There are many interesting objects in the historic collections of the Middle Temple and in most cases the origin and history of these items have faded out of living memory. Sometimes the objects themselves can provide clues and when this is combined with research in the Middle Temple Archive, fascinating stories can be brought to light. The history of one set of objects, four 18th century silver salvers, begins with a noticeable discrepancy in the dates of production of the objects and led to a dramatic tale of grand larceny.

Four silver Salvers purchased with the donation of Sir Edmund Saunders, 1709 & 1740

While three of the silver Salvers date to the year 1709, one was assayed in 1740, a fact that can be established due to the practice of silver hallmarking. Hallmarking was introduced in the 1300s, when a law was passed by King Edward I requiring all silver sold in England to be of the same quality and purity as the currency. The London Assay Office, overseen by the Goldsmiths’ Company, authenticated, or assayed, the quality of the silver, issuing it with a mark now known as a hallmark. In 1477, a date letter was introduced to the hallmark, which now allows us to accurately date silver to the year it was assayed. The date marks on four of the salvers in the Middle Temple’s silver collection are inconsistent both with the date of the death of the donor named in the presentation inscription, and with each other. The reason for these discrepancies remained a mystery for many years.

Hallmark of the Three Kings Mazer by Omar Ramsden, 1939

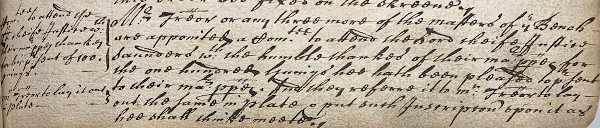

When silver was gifted to the Inn, it was common for a presentation inscription to be engraved on the item to provide information about the identity of the donor for posterity. In the case of the four salvers, Sir Edmund Saunders, Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, is named as the donor. Saunders died in 1683, twenty-five years prior to the assay date of the oldest three salvers. This is an unusually long time between the death of an individual and the date of any posthumous donations to the Society. A search in the Minutes of Parliament around the date of his death revealed that in January 1682/83, Sir Edmund Saunders donated a large sum of £100 to the Inn. He was made a Bencher on 24 November 1682, so may have given a donation in recognition of his election. Saunders would not be a Bencher for long – he was taken ill whilst sitting on the King’s Bench in May 1683 and died on 19 June after giving judgement on the case that he had been overseeing from his deathbed.

Entry in the Minutes of Parliament referring to a gift of £100 from Sir Edmund Saunders, 26 January 1682/83 (MT/1/MPA/6).

An entry in the Treasurers’ Receipt Books dating to January 1682/83 shows that the Masters of the Bench were quick to decide upon how they wished to spend Saunders’ £100 donation. They spent the substantial sum of £177.04.04 on new silver, trading in an old ewer and basin and three old standing salts in order to make up the required amount. With this money, the Inn purchased four large table salts, a large voiding basin, a large gilt bowl, and a ewer and basin. According to the receipt book, all the items purchased at this time were engraved with two coats of arms and an inscription, probably those of the Middle Temple and Sir Edmund Saunders. Only one item from this order survives in the collection – a silver-gilt standing cup with a presentation inscription referring to Saunders’ gift.

Silver-gilt Standing Cup purchased with the donation of Sir Edmund Saunders, 1682

It was common practice throughout the early modern period to trade in old plate and use the money for new silver - table fashions changed and plate got damaged through use. This was the case with the silver purchased with Saunders’ donation. In 1709, only twenty-seven years after their initial purchase, the four salts and the ewer and basin, as well as an additional small salt and ewer and basin, were traded to Sir Richard Hoare and Henry Hoare, famous goldsmiths and founders of C. Hoare & Co, the second oldest extant bank in the United Kingdom. The Society purchased four salvers and had them engraved with Saunders’ coat of arms and a presentation inscription, as they were indirectly purchased with his donated money. Two ladles, and twelve spoons and forks were also bought at this time.

Receipt for an order of silverware from Sir Richard Hoare and Henry Hoare, goldsmiths, 1709 (MT/2/TRB/67)

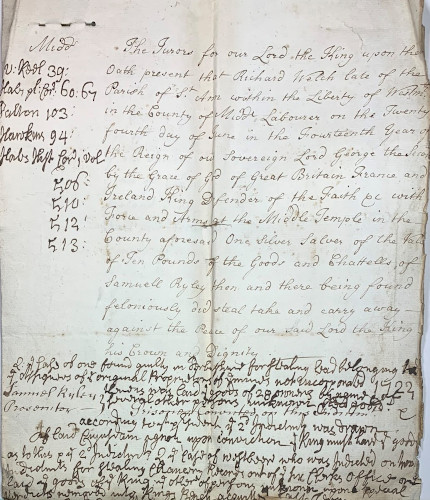

A document recently found in the loose papers collection in the archive has revealed the reason why only three of the salvers have the 1709 date mark. In 1740, a labourer called Richard Welch was convicted of stealing a silver salver from the Inn. Consultation of the records of the Old Bailey reveals details of Welch’s trial, held on 3 September 1740, in which Samuel Riley, Chief Butler of the Society, testified. As Chief Butler, Riley was responsible for the care and security of the silver. He spoke to the courtroom about the day he missed the salver, stating ‘On the 24th of June last, which was in Trinity Term, it was our Grand Day; and this is the plate that I lost that day out of the Middle Temple Hall, about 5 o’clock in the afternoon. This salver is the fellow to what we then lost – we have four of them in all. There’s the Temple Arms upon it and I can swear ‘tis what I lost. I missed it about 5 o’clock and had it in my hand about half an hour before’.

New Sessions House, Old Bailey, 1748 © The Trustees of the British Museum

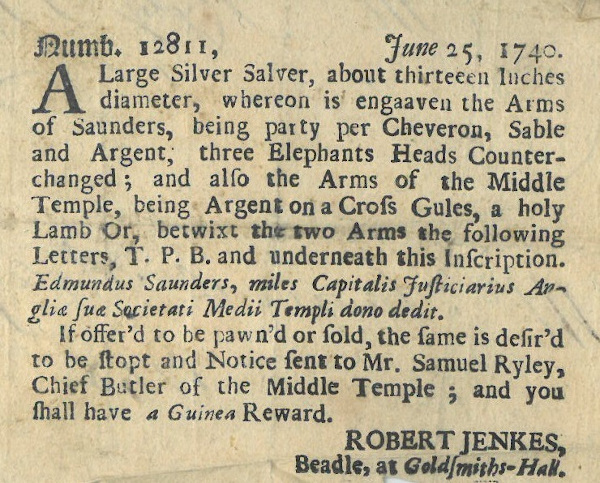

Alarm was raised immediately over the theft of the plate. The loss was reported to Goldsmiths’ Hall and on the 25 June, the day after the theft, Robert Jenkes, Beadle of Goldsmiths’, issued a notice with a description of the lost salver and an offered reward of four guineas for its return. The Goldsmiths’ Company employed ‘Warning Carriers’ to alert the trade to recent thefts and a company wallbook dating to 1744 records the names of three officers who were to visit one hundred and sixty-two goldsmiths, as well as pawnbrokers, jewellers, toymen and watchmakers to raise the alarm. By law, all London retailers were required to enquire as to the source of any plate offered for sale and to record its information.

Notice of theft and offer of reward for the return of a silver Salver belonging to the Middle Temple, 25 June 1740

The vigilance of those in the silver trade proved the undoing of Welch. He took two of the feet of the salver to Mr Urton, pawnbroker, who had known him for eight years and described him as ‘always very poor’. Welch had bought some pieces to Urton on Thursday 3 July and claimed to have bought them from a working silversmith. On Saturday 5 July, Welch brought a further two pieces to Mr Urton, who became suspicious of his sudden windfall. He stopped the sale and advertised the feet in the papers.

Mr Riley recalls in his testimony ‘Some time after it was lost, I heard by an advertisement that Mr Urton, a pawnbroker, had stopped a piece of plate; I went to him and found two pieces in his custody (which belonged to the feet of the Salver) the whole bottom I found in the prisoner’s lodgings, up two pair of stairs, in Windmill Street, where he was taken… We found the door locked, and upon entering the room and searching it, we discovered the plate upon a shelf over the door; it had been burnt in the fire and bent back, almost quite double. The pieces which we found at Mr Urton’s belong to it’.

Record of the conviction of Richard Welch, labourer, for the theft of a silver Salver (MT/21/1/51/IX/1)

Welch was found guilty and was convicted of grand larceny. He was sentenced to transportation and was sent to America in September 1740, arriving in Maryland probably around six weeks later. The province of Maryland received a large share of transported convicts and African slaves at the time due to their high demand for cheap labour, and on arrival it was common for convicts to be auctioned off to the highest bidder. The primary export of the province was tobacco and Welch was probably put to work as an indentured servant on a tobacco plantation, though his ultimate fate is uncertain. While many convicts stayed in America, a known problem with the practice of transportation was that some managed to escape their servitude and return to Britain. If they were caught, they were sentenced to capital punishment and many preferred the death sentence to undergoing transportation and indentured servitude for a second time.

Convicts being put to work in agriculture, 1745-1807 © The Trustees of the British Museum

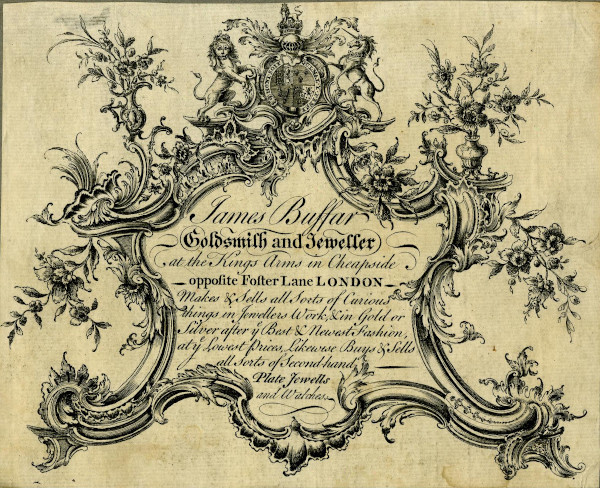

The extreme damage that the salver suffered during the theft meant that it was impossible to salvage. The Inn brought it to James Buffar, a goldsmith at the King’s Arms, opposite Foster Lane, and partially traded it in for a replacement – the salver with the 1740 date mark in the Middle Temple’s collection. The theft of the salver cost the Society the substantial sum of £5.17.03, though the retrieval of the stolen property saved the Inn £11 for the cost of precious metal.

Receipt for new silver Salver from James Buffar, 1740 (MT/2/TRB/99)

Trade Card for James Buffar, silversmith, c.1748 © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Middle Temple Archive is the most complete of the four Inns of Court and there are many loose documents that record the minutiae of the everyday administration of the Society going back to the 17th century. The story of the four silver salvers is one that could easily have been lost if not for a decision made centuries ago to keep one piece of paper.