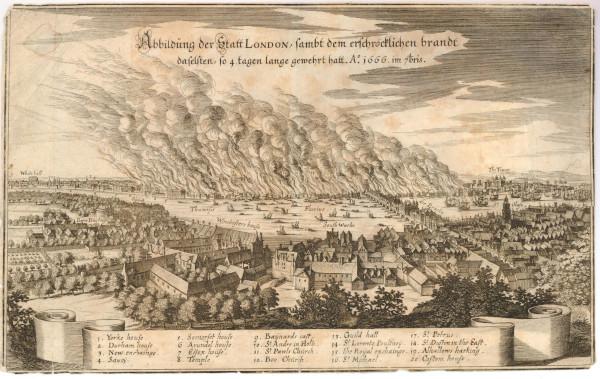

After a long, hot summer in 1666, the medieval City of London was tinder-dry and highly vulnerable to the embers that smouldered in the hundreds of fires lit daily within its walls. Its timber buildings and narrow alleys were a perennial fire hazard that city authorities tried and failed to mitigate. On Sunday 2 September a fire broke out at a bakery in Pudding Lane and quickly spread across the city. The fires would not be put out until Thursday 6 September and for two months after the disaster coal continued to smoulder in cellars. The fire destroyed the old medieval city from near to the Tower of London to the Temple, causing widespread destitution and an unknown number of deaths. A large proportion of the Inner Temple was destroyed, but the Middle Temple escaped the fire with only the loss of Lamb Building.

Print of the Great Fire of London, 1666 © The Trustees of the British Museum

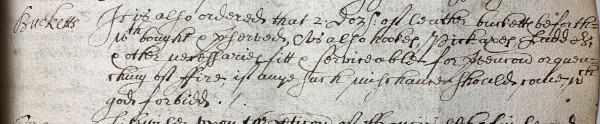

The Inn was aware of the risk of fire and had acquired firefighting equipment by order of Parliament on 27 January 1636/37. The order commanded that ‘Two dozen leather buckets, hooks, pickaxes, ladders, and other necessities for prevention or quenching of fire, shall forthwith be bought and preserved’. In addition to quenching flames with water, one of the main firefighting strategies of the time was to pull down houses in order to create fire breaks and prevent the spread of fire – the logic behind the inclusion of hooks and pickaxes among the equipment. The initial reluctance of the Lord Mayor, Sir Thomas Bloodworth, to allow this strategy to be used within the city greatly contributed to the spread of the Great Fire.

Order of Parliament for the purchase of firefighting equipment, 27 January 1636/37 (MT/1/MPA/5)

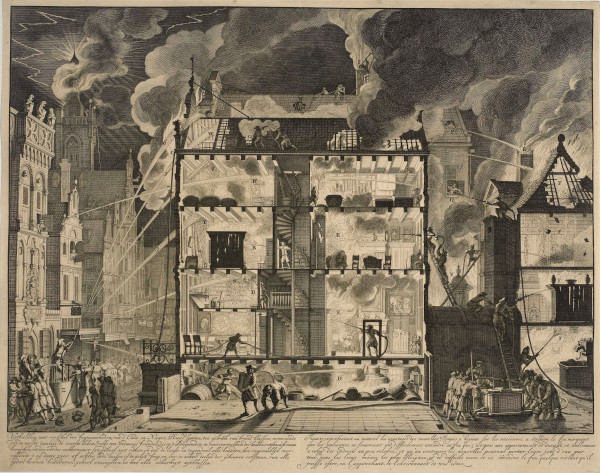

By 1651 the Inn had its own fire engine, or ‘water engine’, which was kept in a shed in Hall Court, later known as Fountain Court. This engine would have been heavy and slow, requiring four men to operate it. The pump would only have been able to squirt six pints of water at a time over very short distances and using it during a fire would have been very dangerous due to the operator’s closeness to the flames. This engine was used during the Great Fire to douse the flames in the Temple – a receipt dated 30 November 1666 shows that a gratuity of £4, or 20 shillings a piece, was granted to four engineers for ‘plying the engine in the Temple at the time of the late dreadful fire’.

A print showing the effectiveness of different fire-engines, the older type in use during the Great Fire on the right and newer, safer engines on the left, c.1690 © The Trustees of the British Museum

The fire reached the Temple on Tuesday 4 September, by which time the King had taken the responsibility for firefighting away from the Lord Mayor and given it to his brother James, Duke of York. Later King James II, the Duke had been made a Bencher of the Inner Temple in 1661. A letter from the courtier Windham Sandys provides an account of the Duke’s actions during the fire and its spread to the Temple. He writes ‘The Duke on Tuesday, about twelve o’clock, was environed with fire; the wind high, blowed such great flakes, and so far… that the Duke was forced to fly for it, and had almost been stifled with the heat… it raged so extreme in Fleet Street on both sides and got between us, and at six of the clock to the King’s Bench Office in the Temple. Night coming on, the flames increased by the wind rising, which appeared to us so terrible to see, from… the shore quite up to the Temple all in flame, and a very great breadth… About eleven of the clock on Tuesday night came several messengers to the Duke for help, and for the engines, and said that there was some hopes of stopping it; that the wind was got to the south, and… had took off the great rage of the fire… By six of the clock on the Wednesday the Duke was there again, and found the fire almost quenched on both sides of the street’.

Plan of the Temple from John Ogilby’s Map of London, 1677. The red line shows the extent of the Great Fire of 1666 and the green line the extent of the Temple fire of 1679.

This was not the end of the Temple’s battle with the fire. By Wednesday evening Sandys recounts that the ‘Temple on fire again. When we came there we found a great fire occasioned by the carelessness of the Templars, who would not open the gates to let the people in to quench it; told the Duke that unless there was a barrister there they durst not open any door. The Duke found no way of saving the [Church] and the Hall by the [Church], but blowing up the Paper house in that court… One of the Templars seeing the gunpowder brought, came to the Duke and told him it was against the rules and charter of the Temple that any should blow that house with gunpowder, upon which Mr Germaine, the Duke’s Master of the Horse, took a cudgel and beat the young lawyer to the purpose… About one o’clock the fire was quenched, and saved the [Church] and hall; so the Duke went home to take some rest not having slept above two or three hours since Sunday night’.

Portrait of James, Duke of York, later King James II

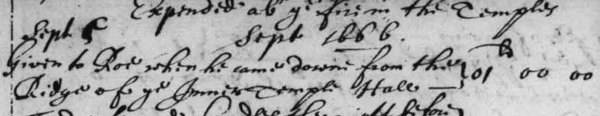

A key figure in preventing the destruction of Inner Temple Hall was Richard Rowe, a mariner who extinguished the flames that had begun to envelop the roof. Rowe was handsomely rewarded by both Inns for his firefighting efforts. The Treasurer’s receipt book records a payment of £1 being ‘Given to Roe when he came down from the ridge of the Inner Temple Hall’, with a later reward of £5 also being paid. He was granted a further £10 as a reward from the Inner Temple and was celebrated in J. Crouch’s poem about the fire, Londinensis Lachrymae.

When after one dayes rest the Temple smokes,

And with fresh fires and fears the Strand provokes,

But with good Conduct all was slak’d that night

By one more valiant than a Templar Knight.

Here a brisk rumour of afrighted gold

Sent hundreds in; more Covetous than bold.

But a brave Seaman up the Tyles did skip

As nimbly as the Cordage of a Ship.

Bestrides the singed Hall on its highest ridge

Moving as if he were on London Bridge,

Or on the Narrow of a Skullers keel:

Feels neither head nor heart nor spirits reel.

Reward given to Richard Rowe after saving Inner Temple Hall from the Great Fire, 6 September 1666 (MT/2/TRB/24)

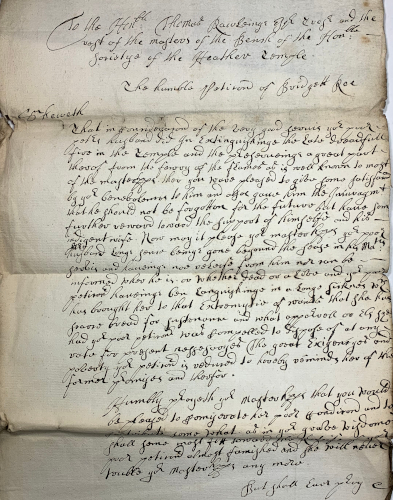

Rowe’s life after the fire was a mystery even to his contemporaries. He disappeared, and his wife, Bridgett, petitioned the Inn for charity. In her petition she wrote ‘… your petitioner’s husband, long since being gone beyond the seas in His Majesty’s service, and having no relief from him nor can be informed where he is or whether dead or alive, and your poor petitioner having been languishing in a long sickness which has brought her now to that extremity of want that she has scarce bread for sustenance and what apparel or else she had your poor petitioner was compelled to dispose of at any rate for present necessities’. The precise date of the surviving petition is unknown, but the Masters of the Bench granted her charity of 40 shillings on 24 January 1667/68 and 20 shillings on 23 June 1675. The disappearance of Rowe, possibly relatively soon after the fire, implies that he may have taken his windfall and made a new life for himself on foreign shores.

Petition of Bridgett Roe for charity from the Middle Temple, c.1668-c.1675 (MT/21/1/II/VII/10)

It is possible to piece together more details about the battle with the Great Fire from the Treasurer’s receipt books. An expense for the mending of pipes and paving by Middle Temple Gate shows that in their desperation, the firefighters ripped up the paving and smashed open the pipes in order to get access to more water. At the time there were no access points to get to the water in the pipes without stopping the flow, so this tactic was used out of desperation. Fire Prevention Regulations, printed by the City of London in 1668, rectified this problem by ordering ‘That plugs be put into the pipes in the most convenient places or every street, whereof all inhabitants may take notice, that breaking of the pipes in disorderly manner maybe avoided.’

Expense for repairing broken water pipes and paving at Middle Temple Gate, 9 September 1666 (MT/2/TRB/24)

At some point during the fire, the Middle Templars feared for the Library. Booksellers, thinking that St Paul’s Cathedral would be spared, had stored their books within the crypts there and were proven mistaken when it burned down and a falling masonry broke into the crypts, destroying everything. There had only been a Library at the Middle Temple for twenty-five years, an earlier one having been lost through theft by the time of King Henry VIII, and the Middle Templars would have been keen to preserve this new and valuable addition to the Society. As a precaution, a porter loaded the library into a boat and the books were taken up the river to Windsor. They remained in storage there until it was safe to return them.

Receipt for expenses incurred moving books to Windsor during the Great Fire of London, 5 November 1666 (MT/2/TRB/24)

Thirty-one men were hired on the 6 September to labour night and day to put out the fire. Large purchases of food and drink, probably to feed these men, were made. Due to the chaos north of the river and the breakdown in the supply chain, Mr Archbold, a barrister and later Bencher and Reader of the Inn, was forced to go over the river to Southwark to buy food. He purchased twenty-two dozen loaves of bread in one trip over the river and purchased the same amount later in the day. Labourers continued to be employed in decreasing numbers until 13 September, when only two men were employed to deal with the aftermath of the fire.

Armorial panel of Nicholas Archbold, Lent Reader 1684

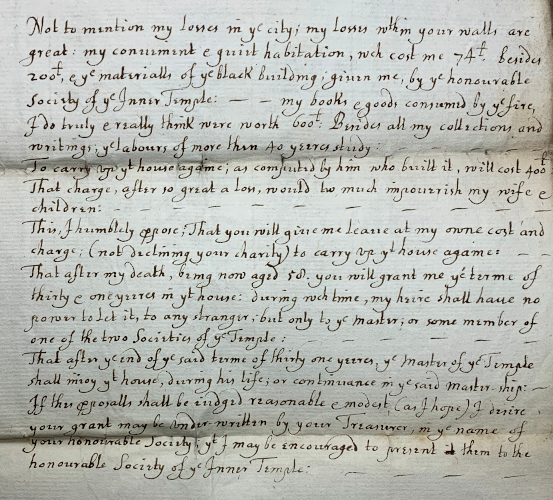

After the fire many people were left in dire financial straits. Richard Ball, the Master of the Temple, suffered the destruction of a great amount of his property. The Master’s House, only built the previous year, was a ruin and he also endured further losses in the City. In November 1666, he petitioned the Masters of the Bench in relation to the loss, stating that he had paid £74 towards the construction of the house and that the Inner Temple had provided £200 in materials. He laments in his petition that his ‘books and goods consumed by the fire, I do really think they were worth £600. Besides all my collections and writings; the labour of more than 40 years study’. The person that originally built the house calculated that it would cost £400 to rebuild and this would impoverish Dr. Ball and his family. He petitioned the Society for leave to rebuild anyway under the condition that his family would be paid rent on the house for thirty-one years after his death, providing them with income. His petition was granted, and the Master’s House was duly rebuilt.

Petition of Richard Ball, Master of the Temple, to rebuild the Master’s House, November 1666 (MT/21/1/94/2/23)

During the Great Fire of London, the Middle Temple had a fortunate escape due to the actions of the firefighters, co-ordinated by the Duke of York, but it would not survive the century intact. In 1679, thirteen years after the Great Fire, a fire broke out in Pump Court that destroyed a large portion of its chambers. Despite these tragedies, Londoners and the Templars rebuilt, taking lessons from the past and reconstructing with better city planning, architecture and safer building materials than before.