After the order of Knights Templar was dissolved, the Temple lands were officially transferred by the Pope to the Knights Hospitaller, another religious military order, although for the coming decades the Crown tended to treat the Temple as its own land, installing favourites such as Hugh Despenser the Younger. The Hospitallers did not actually take possession until 1338, but at this point, having been established at Clerkenwell for well over a century, had no use for the land themselves and began to let the property out.

It is generally thought that the Societies of the Inner and Middle Temple came into being in the mid-14th century, following the return of King Edward III’s courts from York to Westminster. This would have led to significant numbers of lawyers seeking permanent accommodation within easy reach of the courts at Westminster, coinciding neatly with the opportunity to rent such accommodation from the Knights Hospitaller on the Temple land.

No records survive of the foundation of either society, and much discussion has been devoted to whether or not the two were formed from the fission of one Temple society. It is now thought that they were separate from the start, there having been two separate halls in the Temple since the days of the Templars, the ‘Middle’ hall originally being to the east of what would become Middle Temple Lane.

The earliest known documentary reference to the Middle Temple occurs in records dating from the reign of Richard II in 1388, recording the appointment of one ‘Willelmus Hankforde medii templi’ as a Serjeant-at-Law. Around the same time, Geoffrey Chaucer referred to a ‘Maunciple… of a temple’ in the prologue to the Canterbury Tales. In 1381, the Temple was sacked in the course of Wat Tyler’s Peasants’ Revolt. Books and paperwork were burned, buildings damaged and the records of the ‘apprentices’ were torn up and destroyed.

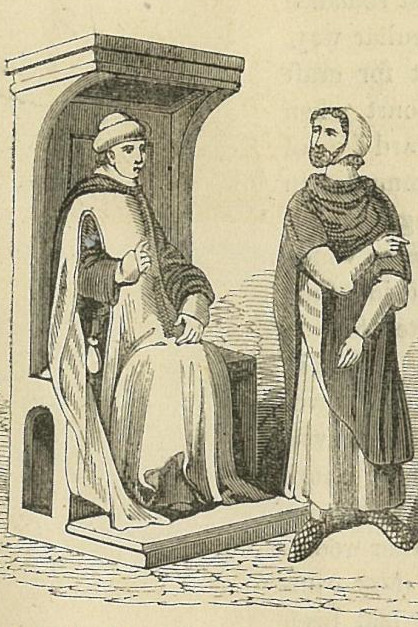

By the early 1400s, the Inn functioned as a place of learning and education. Students were admitted into the society and served their superiors in Hall until they completed the first stage of their education. The students were taught through several different methods, but the centrepiece of the curriculum was the twice-yearly practice of Reading. Unlike the one-night-only events familiar to the modern Inn, these would take place over the course of several weeks in the Lent and Autumn ‘vacations’. The Reader, a member of standing within the Inn, would expound upon a particular statute, and disputation and discussion of sample cases would follow. The Reading would be accompanied by grand feasting, much of it at the Readers’ own expense.

By the early 1400s, the Inn functioned as a place of learning and education. Students were admitted into the society and served their superiors in Hall until they completed the first stage of their education. The students were taught through several different methods, but the centrepiece of the curriculum was the twice-yearly practice of Reading. Unlike the one-night-only events familiar to the modern Inn, these would take place over the course of several weeks in the Lent and Autumn ‘vacations’. The Reader, a member of standing within the Inn, would expound upon a particular statute, and disputation and discussion of sample cases would follow. The Reading would be accompanied by grand feasting, much of it at the Readers’ own expense.

Mock courts were set up for ‘Mooting’, in which legal cases and problems would be pled and argued. This practice gave rise to the phrase and practice of ‘Call to the Bar’. Junior students would sit within the ‘Bar’ or bench of the court, listening to the case, while those among their number who had undertaken sufficient study would stand outermost, at the bench, to plead the cases, and thus came to be called ‘Utter Barristers’. It is not quite clear when this status came to qualify those awarded it to plead in court, but it had become commonplace by the later 1500s, and was formalised towards the end of the century.

While the loss of all internal records from this period casts these early centuries into darkness and conjecture, it is nonetheless clear that by the end of the fourteenth century the Middle Temple had formed into a well-established society with its own distinct traditions and practices, and which also commanded a place of importance and prestige within the social order of the time.