To follow last month's 'Archive of the Month' on all things culinary, this month's edition looks at wine, beer, liquor and their consumption at the Inn. A wealth of material in the archive records the drink supplied to and kept at the Middle Temple over the centuries, how much was drunk (and by whom), as well as its ill-effects on members and staff alike.

One of the earliest references to the consumption of drink by Middle Templars appears not in our archive but in that of Lincoln's Inn. The first of the Lincoln's Inn 'Black Books' records, on 14 March 1442, a payment of forty-nine shillings and fivepence for a 'drinking' between the Two Inns - in Latin, 'pro potacione inter Hospicium de Lyncoln ynne et Hospicium Medii Templii'.

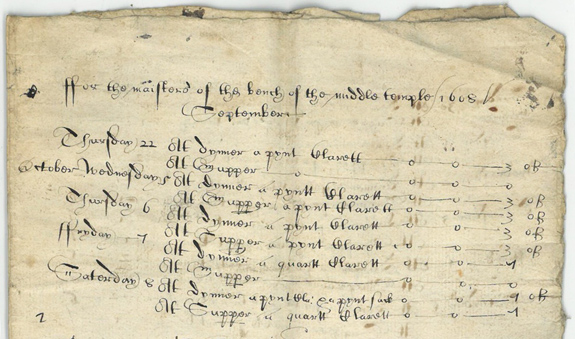

The Wine Butler's accounts and 'Consumption Books' provide a comprehensive daily record of the quantity and variety of drinks consumed by the Benchers and barristers between 1608 and 1944, and are a fascinating window on how tastes and habits have changed. In October 1608, according to one of the earliest such records, the Benchers seem consistently to get through a pint (if not a quart) of claret at dinner and another at supper.

Record of wine for the Benchers in September and October 1608 (MT.7/WBA/1)

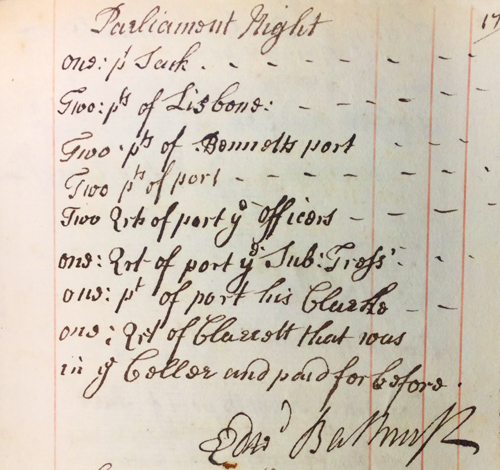

Tastes diversified in the following century. For example, one Parliament night in 1743, the account records the consumption of one pint of 'sack' (a white fortified wine imported from Spain and the Canaries), two pints of 'Lisbone' wine (wine imported from Lisbon), two pints of Bennett's Port and two of regular port, as well as, specifically, a quart of port for the Under Treasurer and a pint for his Clerk. The predominance of port in British cellars was thanks in part to long-running conflicts with the French in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries limiting the import of French wines.

Wine consumed on Parliament Night, May 1743, Wine Butler's Account Book (MT.7/WBA/238)

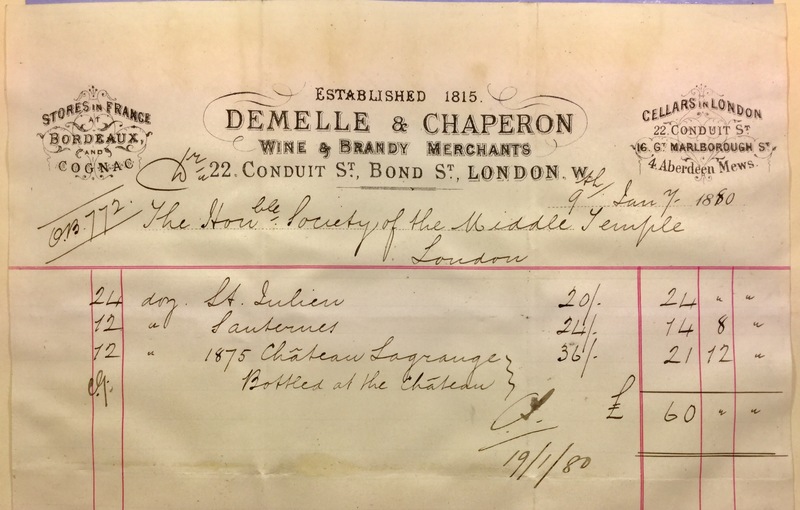

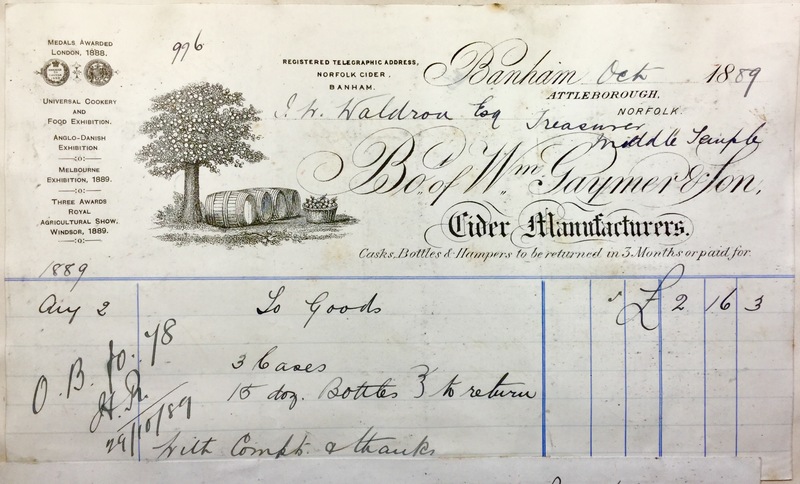

By the nineteenth century, the lists start to sound more familar to the modern ear - and more luxurious - including champagne, claret and Sauternes, as well as cognac and Scotch whisky. Indeed, these developing tastes in drink at the Inn are also represented in the Treasurers' Receipt Books of the day, which contain receipts and bills, often quite ornately decorated, for consignments of drink from a range of vendors and traders. In January 1880, for example, Demelle & Chaperon, Wine & Brandy Merchants of Bond St supplied the Inn with St. Julien, Sauternes and 1875 Chateau Lagrange (bottled at the Chateau). In 1889, William Gaymer & Son of Banham, Norfolk were sending cases of cider, and John McGregor & Son of the Balmenach Distillery supplied whisky by the cask.

Bill for wine from Demelle & Chaperon Wine & Brandy Merchants, Treasurer's Receipt Book 1880 (MT.2/TRB/243)

Bill for cider from William Gaymer & Son, Cider Manufacturers, Treasurer's Receipt Book 1889 (MT.2/TRB/252)

Bill for Scotch Scotch Whisky from John McGregor & Son, Distillers, Treasurer's Receipt Book 1889 (MT.2/TRB/252)

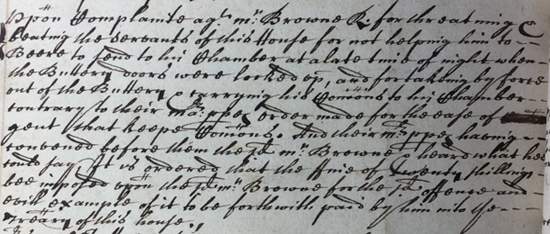

Drinking has, inevitably, led to controversies and disruptions at the Inn over the years. In 1695, one Robert Browne was fined twenty shillings by Parliament for 'threatening and beating the servants of this House for not helping him to Beere to send to his chamber at a late time of night when the Buttery doors were locked up'. Such incidents were not uncommon in the seventeenth century Inn, and Browne himself was guilty of more than one such offence.

Order of Parliament concerning Robert Browne's misdemeanours, Minutes of Proceedings of Parliament 1658-1704 (MT.1/MPA/6)

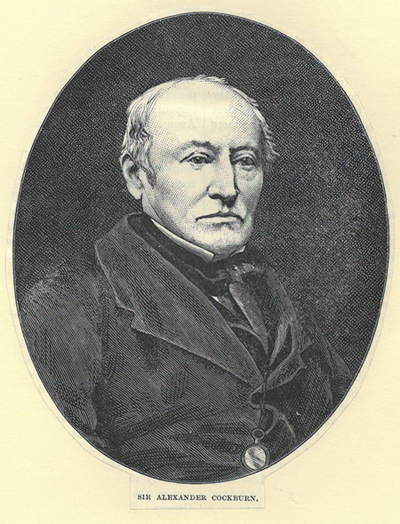

Richard Paternoster, whom we met last month complaining about soup, had opinions to air the following year on the supply of wine at dinner. In early June 1856, he wrote to Sir Alexander Cockburn, the Treasurer of the day, complaining that the 'silly, absurd custom' of not serving wine to senior barristers on Call Days 'ought to be abolished'. Men, he pointed out, 'cannot be expected to dine without wine'. In a similar missive to the Under-Treasurer, he added that he and his fellow diners considered this 'a great hardship'. Cockburn and his fellow Benchers were unmoved: at a Parliament held later that week, they decided to decline Paternoster's request.

Sir Alexander Cockburn, Treasurer 1856 (MT.19/ILL)

The choice of wines for purchase and consumption at the Inn was, of course, an immensely important matter, and one in which the Treasurer himself was often a prime mover. The Treasurer's claret tasting notes from November 1880 survive in the Archive, and include his jotted down opinions on a range of vintages and varieties. Some of these are 'very good', others 'will never be better' and one, a Pape Clement Demelle, he considers 'too good for Hall', a sentiment which might have given Richard Paternoster something to say.

Treasurer's Claret Tasting Notes, 1880 (MT.7/WIR/93)

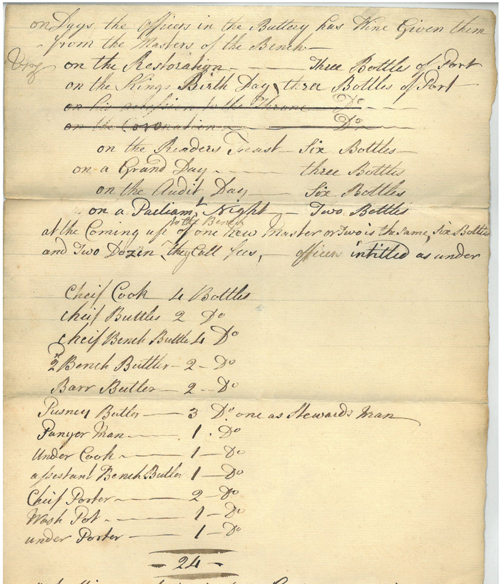

It was not only barristers, Benchers and students who enjoyed the contents of the Inn's well-stocked wine cellars. A document from the late eighteenth century gives clear instructions as to the quantities of wine to be given to certain officers in the buttery on occasions such as Grand day, the King's Birthday, the Restoration of Charles II and Audit Day.

Instructions regarding wine given to Officers in the Buttery (MT.8/SMP/109)

Problems did, however, arise when staff drank too deeply from the Inn's supplies. In 1856 the Warden, one Charles Inge, was found drunk and insolent, and had to be put out of the gate into the hands of the City Police. Later, Henry Beresford-Pierse, Under-Treasurer from 1913-1930, was forced to take measures to eliminate drunkenness among the staff. The department of Porters and Warders, he noted in a report to the Treasurer in 1914, he had 'found in a condition of complete chaos, the head porter an habitual drunkard'. While satisfied with his progress here, he nonetheless found it necessary twelve years later to post a notice to the 'outside staff' reminding them that they were not to be found in the kitchen, buttery or pantry, nor to receive any drink there, on pain of dismissal.

Order forbidding access to the kitchen, buttery and pantry (MT.8/SMP/184)

Once again, the Inn's historic collections intersect with this month's theme. In the silver vaults, there is a fascinating collection of 28 wine labels, metal badges made to hang around the neck of a decanter or bottle, identifying claret, Madeira, port and other wines. Some of these, given to the Inn in 1961 by Master Eric Sachs (the first Master of the Silver), are elaborately decorated with bacchanals, satyrs and boars' heads, and some date from as early as 1775.

Collection of 28 wine labels, donated by Master Eric Sachs

The Inn used to bottle its own port directly from the cask, into 'branded' Middle Temple bottles which bore the Lamb & Flag emblem. Two of these were donated to the Library by Paul Powlesland, and can be viewed, alongside a range of other interesting artefacts, on the second floor landing of the Ashley Building.

Port bottle with Lamb & Flag emblem

The familiar lead cistern in the Bench corridor, dating from the reign of James I, was at one point in its long time at the Inn used as a wine cooler. The oaken lids of the cistern are said to be the last remaining peices of wood from the old Temple Bridge, the pier at the end of Middle Temple Lane which was said to date from the days of the Knights Templar.

James I lead cistern with later oak and brass-banded lids

While tastes and quantities have changed over the years, the Inn continues to supply fine wines, beers and spirits (including, in keeping with tradition, Middle Temple Port) at lunch and dinner, and indeed at the popular wine tasting events. Enjoy responsibly!