While the Middle Temple is, and has always been, a place of education and work, it is also home to a strong residential population living within many of its chambers. Life at the Inn has changed over the centuries, as has its population of residents. Initially chambers were the preserve of members and Benchers but at various points in the Inn's history, they have been opened up to house a range of non-members and tradespeople. This mix of tenants brought about a vibrant way of life on the Lane, but it was not without some conflict.

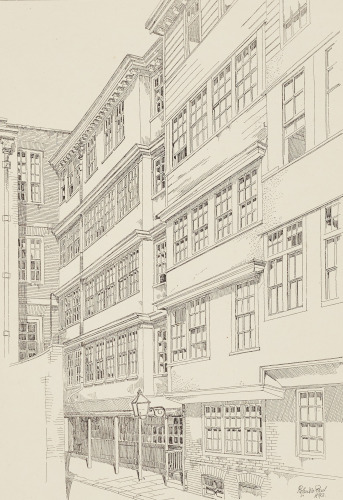

Middle Temple Lane Chambers, c. 1893 [MT/19/ILL/E/E8/6]

Brief History of Renting at the Inn

Walking through Middle Temple today, one sees the many buildings, containing chambers which are primarily used as the offices and workspaces of barristers-at-law and their clerks. However, historically, chambers played a dual role, as both a home and as a workplace. Members joining the Inn during its early centuries were expected to take up chambers within the Temple, either with an established Bencher or on their own. Chambers were initially only used by members of the Inn and therefore, as only men were permitted to join prior to 1919, were considered the preserve of ‘gentlemen’.

It was said by Reverend Alexander Simpson of Temple Church in 1613 in a letter to King James I, and agreed to by the Treasurer of Middle Temple, that he considered it better for members not to have women or children residing among them, even for those who were married. It wasn’t just the families of members who were discouraged from living within the Inn, an Order from the Inn’s Parliament on 26 June 1612 stated that “if any gentleman should suffer any Stranger to lodge in his Chamber, he should pay five pounds for the first offence and for the Second offence the Treasurer to admit another to his Chamber”.

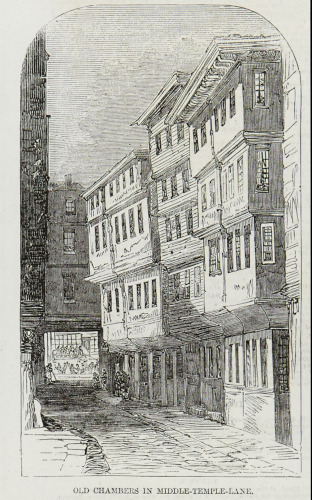

Old Chambers in Middle Temple Lane [MT/19/ILL/D/D8/28]

As time went on, preventing members from bringing their families to live with them in chambers proved near impossible and, by the 1700s, there were quite a few women and children residing inside the Temple. However, this was disapproved of by the Inn's Parliament, who passed Orders to prevent this from occurring. On 18 June 1708, the Inn brought in an Order for the removal of families from the Inn and forbade officers/tenants from letting their families into chambers.

Nevertheless, this did little to quell the growing number of women living at the Inn who eventually became an accepted feature at the Middle Temple. Although the Inn began to accept that women would now live at the Temple, there was still a disapproval on the idea of allowing them to rent a chamber in their own right as the lead tenant. One example of this discontent at having females living as tenants was seen when in 1785, Elizabeth Horsfall, the widow of the late Under-Treasurer James Horsfall, sought permission to remain in Lamb Chambers Building where she, her husband and six children had lived for the last sixteen years. Her appeals were rejected by Parliament, and it was decided that she must vacate the property by Christmas of that year.

During the 18th century, chambers began to open up to more people without any connections to the Inn who came in to take up available residences at Middle Temple, creating a diverse mix of tenants within the Temple. However, not everyone was happy about these developments as in 1769, a Vacation Parliament (a breakaway assembly of Barristers and members under the Bar who held their own Parliament during the vacations and presented their proceedings to the Bench Parliament) deplored the presence of the “lowest handicrafts of various kinds, who nestle here… milliners, mantua markers, laundresses, gamesters, prostitutes…”

Lantern Slide Image of Brick Court, 1774.

Some of the Inn’s tenants had more creative ways of using their residential chambers, opening them up to create museums, displaying objects which they had collected from around the world. Elias Ashmole, admitted 1657, who went on to found the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford was one such person. The items in this museum begun when his was living in his Middle Temple chambers and started to collect items from across the globe. Another tenant was William Courten (alias Charleton), a non-member, who accumulated a range of miscellaneous objects which he decided to display in a museum based at his Middle Temple chambers in Essex Court which he sub-let from a ‘Mr Earle’ in 1684. Little is known about the museum except from reports made by visitors such as John Evelyn who commented in his diary that: "I went againe to see Mr. Charleton's Curiosities both of Art & nature: as also his full & rare collection of Medails: which taken alltogether in all kinds, is doubtless one of the most perfect assembly of rarities that can be anywhere seene.”

Portrait of Elias Ashmole [MT/19/POR/22]

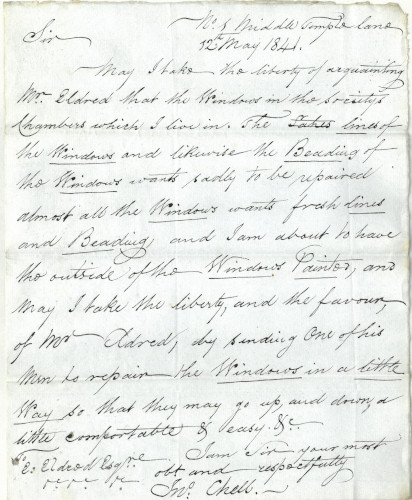

During the 18th and 19th centuries, chambers began to feel the effects of their sustained use by tenants over many years and in 1854, the Inn’s Treasurer, Charles Whitehurst, stated that the “Chambers in the Middle Temple are in a wretched condition; they are old and must almost all come down.” The archives hold numerous letters from tenants asking for repairs to be made to their chambers. For example, in 1890, a Mr Geary of No 2 Pump Court wrote a request to the Society asking them to undertake a repair to the sash windows in his chambers, which was agreed to and returned with a Surveyors Report accepting these changes. Earlier, in May 1841, a Mr Chell had put forward a firm complaint regarding the windows in his building which were in desperate need of repair. He stated that “almost all of the windows want fresh lines and beadings” in order that he might comfortably open and close them.

Window Complaint, 1841.

In the 19th century, to modernise chambers and improve their tenants' quality of life, the Inn proposed the introduction of gas lighting. However, this was not without worry, as in 1847, a William Chamberlayne who owned Chambers 1 & 2, Middle Temple Lane, wrote to the Inn raising his concerns about the introduction of gas lights to chambers due to the high cost associated about the cost. Gas light also wasn’t perfect, as in 1875, a Mr H. Lyengo wrote to the Under Treasurer stating that the gas light in his chambers was insufficient and that he required further light to be installed.

As technology advanced further, tenants in chambers looked towards the introduction of electricity to replace their gas supply; a letter from Frank Hicks of No 1 Garden Court, written in 1897 to the Surveyor, asked for electric lightbulbs to be introduced to his chambers. Later in 1906, a Mr Harald Balten wrote asking for permission to install electric lighting outside of his chambers at 3 Temple Gardens to improve the visibility at night.

During World War II and the Blitz, large swathes of the Inn were hit by bombs, destroying many chambers buildings, and creating a need for rebuilding and restoration to provide habitations for members and tenants.

View of Middle Temple after damage during the Blitz.

More recently, a new tenant came to the Inn in the form of the Belgium Olympic Federation who made Middle Temple their home during the London 2012 Olympic Games, creating a “Belgium House in London”. This House and the Belgian Cycling Paradise were an initiative of the Belgian Olympic and Inter Federal Committee (BOIC). Their takeover of the Inn was open to the public to come in and watch the Olympics on a giant screen with refreshments on offer, including beer sold “perhaps at the most attractive prices in the city.”

Inventories of Chambers

A great deal of the knowledge we have about how people lived at the Inn is derived from records which survive in the Archives. One type of record which gives an in-depth view of life in chambers are the numerous inventories of various rooms occupied by members during their time residing here, spanning from the 1600s to 1800s.

Some of the earliest inventories of chambers come from the 1600s, such as the inventory of Robert Ashley’s chambers which was collated on 25 July 1646. Some of the things included in it are:

One large Bedstead

Three tables

Five high stools

Robert Ashley's Chambers Inventory [MT/5/CIV/1]

Inventories were continually kept by the Inn, for example in 1723, a book titled ‘Bench Chambers Survey and Inventory’ was produced which detailed the furniture of lodgings of many Benchers. Similar items were in the possession of these Benchers across their various chambers, showing what it was common for a Barrister of Law to own in their home. For example, one inventory of Elm Court, taken from this book, shows some of the possessions owned by a Mr Edwards:

a desk bed

a cupboard with shelves over the desk

draws

a small iron lock to the door going into the desk

a large cupboard with shelves folding doors and lock

Inventory of Mr Edwards' Chambers at Elm Court.

The staple pieces of furniture within a chamber inventory do not change much over the years, as records for chambers in the 1800s show, with an expansion in the amount of furniture included and a wider variety of crockery.

For example, an inventory from 1821 of a George Barker residing at No. 3 Church Court, Temple holds a rather detailed inventory on the furniture he possessed in his home.

A […] stove set and marble fittings

A large deal bookcase with sliding shelves and doors

A small deal cupboard lock and key

A washing stand mahogany

A knife board

Inventory of George Baker, 1821 [Box XCII - Bundle VI - 5]

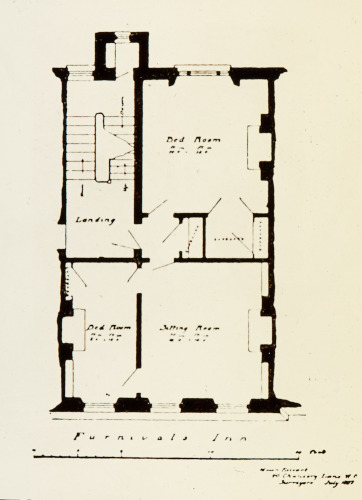

A later inventory of furniture and fixtures at No. 1 Middle Temple Lane was divided up by room and includes reference to items such as curtains and hat pegs.

Bedroom

[…] Rack

Hat pegs

Brackets

Curtain pole

Drawers with marble slab

White marble slab

Back Sitting Room

2 sets of Bookshelves and cupboard

Vallance (decorative drapery attached to the curtain pole) and curtains

Fire gate

Plan of a Chambers at Furnivals Inn, 1881.

These inventories give an insight to the types of furnishings people had within their chambers, showing both the continuation of ownership over similar items, but also the gradual expansion of household items which people owned.

Conclusion

Overall, life in a residential chamber on Middle Temple Lane is now a very different experience to that which it would have been when the Inn first began renting out rooms. Although most buildings within the Temple are now used primarily for professional purposes, those residents who do still call the Inn home are part of a rich tradition over many centuries.