The Middle Temple Parliament is the Society’s ruling body and has been responsible for its government from before the existence of its earliest surviving records until the present day. Parliament has been the executive power of the Inn for centuries, but its authority has not always gone unchallenged. From the late 17th to 18th centuries another parliamentary body rose to challenge it; the ‘Vacation Parliament’ formed of barristers and students of the Society and held during vacation times in contrast to the Inn’s formal term time Parliaments. These Vacation Parliaments met to give voice to grievances of the barristers and students, but on several occasions they also proposed limiting the authority of the Bench and creating a system that appeared to be modelled on the Parliament at Westminster, with a lower house reining in the powers of an upper house and supplanting it in many areas of governance.

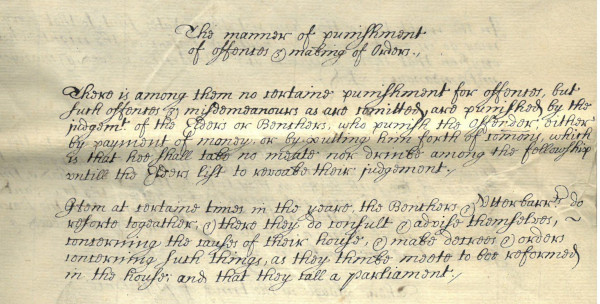

Extract from a 17th century manuscript copy of the state, orders and customs of the Middle Temple, taken from a report to Henry VIII in the Cotton Manuscripts (MT/21/2/6/FW)

In a 1731 report by Benchers into the nature and origin of the Vacation Parliaments, it is recorded that its members cited precedent to justify their right to meet, but there was no precedent in the Inn’s records for the division of its government between two houses or estates. In the earliest centuries of the Society’s existence, three or four governors were elected to act as an executive governing body for the next twelve months, the earliest known form of the Inn’s Parliament. However, the earliest surviving minutes of Parliament, dating from 1501-1525, show that during this period its decisions were made by the ‘company’ or ‘fellowship’ rather than by the Masters of the Bench alone. It is recorded in the 1731 report that the Vacation Parliaments cited page 196 of William Dugdale’s book, Origines Juridiciales (1666) as justification for their right to meet – this quoted a report produced during the time of Henry VIII, where there is a gap in the official records of the Inn, that stated ‘at certain times of the year the Benchers and Utter-Barristers do resort together, and there they do consult and advise themselves, concerning the causes of their House, and make Decrees and Orders concerning such things, as they think moot to be reformed in the House and that they call a Parliament’. It is likely that the barristers were involved in the government of the Inn at this time through its main Parliament rather than forming their own separate body, but by the second half of the 16th century power of governance over the Inn became solely invested in the Benchers.

Evidence provided by the Vacation Parliaments justifying their right to meet. Extract of a report by the Bench regarding the Vacation Parliaments, 1731 (MT/21/1/56/3/13)

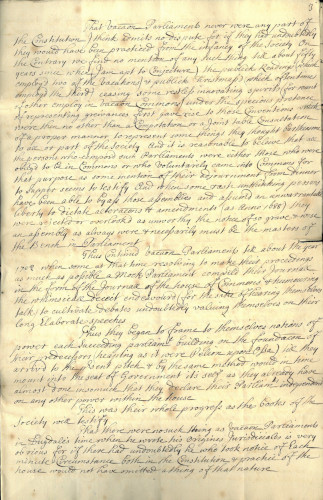

The first mention in the official records regarding anything approaching a second parliament was on 7 February 1589 when the Minutes of Parliament state that ‘The order set down in the buttery book by the Christmas lord and Utter barristers then in commons for Henry Poole, the Steward, from his office for ill provision of victual and other abuses is revoked, as the makers of the order had no sufficient authority, but his misdemeanours and evil usage of the Butlers and other officers is referred to the Treasurer and two others of the Bench’. It was common at the time for a Lord of Misrule to reverse the social order as part of Christmas festivities, and it appears as though this incident was part of the revelry with no real authority behind it. However, the subsequent referral of the complaints of the barristers to the Treasurer and Masters of the Bench implies that there was some merit to their complaints, and demonstrates that the leadership of the Inn was open to listening and acting on the remonstrances of the membership during this period.

Minutes of Parliament regarding the making of an order by the Christmas Lord and Utter barristers, 7 February 1589 (MT/1/MPA/3)

The autobiography of Roger North (1653-1734), made a Bencher of the Middle Temple in 1682, provides more context to the Vacation Parliaments. He explicitly associates them with Christmas festivities and implies that they might have met informally for some time longer than they appear in the official records. He writes ‘the barristers and those under the bar, pretend to a subordinate authority, and that allowing the benchers to govern in terms, they have the sway in the vacation, and on occasion of grievances, they make a parliament of themselves, even in term time… they pretend to undo and oppose the invasions of their rights advanced by the benchers, when they stretch their authority too far. And young fellows get together in this manner, being pert and witty, will, by aping the national parliament… make excellent sport… and the wiser sort make jest of it… but the ill bred, sour part of the bench will be as ridiculously in earnest, and like state politicians argue for their own government…’. North acknowledges that occasionally the young gentlemen got out of hand and the Benchers had to use their powers as members of the judiciary to quell the rebellion.

Armorial panel of Roger North, Lent Reader 1682 and Treasurer 1683

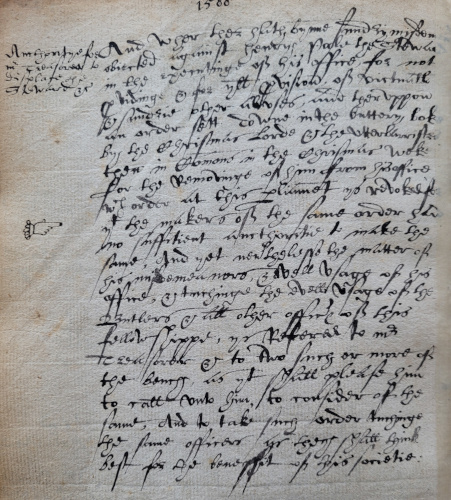

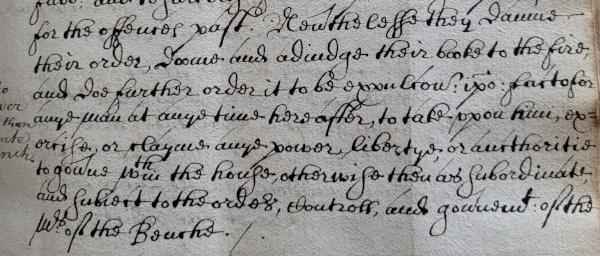

One of these occasions was outrageous enough to make its way into the minutes of Parliament of 11 February 1631. Messrs. Deyer, Lisle and Oglander were fined £5 each and were put out of commons ‘yet to pay commons until they submit’. One part of the behaviour that invoked this penalty was ‘for assembling under the title of a parliament and entering an order of that effect therin in a book which they called their parliament book and the keeper therof the clerk of their parliament’. After further outrages, including the assault of Masters of the Bench in Hall, Deyer and Oglander were committed to the King’s Bench Prison with Lisle and another gentleman named Turnor being bound to good behaviour. All four were eventually received back into commons but only if ‘They damn their order and doom their book to the fire’ and it was ordered that it ‘hereafter to be ipso facto expulsion for any one to claim any power to govern within the House otherwise than as subordinate to the orders of the Masters of the Bench’.

Minutes of Parliament regarding the outrages committed by barristers against Masters of the Bench, 11 February 1631 (MT/1/MPA/5)

The Benchers of 1731, while grappling with the declared rights of the Vacation Parliament of the day, could ‘find no mention of [them] till about fifty years since’ in the official records. A corroborating document lists the orders of the Vacation Parliaments as having been entered into the Buttery Books from 1681 – these books were kept in the buttery next to the Hall and were where the Head Butler recorded the names of gentlemen in commons each day - and notes that there were no Vacation Parliaments recorded from 1632-1641. The Buttery Books presently only survive from 1745, so we are reliant on this document for knowledge of the content of these lost records. Information found in North’s biography suggests that the 1680s may have been when barristers met to address grievances more seriously – at the time many of them felt aggrieved about the rebuilding of the Inn after the fire of 1679 and ‘the gentlemen were more united than had been known, even the gravest of the barristers engaged with them, which was rare, and spoke their cause just… this rebellion had mortified the benchers so as they were to submit to reason’.

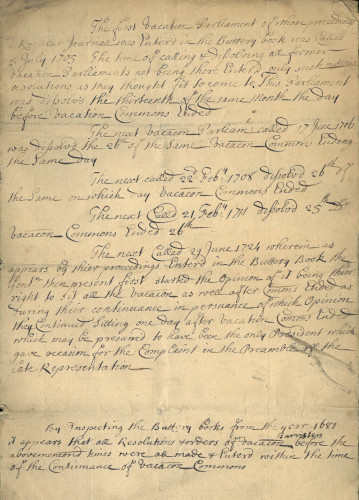

Document noting the dates of Vacation Parliaments in the Buttery Books of the Inn, c.1730 (MT/21/1/56/3/11)

North talks about the form of the extraordinary Parliament and states that the first thing they did was meet at the ‘Apollo’ and choose a speaker, ‘but this assembly was so tumultuous’ that they then ‘proceeded to nominate some one person out of every staircase as an intendant for the rest, to take care of the particular interest of that staircase’, essentially creating MPs for Middle Temple staircase constituencies. North commented that ‘the most reasonable kept out of these troublesome meetings, and those chiefly attended who expected to profit by hard dealing and crossgrainedness’, but he viewed them as important in protecting the interests of the membership against impositions by the Benchers. The differences regarding the rebuilding of the Inn were later resolved with North stating that the agreed model for rebuilding chambers ‘was delivered into the Treasury as the act of the whole Society, and was the happiest resolution of a perplexed touchy affair that I have known’.

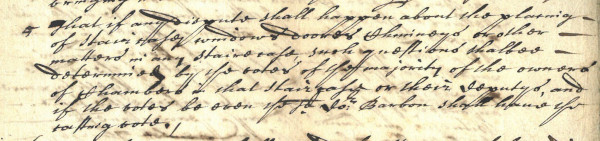

Orders of the committee for rebuilding the Middle Temple after the fire, including references to the resolution of disputes by a majority vote of owners of chambers in a particular staircase, 15 March 1679 (MT/6/RBW/14)

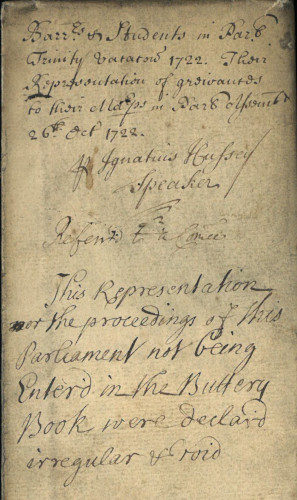

According to the list of orders and proceedings entered into the Buttery Books, in 1705 the practice began of officially recording the minutes of the Vacation in Parliaments in the back of these books. The writer of the 1731 report, less certain in their dates, states that in about 1702 ‘resolving to make their proceedings as much as possible a mock parliament compiled their journal in the form of the journal of the House of Commons’. The Bench appeared to give their tacit approval to this practice as a remonstrance made by the 1722 Vacation Parliament ‘not being entered into the Buttery book were declared irregular and void’. They also engaged with the representations of the barristers, acknowledging the validity of complaints and making changes to the Inn’s policies when they saw that improvement should be made.

Extract declaring the proceedings of the Vacation Parliament and barrister’s remonstrance void, 1722 (MT/21/1/56/3/9)

The requirement of the Benchers for the Vacation Parliament proceedings to be officially entered into the Buttery Book, and their willingness to engage with the barristers’ complaints, soon began to backfire on them as it created precedent and lent legitimacy to the proceedings. This is addressed in the 1731 report, which states ‘… they began to frame themselves notions of power each succeeding parliament building on the foundation of their predecessors... [and] would in time mount into the seat of government itself as they already have almost done insomuch that they declare their Parliament independent on any other power within the house’. The author of the report was highly sceptical of the authority of these parliaments and describes their members as ‘young barristers and students, the major part of the barristers not having gone through their vacation commons and of the students perhaps scarce one in five has attained the age of twenty years’. These appear to be the ‘pert and witty’ young men previously described by North, but as the century progressed their pretend subordinate authority widened in its scope, and appears to have become more earnest in the challenge it posed to the authority of the Benchers.

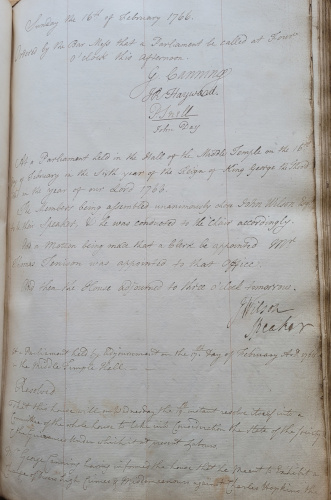

Minutes of the Vacation Parliament held on Sunday 16 February 1766 (MT/7/BUB/2)

By the 1760s the members of the Vacation Parliaments viewed themselves as having legitimate power in the governance of the Inn. In the representation of the February 1766 Vacation Parliament, they declare that having searched into their earliest records and ‘though its origin is involved in the obscurity of remote antiquity, yet it appears from the earliest vestiges of parliaments which we can discover, that the two estates were coeval with the institution of the Society, each possessed of is proper constitutional powers’. These findings were at odds with the information in the early records of the Society. The powers that they claimed for themselves were deliberating on and framing laws for the interior governance of the Society, enquiring into abuses committed by its officers and servants and bringing them to justice, punishing all contempt for its authority and privileges, applying to the ‘Upper House’ for redress of grievances, of issuing edicts that have the force of law between sitting parliaments, directing the application of the Society’s funds and making decisions on taxes, disposing of ‘all places of trust and honour’, and determining the qualifications of gentlemen entering into the law. They called this address to the Benchers their ‘Declaration of Rights’.

Representation of the Middle Temple Vacation Parliament held in February 1766 (MT/21/1/33/6/2)

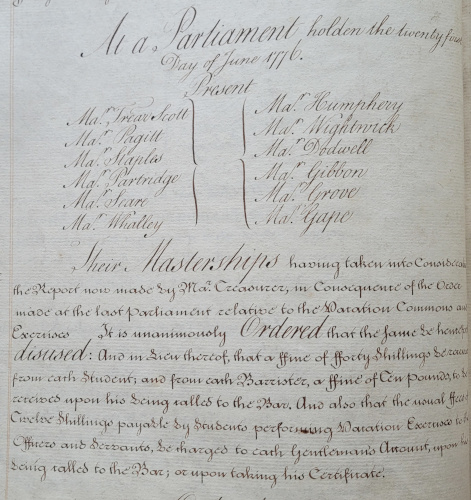

The final entry of a Vacation Parliament into the Buttery Books is dated 5 July 1774, one year before the American Revolution began. Given that many future American Revolutionaries had been students at the Inn, including John Rutledge, Edward Rutledge, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Thomas Pinckney, it might be conjectured that there were fears that the culture of rebellion, so prevalent at the Inn, may have had some influence on these figures. As the anonymous author of the 1731 report writes, these Parliaments were seen as ‘mutinous assemblies tending not only to the disturbance of the peace (but probably to the subversion of the government) of this house infusing into the minds of unwary youth principles of sedition and inuring them to notions of disrespect and disobedience which in all Societies of men directly tend towards anarchy and confusion’. This may have been one of the motivations behind the order of the Inn’s Parliament dated 21 June 1776, which commanded that vacation commons and exercises be abolished - this effectively also abolishing the Vacation Parliaments and ended the overt challenges to the governance of the Benchers by young barristers and students.

Order of Parliament that vacation commons and exercises be disused, 21 June 1776 (MT/1/MPA/9)

The years 1681 to 1774 were the heyday of Middle Temple’s Vacation Parliaments and this coincided with a wider culture heavily influenced by Whig liberalism and the philosophy of John Locke, which argued that governments required the consent of the governed and that men had three natural rights – life, liberty, and property. It is no coincidence that the period during which they convened overlapped with the Glorious Revolution in 1688 and the American Revolution, which began in 1775, and it is probable that the Middle Temple served as a proving ground for these liberal ideas. The Vacation Parliaments allowed young gentlemen to test themselves during their education against the Inn’s Parliament before entering the higher stake spheres of law and government, where they would eventually use these ideas to assist in laying the foundations of the modern state.