, staff, suppliers and other associates, covering a period of over four centuries and providing an incredibly rich and detailed resource for the study and illumination of all aspects of the Inn's history. This month, we look beyond the content of these items to their context and form - exploring the postal service that brought it to and from the Inn, the global network of epistolary Middle Templars, and the individuals responsible for delivery.

The Royal Mail was established by King Henry VIII in 1516, and became accessible to the public under Charles I in 1635. In those days, letters were not sent in envelopes but simply folded up with the address written on the outside, and often sealed with wax imprinted with the arms or emblem of the sender. Many letters of this nature survive in the archive from the early 1600s onward, including one from William Laud, Bishop of London (later Archbishop of Canterbury), who played a key role in the religious and political struggles of the time which led to the outbreak of Civil War in 1642. His letter, addressed by Laud to 'the right honourable and his worthie frends the Benchers & others the Gentlemen Fellowes of the Middle Temple', is sealed with the arms of the Bishop of London. A letter dated 1744 bears another episcopal seal, that of Thomas Sherlock, Bishop of Salisbury, who had also served as Master of the Temple since 1705.

Letter from William Laud, Bishop of London, to the Benchers and members of the Inn, 10 December 1633 (MT.15/1/TAM/67)

Seal on a letter from Thomas Sherlock, Master of the Temple and Bishop of Salisbury, to the Under Treasurer, 12 June 1744 (MT.15/TAM/159)

The London Penny Post was introduced as a private enterprise in 1680, being taken over by the crown in 1683, and enabled correspondents to send letters around London for one penny (worth about 50p in today's money). Regulations for the Penny Post dating from the late eighteenth century can be found in the archive, addressed to the Under Treasurer. These detail the locations of 'Receiving Houses' around the city where letters could be deposited, reveal that at the time Londoners benefited from six deliveries a day, and list prices and further rules. The document also dictates that bank notes should be cut in half before sending, the second part 'not to be sent till the Receipt of the First is acknowledged'.

Penny Post Regulations, 1 Jan 1797 (MT/1/MIS/22)

By the 1840s, the British postal system, such as it was, was mismanaged, untrustworthy and disjointed. 1839 and 1840 saw a complete overhaul and consolidation of the system, under the aegis of the social reformer Sir Rowland Hill, who had been invited by the government to produce a report. Hill's wide-ranging reforms saw fixed rates established across the United Kingdom, the creation of a government monopoly and various other changes, but the most lasting and influential innovation was the introduction of the world's first postage stamp, the Penny Black, first put into circulation in May 1840. Several examples of the Penny Black from the early months survive in the archive on letters received by the Inn.

Letter to the Under Treasurer stamped with a Penny Black, 1840 (MT.1/PPA)

Pre-paid stamps took off and their popularity quickly spread across the world. However, another innovation introduced at the same time was pre-paid stationery - envelopes and letter sheets, bearing a complex design by the artist William Mulready, which indicated that postage had been paid on the contents. Printed with the image of Britannia and representations of the different parts of the British Empire, these were quickly subjected to public ridicule, and were soon discontinued, unused stocks eventually being destroyed. One example of a Mulready envelope exists in the archive, containing a letter to the Treasurer dated 22 June 1840.

Mulready Envelope addressed to David Pollock, Treasurer, 22 June 1840 (MT.1/PPA)

The Penny Black did not itself last long either, as it quickly became clear that postmarks were difficult to make out on a black background, and was replaced by the longer-lived Penny Red. Similarly, while Mulready's design had been subject to lampoon and mockery, there was still a demand for pre-paid stationery, and the much simpler Penny Pink envelope was introduced. Many examples of both can be found in the archive. The envelope depicted below stamped with a Penny Red is an example of Victorian mourning stationery, printed with black borders to indicate that the sender was in mourning for a lost relative or friend, the thickness of which would decrease as time passed.

Envelopes addressed to William Purdue, examples of the Penny Red stamp and Penny Pink envelope (MT.21/1)

Post reached the Inn from all over the world, demonstrating the global reach of the Inn's membership across Europe, the British Empire and beyond. Postage stamps had been available in British India since 1852, and the volume of mail doubled between 1854 and 1866. In 1859, a barrister paid his bills to the Inn from Allahabad (in modern-day Uttar Pradesh), and the envelope he sent bears a 4 Annas stamp. The Anna was a unit of currency used in India, and the stamp, like those in the United Kingdom, displays the profile of Queen Victoria. The small, fragile envelope was also postmarked Allahabad and Bombay, and annotated 'Via Bombay & Southampton', illustrating its long journey to the Middle Temple.

Envelope addressed to the Treasurer, with a 4 Annas stamp, 1859 (MT.21/1)

Middle Templars also found themselves in continental Europe, and wrote back to the Inn under a variety of circumstances. In 1857, a student of the Inn named Edward Keogh submitted his name for Call to the Bar from Boulogne-sur-Mer in Northern France - then part of the French Second Empire ruled by Emperor Napoleon III. The envelope bears a 40 centime stamp with the Emperor's image.

Envelope addressed to the Under Treasurer from Edward Keogh, stamped with a 40 centime French Empire stamp, 1857 (MT.1/PPA)

Traces of another long-gone empire, the Austro-Hungarian, can be seen in the substantial body of correspondence between the Inn, Henri Perreau de Tourville and representatives of the Imperial government. De Tourville was a Middle Templar who had been imprisoned and convicted by the Austrian authorities for the murder of his wife at the Stelvio Pass, high in the Eastern Alps, and he wrote countless pages from his prison at Gradisca (in modern-day Italy) appealing, ultimately unsuccessfully, against his disbarment and expulsion from the Inn.

Detail from a letter from the prison authorities at the Imperial-Royal Prison at Gradisca (MT.1/PPA)

The sound of the humble letterbox could itself spell danger for a Middle Templar. The Under Treasurer received a note in 1847 from a barrister by the name of Robert Marshall Straight, reporting a particularly alarming occurrence. During the night, 'some mischievous person' had posted lighted pieces of paper through the letterbox of his chambers at 1 Middle Temple Lane - an act 'fraught with danger to the property of the Society'. Mr Butterworth, the proprietor of a neighbouring bookshop, also complained of these 'diabolical attempts' posing risk to his own property, and at the next meeting of Parliament the Benchers ordered that 'the Chief Porter be directed to keep a sharp look out and that the Warders and Watchmen be instructed to do the same'.

Letter from Mr Butterworth to the Under Treasurer concerning attempted arson, 4 November 1847 (MT.21/1)

Postmen themselves appear throughout the Inn's records, not always in a positive light. A letter from one John Adams in Cambridge bears a complaint on the reverse - 'blunder of the postman was not previously delivered'. In March 1855, several postmen from the London District Post Office wrote to the Benchers requesting their 'customary' Christmas Box, which 'through some inadvertancy' had not been received. Christmas Boxes were presents or small sums of money traditionally given to servants and tradesmen shortly after Christmas Day, a practice with roots in the Middle Ages, which gave Boxing Day its name. Tradition notwithstanding, the petition was rejected at the next meeting of Parliament.

Letter from the postmen of the London District Post Office to the Under Treasurer, 24 March 1855 (MT.1/PPA)

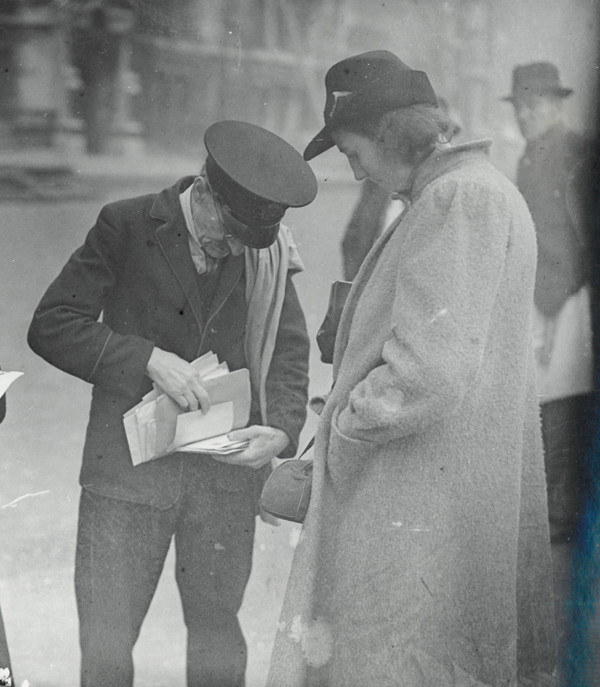

Following the revolutions it saw in the nineteenth century, the postal service continued to supply the Middle Temple, its residents and staff with letters and parcels throughout the twentieth century, including during some of the Inn's most dramatic periods. A photograph from early 1941 shows a postman delivering letters in the Inn just weeks after the devastating bombing raids of late 1940 which destroyed or damaged so many of the Middle Temple's buildings.

Photograph of a postman on his rounds in the Inn, 2 January 1941 (MT.19/PHO/10/11/13)

The archive contains countless examples of personalised letterheads and writing paper - including those of Buckingham Palace and both Houses of Parliament. One less grand but uniquely charming twentieth century example is found on a letter sent to the Librarian in 1950 by a member of the Inn. His address was a yacht moored at Woodbridge in Suffolk, and his very thoughtful letterhead included a detailed, hand-drawn map which illustrated just where his floating home could be found.

Detail from a letter from R.C. Northcote to the Librarian, 8 July 1950 (MT.3/CPA/39)

While post continues to arrive in considerable quantities from its still global network of correspondents and is ably distributed by the Front of House staff, twenty-first century communications are nevertheless much changed. A great deal of day-to-day correspondence now takes place by email, messaging services and social media - presenting the archive with a modern day challenge to ensure the capture and continued preservation of the rich archival resource that such communications represent.