As the only surviving gateway to the City of London, Temple Bar once stood at the intersection of Fleet Street and the Strand, overlooking the perpetual flow of traffic and pedestrians traversing the heart of historic London. Many Middle Templars would have passed through this gateway during its time there, as the Inn is just a stone's throw from the boundary of the City. This long association has led to elements of the structure’s storied past, particularly its lengthy return journey to London, being preserved in the Inn’s Archive, despite not being itself a part of Middle Temple.

Painting depicting the east side of Temple Bar, with Middle Temple gate on the left, c.1730 (P.251)

Although, over the centuries, several different structures existed at the same location to mark the City boundary, the ‘Temple Bar’ that is most known is the one built after the Great Fire of London in 1666. This structure was designed by the illustrious architect Sir Christopher Wren, who would later take part in the reconstruction of Middle Temple gate as a surveyor. Wren’s design is a two-storey stone arch featuring statues of members of the royal family on both sides of the facade, with a central arch for traffic and two smaller arches for pedestrians on each side – an example of English Baroque architecture pioneered by the architects of the day.

Standing at a significant juncture in central London, this iconic 17th-century structure has witnessed numerous important events throughout the city’s history – from ceremonial processions to public turbulence. For centuries it has sat along the royal family’s processional route into the City of London, often draped with bunting and ceremonial decorations on such occasions. This tradition persisted well into the 20th century, long after the gateway was removed and replaced by the current pedestalled Temple Bar Memorial in the late 1870s.

King George V and Queen Mary passing through Temple Bar Memorial on their way to St Paul's Cathedral to attend a Thanksgiving service, as part of the celebration of the King’s Silver Jubilee, May 1935 (MT/19/ILL/F/F7/10)

One early illustration in the Archive, however, depicts it as the battlefield of a riot in 1769, when some 600 City merchants supporting the government of King George III were attacked by a mob during their march to St James’s Palace. The loyal supporters, shattered and covered in dirt, had to seek shelter in the Nando’s Coffee House, which operated near the Middle Temple gate. A subtle reminder of its hideous history can be spotted at the top of the illustration, where two ‘talking heads’ are set on the spikes on top of the main arch – like London Bridge, Temple Bar was once used by the monarch to exhibit the heads of traitors as a gory warning to potential perpetrators during the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Battle of Temple Bar, published in The Gentleman's Magazine, March 1769 (MT/19/ILL/F/F7/1)

Beyond the glorious and gruesome, the area around Temple Bar was known as a vibrant neighbourhood to the public. Banks, news agencies, printing offices and coffee and cigar houses thrived, drawing people from all walks of life to the area. Child & Co., one of the UK’s oldest private banks (of which the Inn was a long-time client), started off from a Goldsmith’s business near the structure. A mid-19th century illustration captures Temple Bar’s lively ambience, depicting Londoners bustling about, some carrying large advertising billboards – a popular novelty at the time – while passing by the shopfront of a time-honoured fishmonger next to the gateway.

Illustration depicting a fishmonger next to Temple Bar, published in The Last of the Bulk Shops, Temple Bar, c.1850 (MT/19/ILL/F/F7/6)

Postcard of a print depicting the happenings around Temple Bar, published in Original Views of London as it is by Thomas Shotter Boys, c.1840 (MT/5/TSE/26)

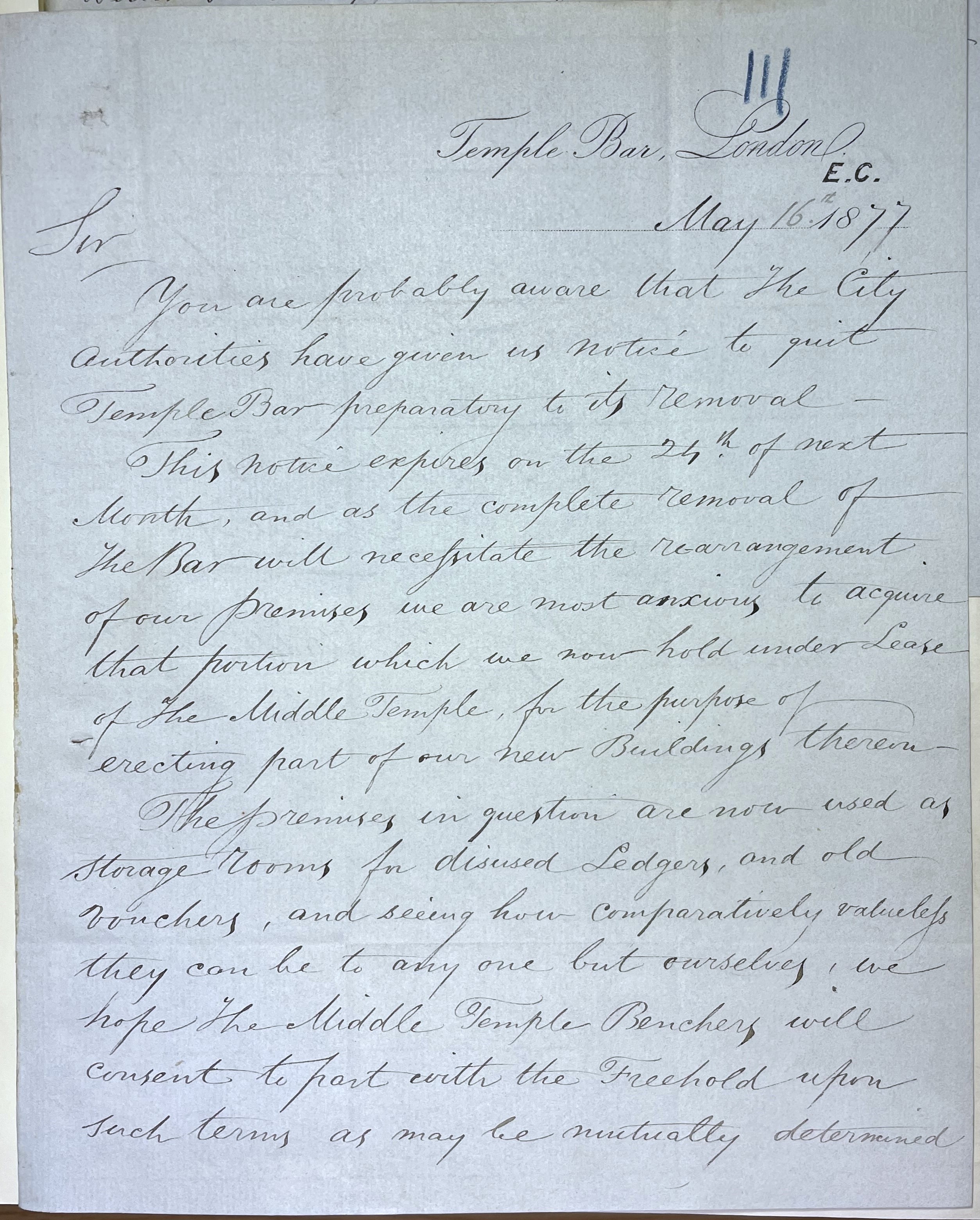

But the ever-expanding activity around Temple Bar meant this symbolic piece of architecture gradually came to be seen as an impediment to city planning, which finally led to the City’s decision to demolish it to make room for easier traffic and the construction of the Royal Courts of Justice. The impact of this is indirectly reflected in a letter to the Inn from Child & Co., the tenant of the upper space of Temple Bar. With the removal of the structure necessitating rearrangement of their storage, the bank wrote about their anxiety to purchase certain other premises, which at that point they leased from the Inn for storage, on which to erect new buildings.

Extract of Child & Co.’s letter to the Treasurer regarding the purchase of the Inn’s premises for storage, May 1877 (MT/1/PPA)

The structure was eventually dismantled in January 1878, with each stone painstakingly numbered, and subsequently sold to Sir Henry Meux and his socialite wife Lady Valerie Meux and rebuilt in Theobalds Park, Hertfordshire, where it was used for entertaining guests including our Royal Bencher the Prince of Wales. In the years which followed, several proposals to return Temple Bar to the City of London emerged, but all met with failure.

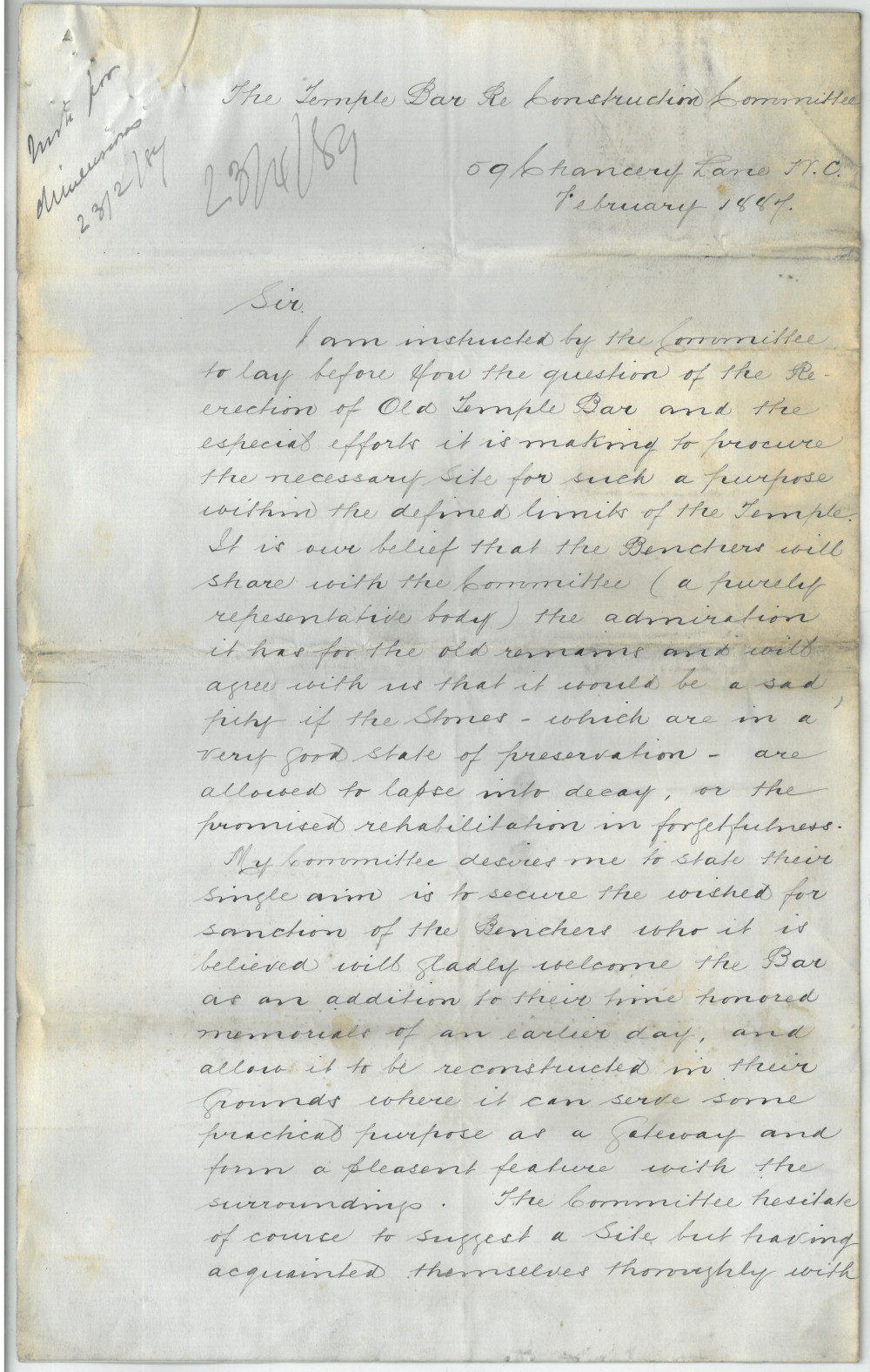

One of the first attempts came in 1887, when the Temple Bar Reconstruction Committee submitted a report to the Inn recommending the structure's relocation to the head of the steps in Fountain Court. The then Master of the Temple, Charles Vaughan, was a member on the committee, alongside several MPs and architects. This connection, however, didn’t seem to have been favourable in convincing the Inn, and reply was ordered that the Benchers ‘[regretted] to be unable to find a site’ for the relocation.

Extract of a report submitted by the Temple Bar Reconstruction Committee, February 1887 (MT/5/TSE/37)

The relocation quickly became a topic of public interest as well. Just one year later, the British illustrator Henry Brewer wrote in The Graphic that Temple Bar ‘would have grouped well with Mr Berry’s new buildings [Temple Gardens], providing a far more dignified approach than the present iron gates and diminutive lodge’. Brewer, famous for his depiction of city panoramas, supported his claim with a beautifully executed illustration, picturing an imagined scene of the structure situated in front of the newly built Temple Gardens and adjacent to the Inn’s now lost Victorian library.

The Proper Place for Temple Bar, an illustration by Henry Brewer published in The Graphic, February 1888 (MT/19/ILL/F/F7/9)

Brewer’s suggestion, as we now know, was never realised, but it lingered on and the Embankment entrance to Middle Temple remained the strongest candidate for relocation for many decades. In 1921, the London Society, founded by the renowned architect Aston Webb who would later carry out repair work for Middle Temple Hall, took over the relocation plan. The society tested the waters but was met with a somewhat lukewarm response from the Inn, who said they would give ‘sympathetic consideration’ to the proposal.

The next attempt to relocate Temple Bar for which evidence survives in the Archive was in June 1939, this time initiated by Lord Justice MacKinnon, with an estimated relocation cost of £2,000. The Inn appointed a special committee to discuss this matter with Inner Temple, but no further mention to this can be found in the minutes of Parliament. Given the looming threat of war, it is understandable that the Benchers might not have prioritised the fate of an external piece of architecture over other pressing matters facing the Inn.

After the Second World War, interest in Temple Bar was revived internally by Master James Cassels, who, having seen the structure in person during a trip, described it in a letter to the Treasurer as magnificent and 'a splendid thing’ to have in the Inn’s garden. Finding the relocation impracticable and financially unjustified, Parliament was originally not sold on the idea. But soon the active involvement of the City Corporation in the game seemed to have given the Inn confidence that the plan was not out of reach.

Extract of Master James Cassels’s letter to the Treasurer, November 1948 (MT/5/TSE/24)

Apart from the various correspondence between the Inn and the City Corporation, the changing attitude of the Inn can be gauged in a draft letter co-signed with Inner Temple to The Times in April 1950. While setting out the technical and statutory challenges to be surmounted, they nonetheless expressed their willingness to accept Temple Bar and to be jointly responsible for its preservation and maintenance. With half of the relocation expenses covered by the City Corporation committees, the post-war relocation plan emerged as a very promising one.

Extract of a letter co-signed by Middle Temple and Inner Temple to The Times regarding their position in the relocation proposal, 1950 (MT/5/TSE/24)

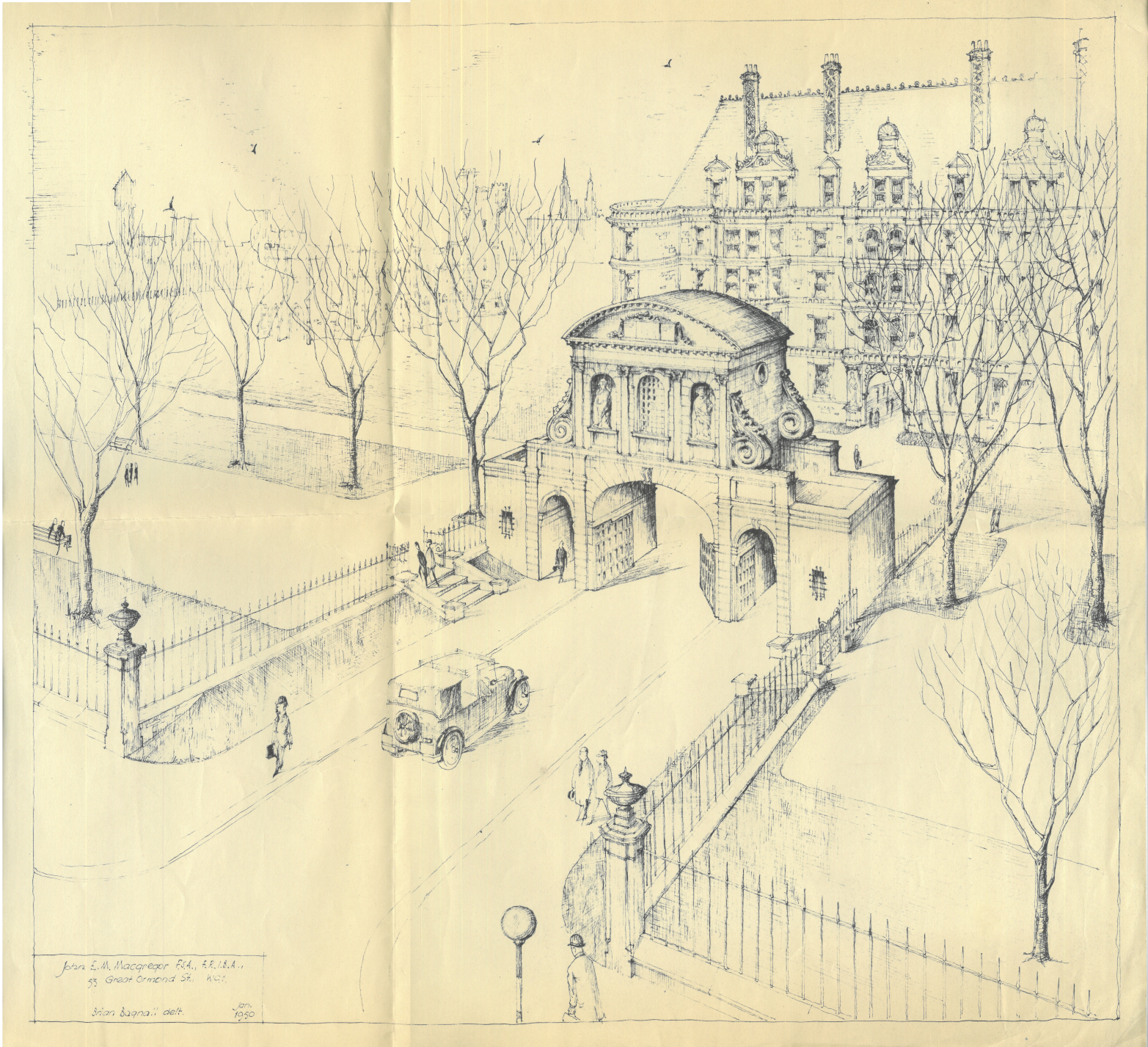

The relocation plan was fleshed out in much detail, including a report on siting, structural treatment, costing as well as several architectural plans produced by John MacGregor, the architect advising the City Corporation. There is also a letter from Banister Fletcher, surveyor to the two Inns, outlining his views in favour of the proposed site in Middle Temple Lane. The relocation, he wrote, would be ‘a great delight to many’ after the destruction of so many City buildings by the enemy.

Architectural plan by John MacGregor showing Temple Bar’s relocation to the Embankment entrance to Middle Temple Lane, January 1950 (MT/5/TSE/24)

The plan, however, didn’t go ahead as planned – the main reason being the refusal of the then Ministry of Housing and Local Government to give the green light. Contrary to the opinions of many City architects and surveyors, the Ministry believed that Temple Gardens, being a large 19th century building, would form ‘a most unfortunate setting for Temple Bar’.

Several decades passed before another relocation plan was considered viable. Since the late 1970s, the Temple Bar Trust, founded by the former Mayor of London Sir Hugh Wontner, spearheaded a decades-long effort for relocation with funding support from the government and figures in US legal circles, which finally succeeded. While there were discussions within the Inn about Middle Temple Lane being a more preferrable location than the structure’s eventual location near St Paul’s, the idea never went further than a preliminary enquiry this time.

Drawing picturing Temple Bar’s relocation to the Temple Place entrance to Middle Temple, c.1970s-1980s (MT/5/TSE/26)

Whether the Embankment entrance to Middle Temple Lane would have indeed been a proper site for Temple Bar is something we will probably never know for sure. While the structure’s present location is far removed from the City boundary – which might be considered contradictory to its symbolic significance – the very existence of it within the City of London after more than a century of displacement is something we can all appreciate.