The role of Steward, well-established in English history, was traditionally one of great responsibility, encompassing the management of a master’s estate, household and other affairs. This position was comparable to that of the Under Treasurer at the Middle Temple, where the role of the Steward himself was more limited in scope, revolving primarily around the provision of food for commons and pursuing payment from members for the aforesaid. Despite the more limited nature of the role, its responsibilities were of sufficient importance that, next to the Under Treasurer, the Steward was the most senior and best paid servant at the Inn between c.1500-1747.

The provision of commons, communal meals for the membership, by the Steward was very important to the social life of the Society. It was considered that ‘… the good estate of the House depends upon public commons’ and was noted in 1644 that previous Governors had ‘specially been employed in holding together in commons the company of this Fellowship in their public Hall, as a thing wherein principally consisted the common honour, and the peculiar good of every particular member, and without which a company so voluntarily gathered together to live under government could hardly be termed a Society’. Attendance at commons was also important for educational reasons as exercises were performed after dinner, and after supper until supper commons were abolished in 1724, under the supervision of Masters of the Bench during Term and Masters of the Bar during Vacations.

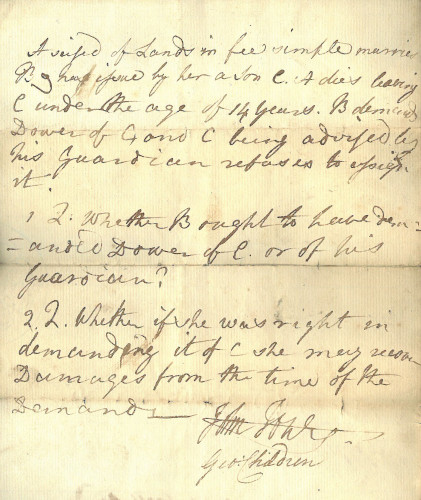

Record of a Candle Exercise relating to the demand of a dower, 1768 (MT/21/1/28/VI/2)

Due to the educational and social importance of commons, attendance was made mandatory by an order of Parliament dated 12 November 1556 that stated ‘every one of the Fellowship, being in health, if he lie in his chamber, shall be in commons, except Benchers and such shall have special licence of the whole Bench…’. On 5 May 1581, this requirement was reduced to eight weeks out of the year on penalty of forfeiture of chambers for non-attendance. Some exceptions were granted to this rule, such as to Peter Frechvile and John Darcye in 1595, who petitioned Parliament for a reprieve from being in commons due to having ‘great affairs in the country and far dwelling’.

Print of Benchers and Members taking Commons in Middle Temple Hall, c.1840 (MT/19/ILL/D/D2/1)

Rules regarding the attendance at commons were tightened during and after the English Civil War (1641-1652). During the conflict commons were abandoned and on 13 April 1649, Parliament noted ‘how prejudicial the present discontinuance thereof is’. In response to the discontinuance, former orders relating to commons were amended include the obligation that ‘every gentleman having a chamber or part of a chamber shall be in commons one whole week every term at least, or in default be cast in commons of the House for a whole week in this term and every term succeeding, that those present shall pay commons weekly beforehand, and if absent within a fortnight after each term’. On 24 January 1667/68, this requirement was raised to two weeks a term, one of those being the termly Grand Week. It was at this time that it was made a qualifying condition for Call to the Bar that candidates be in commons two whole weeks every term for a period of two years.

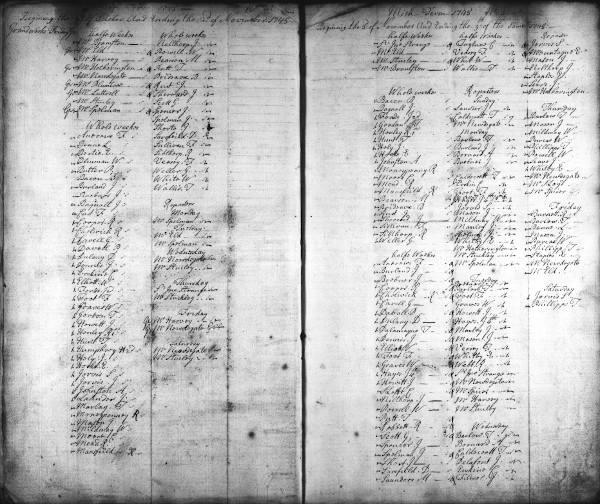

Buttery Book record of gentlemen dining in Hall for the week beginning 27 October 1745 (MT/7/BUB/1)

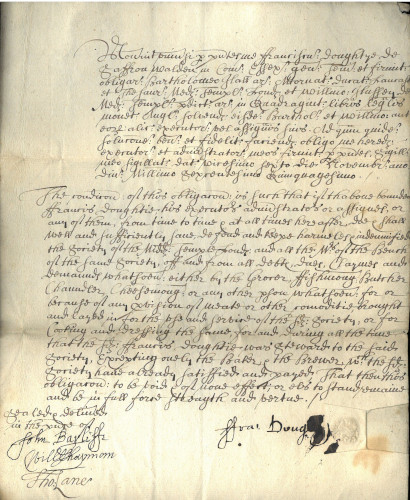

Attendance at commons was mandatory for a set amount of time per year, but many gentlemen appeared to be reluctant to pay for this part of the Inn’s communal life. It was the job of the Steward to cajole members to pay and to enforce their being ‘cast out of commons’ if they failed to do so, cutting them off from the community and education of the Inn. The nature of the early modern economy made the retrieval of this money all the more vital for the Steward. Lack of access to sufficient fiat currency and no access to banks by the majority of the population meant that the everyday economy functioned on credit and people would run up tabs with their local tradesmen. The Steward was personally indebted to the tradesmen who supplied the Inn and could be sued by law for payment. In order to help ensure that tradesmen received payment, it was ordered on 29 October 1613 that ‘John Bull, now Steward, shall enter into bond with sureties for the discharge of debts due to the baker, brewer and others who serve the house with provision’. All subsequent stewards had to provide the names of two sureties when they took up the position, and these gentlemen would be liable for any of the Steward’s unpaid debts. However, the debts accrued by the Steward on behalf of the Society often exceeded the value of the bond.

Bond of obligation of John Doughtye, Steward, indemnifying him against any debts owed to the Grocer, Fishmonger, Butcher, Chandler of Cheesemonger, 26 November 1650 (MT/21/2/7/JA)

Unpaid debts to the Steward for commons were a recurring problem throughout the history of the Inn. In the time of Henry VIII there were no guarantees for payment by members for debts. According to a report on the Middle Temple, ‘if any of the fellowship be indebted to the house… he shall openly in the Hall be proclaimed; and whosoever will pay it for him, shall enjoy and have his lodging and chamber that is so indebted’. This method of extracting payment would prove ineffective and on 21 June 1577, Parliament ordered that ‘Every gentleman of the house shall be bound with two sureties for the payment of commons to the Treasurer’. This practice continued for centuries, with students providing the name of two sureties on admission to the Inn to ensure that their debts would be paid. The names of these sureties, written on a student’s ‘bond’, can often provide interesting information about a member’s connections in society and the law.

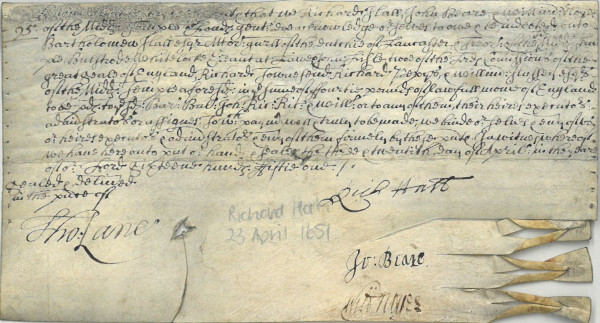

Bar bond of Richard Hall, admitted to the Inn on 23 April 1651 (MT/3/CBB/1)

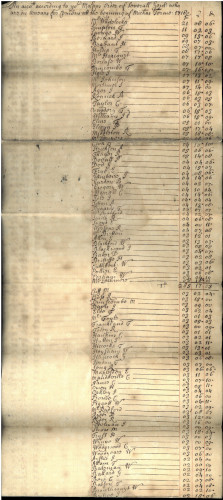

Account of gentlemen in arrears for commons, Michaelmas 1718 (MT/7/CAS/7)

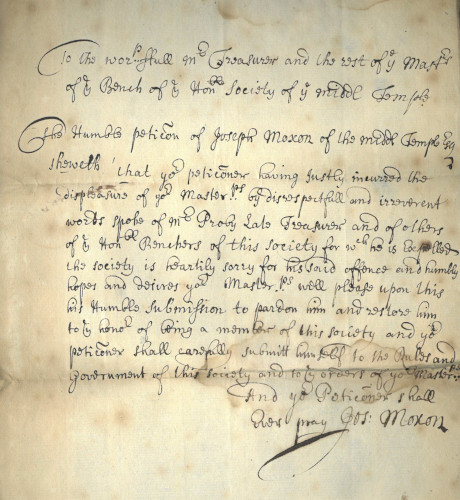

The job of collecting debts was often a thankless task and put the Steward into conflict with the gentlemen of the Inn who were in arrears. On one occasion in 1699, the Steward and his assistant attempted to collect arrears for commons from Joseph Moxon Esq. On being asked to produce the money, Moxon asked whether there had been an order putting his bond into suit. When the Steward produced the order written by the Treasurer, Moxon was reported to say ‘The Treasurer is a rascal, and if he were here I would spit in his face’ and had many unpleasantries to say about the other Masters of the Bench. He also threatened both the officers and said ‘that he would keep them cool and slit their noses’. As a result of his behaviour, Moxon was expelled from the Inn. He petitioned to be allowed to re-join in January 1699/1700 and was allowed back into the Society.

Petition of Joseph Moxon, who was expelled for irreverent words spoken of Mr Proby, Treasurer, that he may be restored as a member of the Inn, c.1699 (MT/21/1/2/VII/18)

Another shocking incident regarding the payment of commons occurred in 1631. Four gentlemen of the Inn were severely reprimanded and punished for continuing commons ‘at the end of Michaelmas Term directly contrary to the Order of the Bench; for assembling under the title of a parliament and entering an order to that effect therein in a book which they called their parliament book, and the keeper thereof the clerk of their parliament; and for fining the Steward 40s. to be cast into commons, awarding him to the Tower for an hour, and then by strong hand putting him into stocks “which they call their Tower” for refusing to provide them commons’. A great many other young gentlemen in commons were involved in this incident, requesting that the Masters of the Bench repeal the order regarding continuing commons at supper ‘with many insolent speeches’. When the Masters refused to repeal the order, ‘calling for pots, [they] threw them at random towards the Bench table and struck divers Masters of the Bench as they were walking, being risen from the board’. Parliament referred to this incident as a ‘notorious outrage, the like thereof had not formerly been known in any other Inn of Court’.

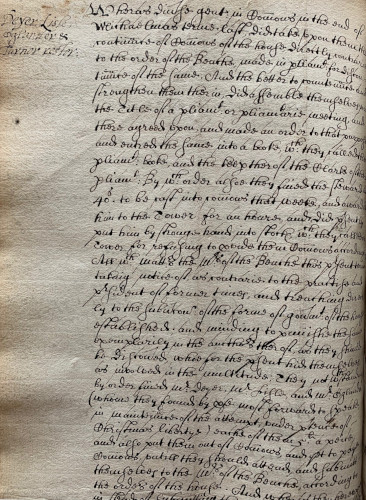

Order of Parliament regarding the outrageous behaviour of Deyer, Lisle, Oglander and Turnor, 11 February 1630/31 (MT/1/MPA/5)

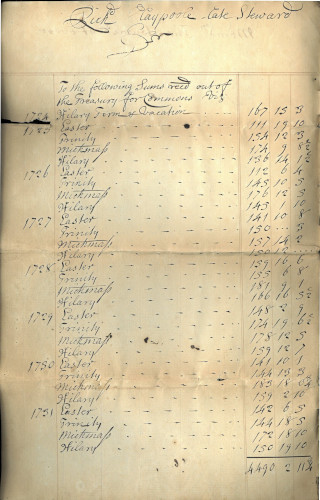

In the first half of the 18th century there were some doubts held about the continued necessity of employing a steward at the Inn. In 1726, a committee was created to consider ‘what proper means shall be used to get in the arrears due to the House; to take into their consideration the necessity of continuing the office of a steward, of his salary, and everything else that belongs or relates to said office’, as well as some other matters. The report of the committee does not survive, but the role of steward continued until 1747, when the new Steward, George Surridge, investigated the accounts of his predecessor and ‘discovered many considerable frauds and abuses’. These findings appear to have been the final nail in the coffin for the position, and it was abolished when the Cook agreed to take on the responsibility of providing commons and collecting money at his own expense, leaving Surridge without employment.

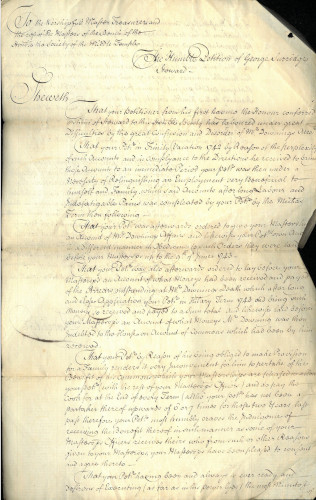

Petition of George Surridge, Steward, concerning the difficulties he encountered with making reason out of the perplexity of Mr Downing’s accounts and requesting an allowance in lieu of commons, c.1744 (MT/21/1/63/X/5)

The position of Steward is just one of many that have fallen into disuse over the seven hundred years of the Inn’s existence. Once key to the day-to-day functioning of the Society and the best-paid servant, his duties were eventually assimilated by another employee to be completed on top of their existing job role. Despite this inglorious end, the role of Steward provides a glimpse into a Middle Temple that functioned very differently to the modern Inn and assists in demonstrating the extent of its evolution over the centuries.