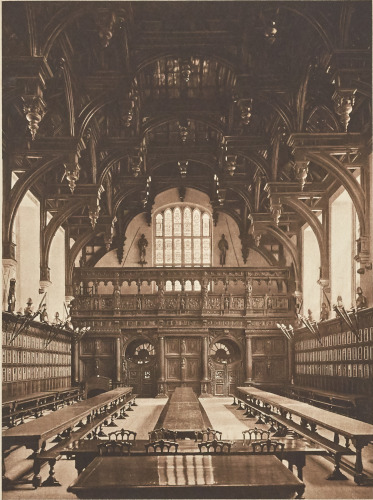

The screen at the east end of Middle Temple Hall, c.1937 (MT/19/ILL/D/D2/21)

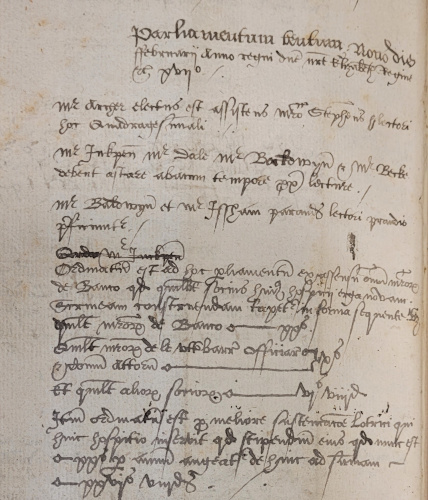

In terms of its architecture, the Middle Temple is best known for its beautiful Elizabethan Hall, completed in 1573. The Hall has many interesting features, but the east end of the space is dominated by its beautifully carved screen with a musicians’ gallery above. This screen was completed within a few years of the construction of Hall and was paid for with contributions from the membership. Like the rest of the Hall, no documentation survives, besides the Inn’s Minutes of Parliament, recording its construction and there is no information about the mysterious designer and craftsmen behind the creation of its fascinating wood carvings. Its story is made more compelling still by the fact that if it were not for the good sense and determination of the Inn’s membership and staff, it would not be here today.

Order for financial contributions towards the new screen, 9 February 1575 (MT/1/MPA/3)

The original purpose of the screen can be deduced by comparing it to other buildings of the period. The design of Middle Temple Hall followed the traditional medieval form in its plan - it was constructed as a large communal space with a raised platform at one end, a large central fireplace, and a ‘screens passage’ at the entrance way that was separated from the rest of the Hall with an ornately carved screen. The screens passage provided a discrete way for servants to move from the service area opposite the Hall that housed the buttery – this is where beer and bread was stored and distributed. It is possible, though not certain, that the entryways into the main Hall could be further screened off with curtains, as receipts during the mid-seventeenth century show that curtains and hangings were generally present in the space during this period. This would have shielded the Hall from the hustle and bustle in the passageway and reduced draughts coming into the large, already chilly space. The Hall’s exterior entranceway is orientated northwards, and it was possibly constructed in this manner to catch the fresh northern winds, which were believed by contemporary architects to purge the air of foul, sickness-inducing miasmas.

Plan of Middle Temple Hall, c.1920-c.1940

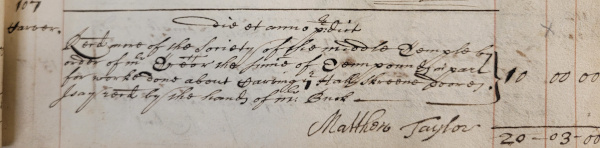

The doors were only added to the Hall screen in 1671 and shortly after an incident of poor discipline on the part of some of the membership. At the beginning of the 1660s, the festival of Christmas had been re-instated after its ban during the Commonwealth. Many orders were made by the Inn’s Parliament forbidding a grand or gaming Christmas, but during Christmas 1670, those were most outrageously broken. Twelve members were fined £20 each, a huge sum at the time, ‘for breaking open the doors of the Hall, Parliament Chamber, and kitchen at Christmas, and setting up a gaming Christmas, persisting after Mr. Treasurer’s admonition, and continuing the disorders until a week after Twelfth day’. In the same session as these gentlemen were fined, the Inn’s Parliament ordered that ‘Doors shall be made to the screen in Hall’. This allowed the securing of the Hall against intruders while still allowing access to the passage to members whose chambers adjoined the Hall or were nearby in the garden.

Receipt for money paid to Matthew Taylor, carver, for making the screen doors, 1671 (MT/2/TRB/29)

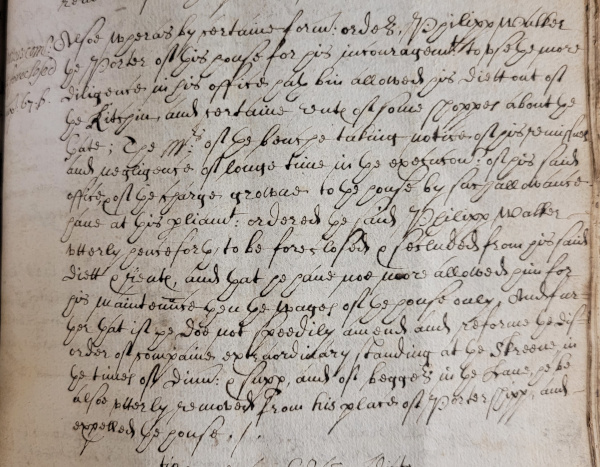

This use of the screen as an additional barrier to entry into Hall can be seen on many occasions in the seventeenth century. A Butler or Under Butler was usually stationed at the screen to maintain the discipline of the company and to police entry into the Hall. The importance of this presence was shown in 1624 when the Porter was severely reprimanded for remissness in his duties leading to ‘company extraordinary standing at the screen at dinner and supper’ – the precise nature of these loiterers is unknown, but it is possible that they may have been in search of leftovers as it was usual to distribute these to the poor after a household or company had eaten its fill. As well as barring entry, the officers stationed at the screen also attempted to prevent the exit of miscreants so that they could be formally detained – sometimes unsuccessfully as in 1610 when Gyles Garton struck another member over the head with a knife and ‘rescued himself at the screen from the Butler who had him in charge by Mr. Recorder’s warrant’.

Order of Parliament regarding ‘company extraordinary’ standing at the screen during meals, 26 November 1624 (MT/1/MPA/4)

The creation of the screens passage by splitting the Hall space with a wooden screen had the added effect of allowing the creation of an elevated floor or ‘gallery’ above. Here groups of musicians could play without being in the direct line of sight of revellers and allowed the space below to be optimised for dining and revelry. The Middle Temple frequently hired musicians to play for their annual feasts and celebrations, and on one occasion in 1613 hired the famous lutenist John Dowland to play with fellow musicians on Candlemas Day.

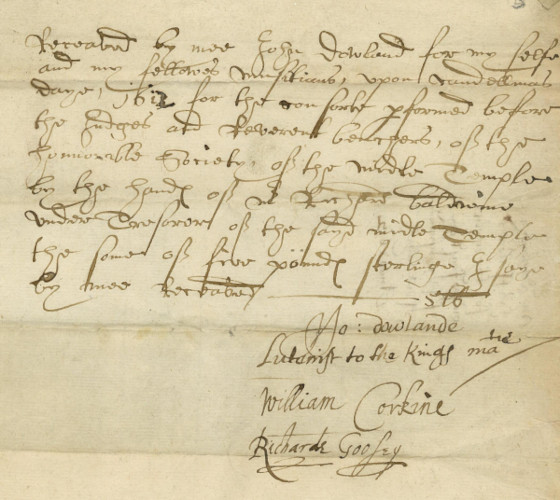

Receipt signed by lutenist John Dowland for music performed on Candlemas Day, 1613 (MT/7/ERB/2)

An unexpected function that the screen served was as a public noticeboard. From the early seventeenth century, before the circulation of newsletters among the membership, the screen would be the place in which important notices were placed for public viewing. These would include orders of the Inn’s Parliament, general notices and lists of members seeking to be Called to the Bar. This process was known from the early eighteenth century as being ‘screened’ and allowed the Benchers and the Membership to know the names of the Students requesting Call so that concerns could be raised over any unsuitable candidates – this may be related etymologically to the modern process of ‘screening’ candidates.

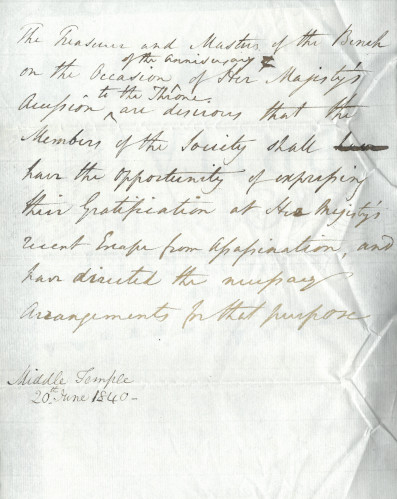

Draft notice screened in the Hall on the anniversary of Queen Victoria’s accession to the throne mentioning the assassination attempt on her life, 20 June 1840 (MT/21/1/103/6/22)

The screen in Middle Temple Hall, while it stood in place for centuries and bore witness to the revels and great happenings of times past, would not be with us today if not for the great pride that past Middle Templars took in the Society’s history and their determination to preserve it for future generations. World War Two was extremely destructive to the Inns of Court, and though Middle Temple Hall survived, in contrast to Inner Temple Hall, it sustained a great amount of damage. On 15 October 1940, one of the most destructive nights of the war for the Society, a bomb, or ‘land mine’, fell near the east end of Hall, destroying three blocks of chambers. A huge piece of masonry from Elm Court was hurled across Middle Temple Lane and hit the east gable of the Hall. The wall was blown inwards and consequently the gallery and screen were smashed to pieces and buried under rubble.

Painting entitled ‘Armistice Day’ by Frank E. Beresford depicting the rubble strewn east-end of Hall, 1941

The aftermath of the devastation is brilliantly captured in a painting by Frank Ernest Beresford, which currently hangs in the musicians’ gallery. Beresford was well known at the time for his interior paintings and gained prominence for his depiction of the Royal Princes keeping vigil over the body of King George V within Westminster Hall. After hearing of the bomb damage to Middle Temple Hall, Beresford wrote to the Treasurer. Sir Cecil Hurst KC, asking for permission to produce a small oil painting as ‘I am so distressed to see of this damage to such a beautiful and historic Hall’. There was considerable press interest in the painting by such a well-known artist and Beresford had to work quickly to finish before the debris was cleared away. He was very pleased with the result, calling it his ‘best work’ at the time, and presented the preliminary sketch to the Inn. The painting itself was purchased by the Society in 1964.

Middle Temple Hall at the start of its clean-up operation, November 1940 (MT/19/PHO/4/2/9)

Despite the catastrophic destruction to the east end of Hall, the Inn’s Surveyor, Mr C. Swanson, had the presence of mind to rescue as many pieces of the screen from the ruins as possible. After a crew of volunteer workmen picked their way through the rubble, over 200 sacks were filled up with fragments of wood. These were sent off to Ludlow in Wales to be put into storage with the High Table and Cupboard, which had already been safely sequestered away.

Photograph of workmen salvaging pieces of the screen in Middle Temple Hall, 16 October 1940 (MT/19/PHO/4/3/1)

After the war, the painstaking work of reconstruction could begin. Between the years 1948-1950, the fragments of the Elizabethan screen were pieced together under the direction of the Inn’s architect, Edward Maufe. Fortunately, James St. Aubyn, the Inn’s architect during the second half of the nineteenth century, had created a scale drawing of the screen that included sectional elevations and showed the carvings in detail. This drawing proved to be of vital importance to the workmen and they had a framed version of it stood up in their workshop to be used as a constant reference. This helped not only in piecing together the fragments like a gigantic jigsaw puzzle but also assisted the craftsmen in spotting when a piece of the screen was missing, reducing the need for guesswork in identifying parts in need of replacement.

Photograph of craftsmen reassembling the screen using a nineteenth century architectural drawing as a reference, c.1950 (MT/19/PHO/4/3/14)

Although St. Aubyn had been meticulous in recording the detail of the front of the screen, no record existed of the construction of the back. The reconstruction was forced to use a design newly created by Maufe, who designed it to be ‘in harmony with the rest of the screen’ and the new gallery was constructed using new British Columbian pine. Fortunately, craftsmen were able to reconstruct most of the screen using the original oak pieces, though there were some parts that could not be recovered. Instead of using new wood to remake the destroyed pieces, the craftsmen used wood salvaged from a 700-year-old barn in Rainham, Essex, and debris from the shattered east bay of the Hall roof.

Fragment of the Hall screen, left over and given to G.E. Cassidy who worked with Edward Maufe during the postwar period, and later donated to the Inn (MT/20/118)

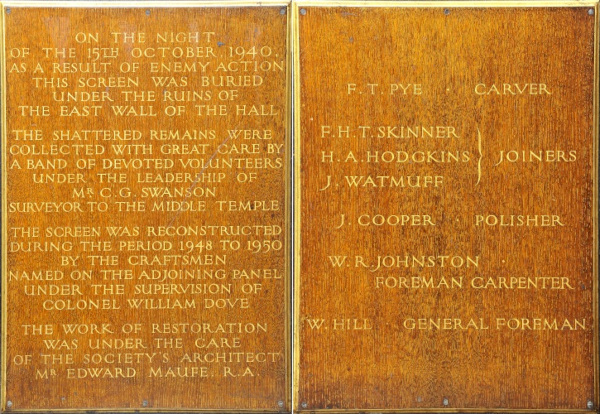

After the restoration of the screen, it once again stood pride of place at the east end of Hall. In recognition of the great achievement of the craftsmen for this demanding feat, the Benchers erected a plaque commemorating the names of the Surveyor, Consultant Architects, contractors and individual craftsmen involved in the project in the screens passage – a measure to immortalise those responsible for ensuring the survival of this historic piece of architecture for the enjoyment of the present and future membership of the Middle Temple.

Photographs of the plaques commemorating those involved in the restoration of the Middle Temple Hall screen