For centuries, the rhythms and traditions of the Middle Temple were dictated by the Christian religious calendar. The year was divided into fast days and feast days and one of the most important feast periods was Christmas. Traditional festivities started from as early as All Hallows Day, culminating in twelve days from 25th December to 5th January, and only officially ended at the feast of Candlemas on 2 February. No in-depth account survives of the Middle Temple’s Christmas customs, but inferences can be made by looking at the Inn’s Minutes of Parliament and accounts of festivities at other Inns of Court.

In the 16th century, Christmas at the Inn was often an extremely grand, ceremonial and stately affair. Most of the membership did not join the Society with a view to entering the legal profession and were usually sons of the nobility and gentry. These young gentlemen were provided with a social education, which included learning to ‘practice dancing and all those games proper for nobles, as those brought up in the king’s household are accustomed to practice’ – the Christmas celebrations formed part of this education. Officers for Christmas were appointed from among the membership and these positions were of a mock-courtly form, including a Steward, Marshall, Butler, Master of the Revels, Constable of the Tower and Steward’s Constable. The choices for these positions were formally recorded at the Inn’s November Parliament. According to Inner Temple’s records, the nominees would be informed by letter that they had been chosen and the upcoming Grand Christmas would be announced in Hall. If those chosen as officers for the feast defaulted on their duties, they were fined.

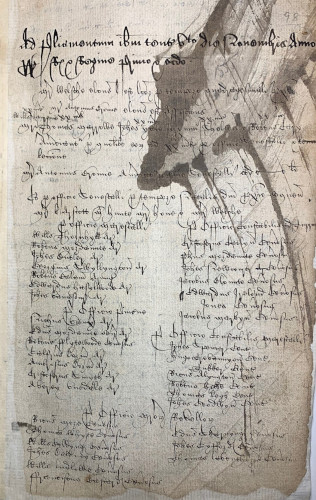

Officers for Christmas listed in the Minutes of Parliament, 4 November 1554 (MT/1/MPA/2)

Although there are no detailed records relating to the Christmas celebrations at Middle Temple, one survives recounting the festivities held at Inner Temple. It is probable that the Christmas celebrations at the two Inns would have been similar with some divergence between the traditions of the two houses. Clear formal rituals are in evidence for the feasts and associated celebrations. According to the records of the Inner Temple, Grand Christmas began on Christmas Eve with a feast and Christmas Day consisted of the attendance at church services and further feasting accompanied by minstrels. On St Stephens Day, now known as Boxing Day, Templars performed strange ceremonies in addition to the customary feast. An extract from the account of Christmas demonstrates their bizarre and ritualised nature.

‘… Then cometh the Master of the Game, apparelled in green velvet, and the Ranger of the Forest also, in a green suit of satin, bearing in his hand a green bow and diverse arrows, with either of them a hunting horn about their necks; blowing together three blasts of venary, they pace round about the fire three times. Then the Master of the Game maketh three curtsies as aforesaid; and desireth to be admitted into his service, etc. All this time the Ranger of the Forest standeth directly behind him. Then the Master of the Games standeth up…’

Print of the interior of Middle Temple Hall prior to the removal of the medieval-style open hearth fireplace, 1800

St Stephen’s Day ended with the introduction of the Lord of Misrule, music and dancing. On the next day, St John’s Day, the Lord of Misrule was abroad causing mischief. After breakfast – on all days consisting of brawn, mustard and malmsey, now known as madeira wine - his power was in suspense ‘until his presence at night; and then his power is most potent’.

Twelfth Night was the culmination of the festivities during the Twelve Days of Christmas. Other Inns of Court and Chancery were invited to see a play and a masque. The Inner Temple’s account of Christmas includes information about these revels and records the only mention of ladies being invited to an event throughout the calendar year, which fits in with the general theme of transgression that was present during the Christmas period. They were allowed to view the play or masque but had to eat dinner separately from the gentlemen – at the Inner Temple the ladies’ banquet would be eaten in the library. Further plays and masques would take place on Candlemas Day with the first recorded performance of William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night taking place in Middle Temple Hall during Candlemas 1602 and the famous lutenist John Dowland performing during Candlemas 1613.

Photograph of the cast of Twelfth Night', performed in Middle Temple Hall in the presence of the Prince of Wales, 1897 (MT/19/PHO/2/1/1)

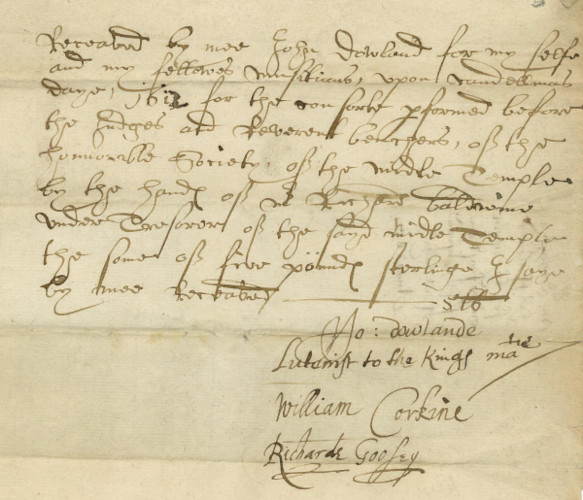

Receipt signed by John Dowland, Lutenist to the King’s Majesty, for a performance at Candlemas 1612/13’ (MT/7/GDE/3)

The grandeur of Christmas celebrations would vary from year to year. A ‘solemn’ Christmas would be a grand, public occasion, and if Christmas was ‘not solemnly kept’, it would be a low-key private affair. Sometimes Christmas would not be celebrated at all – this was the case in 1551 following the default of all those chosen to be officers for Christmas. This year coincided with the last major outbreak of Sweating Sickness in England and it is probable that members were reluctant to return to London. The high mortality rate and sudden death caused by this disease caused panic and an exodus from the city by all who could afford to leave. Christmas was not celebrated grandly the next year either - on the 17 November 1552 it was ordered that ‘On account of scarcity and dearness, Christmas is not to be solemnly kept this year’. This may have been caused by severe crop shortages and the debasement of the currency, which both caused major hardship within the country, reducing the supply of food and inflating its value beyond prices caused by shortages alone. Gentlemen of the Inn were usually required to attend for Christmas, with fines being levied on anyone who did not keep the Christmas vacation, but in this year it was ordered that ‘anyone can leave who pleases’.

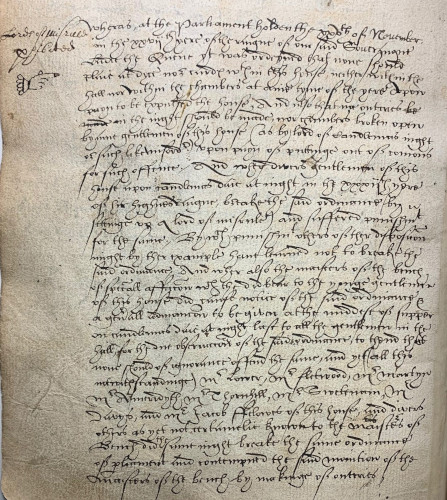

Order that Christmas not be held on account of scarcity and dearness in the Minutes of Parliament, 17 November 1552 (MT/1/MPA/2)

Grand Christmases were held with solemn ceremony, but the festivities could spill into misbehaviour. In 1584, the raucous activities grew too great for the Masters of the Bench to stomach. It was ordered on 25 November that ‘None shall play at dice or cards within this House, neither in the Hall, nor in the chambers, at any time of year, on pain of expulsion. No outcries in the night shall be made, nor chambers broken open, as by the Lord of Candlemas night or such like disorder, on pain of putting out of commons’. While for the most part members of the Inn complied with these regulations, there were occasional outbreaks of disorder. In 1591, a Lord of Misrule was set up on Candlemas night, chambers were broken into and money was demanded from occupants for the Lord of Misrule’s rent. One of the revellers ‘abused Mr. Johnston, a Master of the Bench’ for which he was expelled from the Inn – the others escaped with a 20 s. fine. A similar incident occurred in 1613, but the culprits were not expelled as ‘they pretend that they knew not of the said Statutes’.

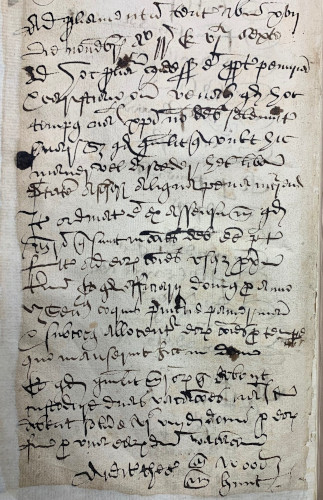

Order regarding the disciplining of Christmas revellers in the Minutes of Parliament, 5 February 1590/91 (MT/1/MPA/2)

Although ‘gaming’ (gambling with dice and cards) at Christmas was banned during the reign of Elizabeth I, it appears that attitudes to the practice relaxed over time. On 28 October 1614, it was ordered that ‘Because disorders at Christmas time may effect the minds and prejudice the estates and fortunes of the young gentlemen, commons of the House shall be kept during Christmas, and none shall play in the several Halls at dice, except gentlemen of the Society and in commons’. This allowance of gaming among Gentleman in commons at the Inn demonstrate that it was lackadaisical in enforcing the 1584 order, and when it took a stricter view on the practise later in the century, gaming had to be explicitly forbidden on an annual basis.

The Gamblers. The Lawyer and the Soldier, c.1668-c.1707 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Overindulgence by the membership continued to be a problem for the Masters of the Bench and on 22 November 1639, the Inn’s Parliament stated that ‘the licentious expressiveness of some gentlemen exceeds all reasonable limits, whereby they bring inconvenience upon themselves, and make many debts upon poor people unpaid, which begets clamour against the Society; and other disorders and abuses in later years have more and more crept in, and have grown to such a height that this misgovernment of these times is become a public scandal, whereof the Judges and State take notice and press hard for reformation’. In response to these pressures, the Benchers Bench forbade the celebration of Christmas that year.

Moralising broadside depicting the Prodigal Son sifted by his parents and found out in his debaucheries – shown emblematically as dice, card-playing, wasting money on fashionable clothes, tennis-playing, smoking, drinking and fathering bastard children, c.1750 © The Trustees of the British Museum

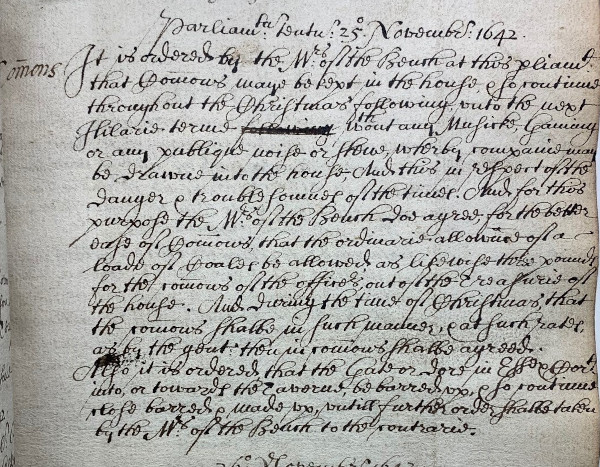

The celebration of Christmasceased altogether during the English Civil War (1642-1651) and rule of the Commonwealth (1649-1660). In 1642, it was ordered that ‘Commons may be kept in the House and so continue throughout Christmas till next Hilary Term, without any music, gaming, public noise, or show, whereby company may be drawn into the House; and this in respect of the danger and troublesomeness of the times’. A temporary measure enacted out of fear soon became permanent. The Puritan government led by Oliver Cromwell, considered traditional Christmas festivities to be sinful and ‘Popish’ and in 1644, an Act of Parliament was passed that banned the festival, with further legislation in June 1647 confirming the festival abolished. Singing, festive foods, shorter workdays and games were all banned over Christmas and no mention of the festival can be found in the Inn’s Minutes of Parliament.

Order forbidding music, gaming, public noise and show at Christmas due to ‘the danger and troublesomeness of the times’ in the Minutes of Parliament, 25 November 1642 (MT/1/MPA/5)

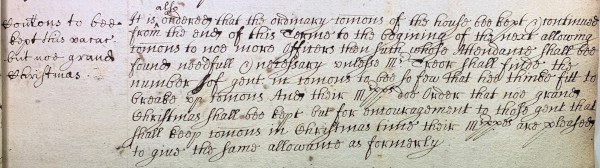

In 1659, some allowances for Christmas were finally made again. It was ordered that ‘no grand Christmas shall be kept, but the same allowance shall be given as formerly for the encouragement of those gentlemen who keep commons in Christmas time’. A modest Christmas was also encouraged the following year, though gaming was expressly forbidden. In 1661, however, long-standing tensions, arising from many years of restrictions on Christmas celebrations, erupted when Lumley Thelwall assumed the title of Lord of Misrule ‘when he went with many strangers and others late at night into Fleet Street and other places, and demanded money of many persons causing the doors of those who refused to be broken open and their money and goods to be taken away’. This was the last recorded incidence of disorder by a Lord of Misrule at the Inn.

Order granting the first allowances for Christmas since 1642 in the Minutes of Parliament, 18 November 1659 (MT/1/MPA/6)

In 1666, the keeping of a public Christmas was again banned by the Inn’s Parliament – no commons were held in Hall and the servants were banned from ‘soliciting the gentlemen for the keeping of a public Christmas’. Twelve gentlemen rebelled against this order over Christmas 1670 and were fined for ‘breaking down the doors of the Hall, Parliament Chamber and kitchen… and setting up a gaming Christmas, persisting after Mr Treasurer’s admonition, and continuing the disorders until a week after Twelfth Day’. These disorders persisted the following year and the offenders went as far as to get a blacksmith to break open the padlock on the doors of Hall. All the gentlemen were expelled and external persons who assisted had information against them exhibited in the Crown Office.

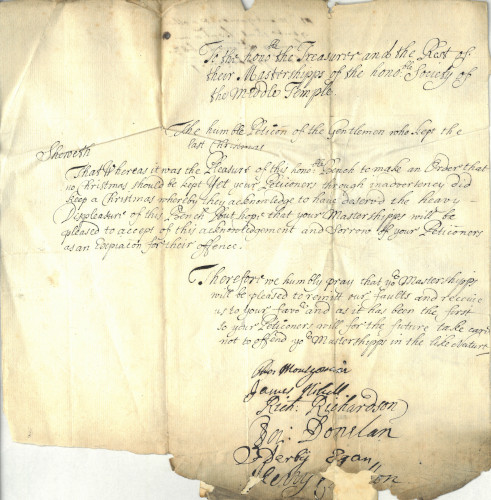

Petition of the gentlemen who kept Christmas 1683 requesting forgiveness for having kept Christmas (MT/21/1/117/III/10)

Orders forbidding gaming Christmases persisted throughout the later part of the 17th century and from 1694, keeping Christmas was forbidden altogether until 1710. The Grand Christmases kept by past generations disappeared and their elaborate rituals were forgotten. The celebration of Christmas would never return to the pomp and ceremony of previous generations.