The Middle Temple Library has experienced many changes over the centuries. The Inn’s medieval Library was dissolved after all its books were stolen, leaving a gap of over one hundred years before the foundation of the modern library. This had its origins in the bequest of bibliophile Robert Ashley, who died in 1641 and left the extensive collection of books in his chambers to the Inn. The accommodations of the library, with the increasing requirements of an ever-expanding collection of books, altered substantially from its initially humble beginnings, with arguably the most architecturally impressive housing for it being a large Victorian gothic revival structure that opened in 1861.

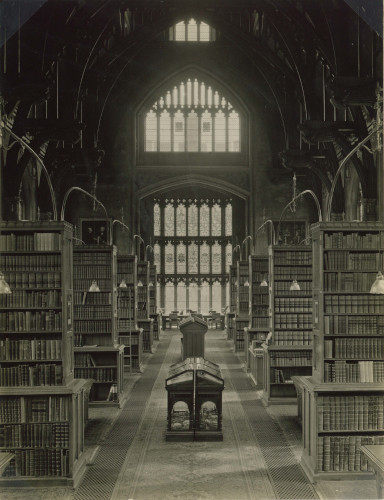

Photograph of the Victorian Middle Temple Library, c.1935 (MT/19/PHO/5/8)

At the beginning of the 1850s, the library was housed in the present-day Parliament Chamber, which was constructed in 1824. However, despite the space being adequate in size for the number of members consulting the volumes, the demand for space for the books quickly outpaced the capacity of this library. Consultations began about the possibility of building a new library in 1852 but stalled for many years due to issues finding an appropriate site. An interim solution was suggested in 1854 by the Master of the Library that involved widening the upper gallery that was in the room at that time. The Inn’s Parliament decided to go ahead with the alterations, which was estimated to cost £200-£300, over the expense of building a new Library for the sum of £10,000-£15,000, and to use the additional money accrued in interest in the meantime to help fund a future build.

Report on the potential expansion of Library accommodation by the Master of the Library, 13 January 1854 (MT/1/PPA/2606a)

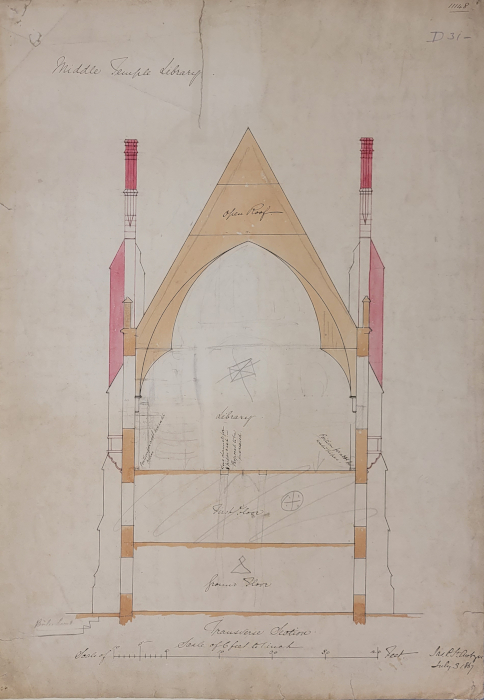

In 1857, it was finally decided to proceed with building the new Library. The architect Henry Robert Abraham (1803-1877) was commissioned to create the design in the popular gothic revival style of the period and George Myers (1803-1875), best known for his work with the noted architect Augustus Pugin, was employed to oversee the construction. The design of the library, in common with others in the same architectural style, drew inspiration from medieval churches and castles. It consisted of three floors, with the upper floor having capacity for 50,000 to 60,000 books, and space for chambers on the bottom-most floor. The roof was of medieval open hammerbeam design, incorporating a similar element to the distinctive double hammerbeam roof of Middle Temple Hall, and at one end there was a great oriel window decorated with heraldic stained glass.

Photograph of the interior of the Middle Temple Library looking north, c.1927 (MT/19/PHO/5/2/2)

The proposed construction of the new library immediately caused controversy, with concerns being raised over the first proposed site in 1857, this being Fountain Court. The main objection to this location was that this would have meant the destruction of the much beloved Middle Temple Fountain, ‘… the only fountain in London that really did its work, and was a pleasant fountain withal, rich with many dramatic associations’. After a petition against this plan was submitted by the Inn’s barristers, it was advised by Mr Abraham to sacrifice the Garden Court chambers for the project as the library building would have chambers built under it if it were constructed on that site. The pulling down of Plowden Buildings and other sites at Brick Court and Elm Court were also suggested by Benchers as possible solutions. In the end, a site at the south-west of the garden was decided upon. The foundation stone for the new edifice was ceremonially laid on 16 August 1858, and it was officially opened three years later on 31 October 1861 by H.R.H. Albert, Prince of Wales.

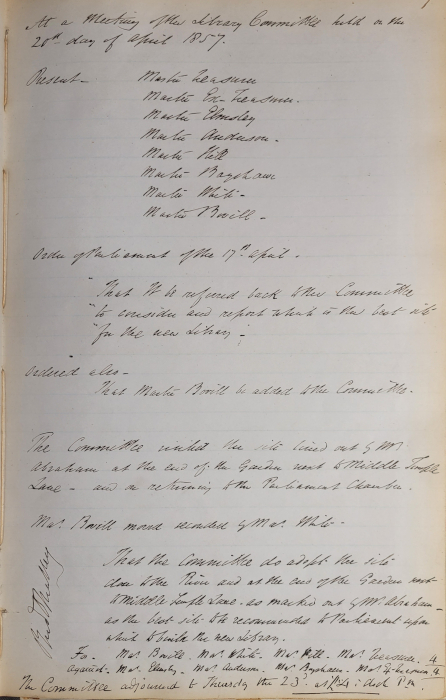

Library Committee minutes discussing plans for the new Library’s location, 14 April 1857 (MT/9/LCM/1)

The new library building, although fashionable, was not received with universal acclaim. One ‘Templar’, writing anonymously to the editor of The Morning Post on 22 November 1869 with an extensive list of complaints about the Inn, objected that ‘The hideous structure known as the Middle Temple Library will, unless it be as unstable as it is unsightly, furnish for many years to come a monument of the extremely bad taste with which the governing body of the Inn frittered away a large portion of its funds… [it] testifies how something like £40,000 was got rid of’.

Plan showing a transverse section of the Middle Temple Library, 3 July 1867

In addition to the aesthetic and financial criticisms, there were more pressing concerns that had a great impact on the comfort of the library’s users – the biggest of which was that the large, cavernous, church-like space was extremely difficult to keep warm. One user complained ‘The draught of air is terrible, especially when the wind blows from the north-west; indeed, so bad is it that I am surprised that more men have not caught cold, as I and several others have done. Indeed, one of our library porters died suddenly on Saturday from bronchitis, which, if not caught, was certainly developed by being in that cold draughty place’.

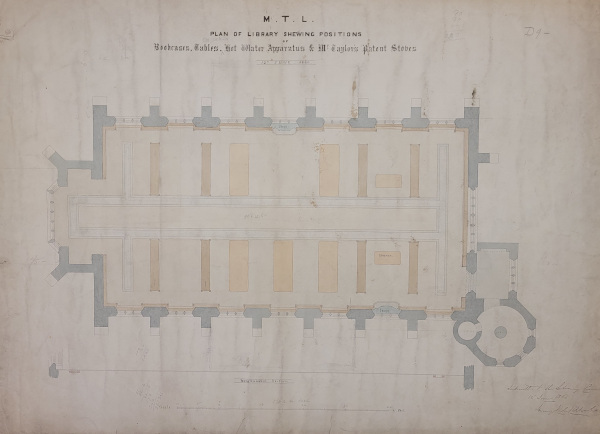

Plan of the Library including the position of bookcases, tables, hot water apparatus and stoves, 12 June 1860

Despite the complaints about the cold, the library had been fitted with two stoves in its main room and anteroom and was additionally supplied with an innovative new method of heating – the radiator. This recent invention was developed and brought to market in the 1840s-1850s, but the modern upright radiator design was not invented until 1863 and could not be considered for installation in the library. Instead, trenches containing pipes were dug under the library floors, over which an iron trellis was laid to increase the surface area of the radiating heat. The pipes were connected to a furnace in the library tower basement, which fed hot steam into them. While innovative, it is possible that the novelty of the heating method led to a miscalculation about the ability of the system to adequately heat a large, relatively uninsulated space. This issue appears to have been extremely difficult to remedy as complaints about draughts continued for many decades and in 1905, over 40 years after the library was opened, alterations were undertaken to try and fix the perennial issue.

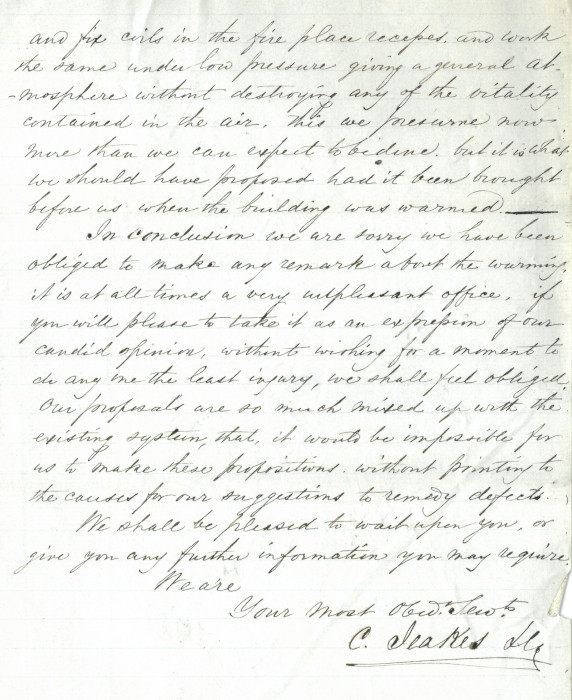

A critique of the library’s heating system by C. Jeakes Ltd. included with proposals for its improvement, 24 October 1870 (MT/9/LIB/68)

Another cause of discomfort was the lighting in the library. Although there was an abundance of natural light, after the sun set he reading space was illuminated by oil lamps. It was believed by some that the Middle Temple was over-economising on the lamps and one complaint from 1877 states that ‘… a few lamps are lighted about four o’clock – one or two to each table … [but] any one coming in about half-past five in the evening… will be lucky to find as many as four lamps alight in the whole library’. These attempts at economy were unsurprising given the complaints of the Finance Committee, which noted on 14 November 1871 that ‘the annual cost of lighting the oil lamps in the Parliament Chamber and Lecture Room during Term amounts to £30 and upwards per annum’ and ordered that it be ‘requested to enquire and report if a more economical arrangement cannot be made’.

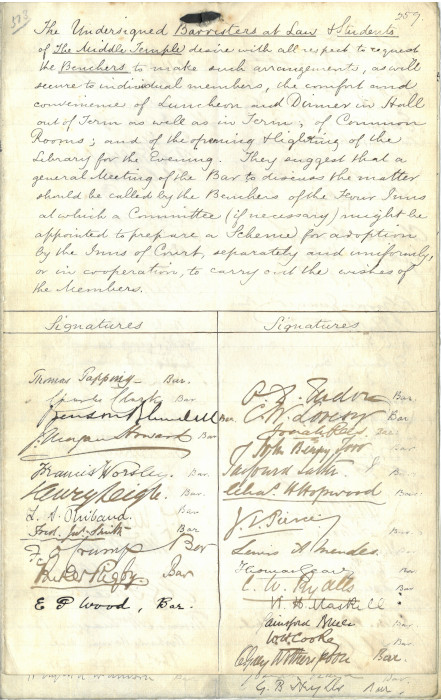

Petition from barristers and students for luncheon and dinner to be held in Hall outside of term, and for the opening and lighting of the library during the evening, 1871 (MT/1/PPA/3731a)

Complaints about oil lighting were made redundant when electric lighting was eventually installed. Inner Temple pioneered its introduction in the Temple in 1885, but the Middle Temple had been unable to follow suit at this time due to lack of space to house a generator. After the first London suppliers started providing electricity in 1891, it finally became possible for the Inn to install this new method of lighting. This was implemented across the Hall, Bench Apartments, Library and Treasury Offices in 1894, with two possible lighting configurations being suggested for the library – overhead pendants over every table, or a softer lighting consisting of shaded lamps on tables and bracket lights being fixed to shelves. The Benchers chose the softer lighting method. However, this new kind of lighting was not without its own problems. There were times when the lights would go dim and they would occasionally fail entirely, plunging the library into darkness. Possibly in response to these issues, the system for electric lighting was renovated in 1900.

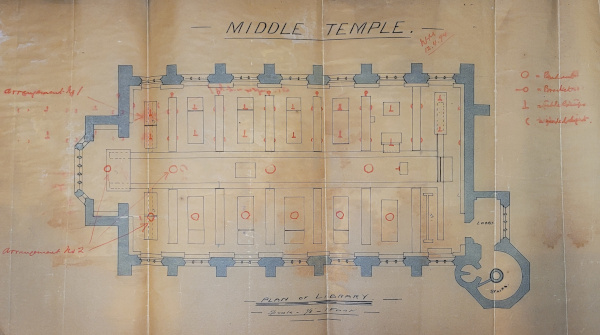

Plan of Middle Temple Library showing two different proposals of lighting the building with electricity, c.1894 (MT/6/RBW/206)

Another critique of the 1860s library was that it did not allow for much expansion room and by the 1920s the building was once again proving inadequate to the needs of the Society. Several solutions for expansion were proposed, including the creation of underground storerooms for books, moving the Common Room, which was at that time housed in the library building, that a building at the bottom of Essex Street be purchased and used as an extension, and that separate reading rooms be set apart from the main building. These solutions would require considerable expenditure and never came to fruition, despite the suggestion of the purchase and demolition of the building in Essex Street by Lord Rothermere during a visit to the Library in October 1928. Rothermere also offered to supply 'anything which is wanted for the Library at any time', but due to his already great generosity towards the Inn, the Library Committee felt that it would not be right to ask for any further donations towards the expansion of the library.

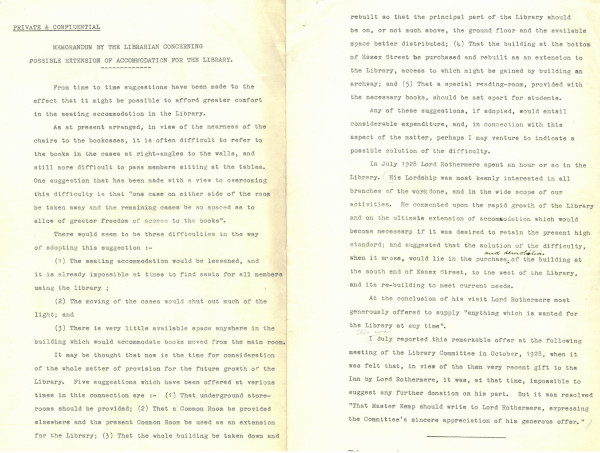

Memorandum by the Libarian concerning possible extension of accommodation for the library, March 1933 (MT/9/LIB/69)

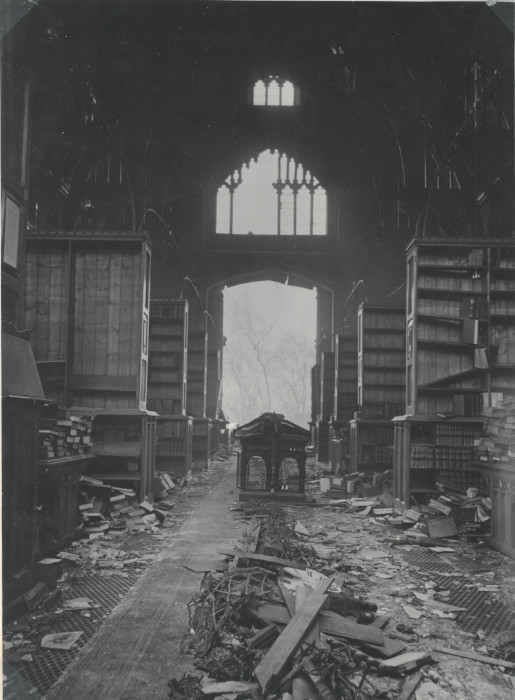

The Victorian Library at the Inn was dealt a fatal blow during the bombings of the Second World War. The structure was badly damaged by a bomb falling twenty feet from the south-east corner of the library on the night of the 8-9 December 1940, destroying the south Oriel window and blowing out all of the stained glass windows. Although the building was rendered unstable, temporary fixes were implemented to make the structure usable. However, the fate of the library was sealed by a flying bomb that fell on the 24 and 28 July 1944 to the west of Essex Street, which rendered the entire remaining structure unsafe – the roof timbers were fractured, rafters were torn apart and tiled portions of the roof were stripped bare. Additionally, cracks appeared in many places, temporary windows and doors were smashed and floors were lifting. After this attack, the library was temporarily relocated to the Inn’s Common Room and would remain there until a more practical temporary Library was opened in 1946. The Victorian library was condemned and remained roofless for some time before being demolished in 1954.

Photograph of destruction caused by a bomb exploding near the south-east corner of the library, 10 December 1940 (MT/19/PHO/5/10/1)

While many of the ancient buildings of the Middle Temple survived the destruction of the Second World War, the library, a building of distinctly Victorian monumental design, could not be to be salvaged. While its destruction was lamentable, it meant that a library more suited to the modern age, the needs of its members and the expansion of its collection could be constructed. The new library was built to the north of the Plowden Building and the Queen Elizabeth Building was constructed on its previous site. However, the ghost of the grand old building can still be seen in the staircase to no-where that overlooks the Middle Temple Garden. This used to lead to the library’s entrance and now only provides a tantalising hint to visitors about the existence of this forgotten edifice.

The Victorian library with its upper storey missing, 1950s (MT/19/PHO/5/17)