The 26th January 1679 was a bitterly cold Sunday. The Thames had frozen over, icicles hung from the eaves of the houses and a fierce wind blew through the streets. It is easy to imagine that, after attending to the necessity of church on the sabbath, the residents of the Temple would have retreated into their chambers to huddle before their fires, little imagining that they would dramatically be forced to flee after the unattended embers from one fire spilled from its grate, setting alight a chamber three floors up in Pump Court, at around 10 o'clock in the evening.

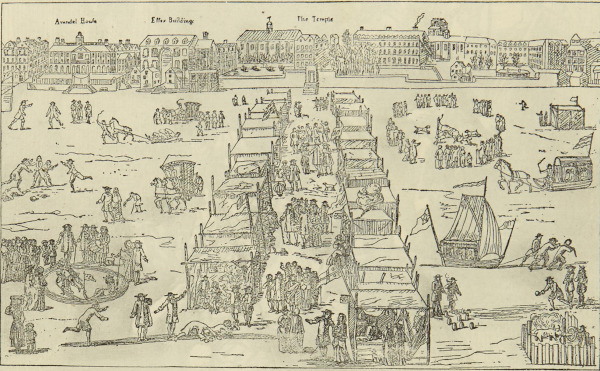

Print of a Frost Fair on the frozen Thames with the Temple in the background, 1683 (MT/19/ILL/D/D8/16)

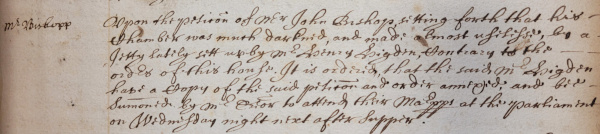

The devastation wrought by the Great Fire of London in 1666 would have been fresh in the minds of the Templars and the surrounding residents of London. Numerous chambers in Inner Temple had been destroyed by the Great Fire, but its progress was halted before it could reach any of the Middle Temple buildings. The chambers, untouched by the previous fire, would probably still have been remnants of the medieval style of building with wooden exterior walls – a style that had been banned in the City due to its inability to stop the spread of fire. The upper stories would have been constructed with jettying, meaning they overhung the lower stories, bringing the buildings close together and enabling the fire to spread more easily. Eyewitness Roger North (1653-1734), also attributes the growth of the fire to the amount of ‘deal’, also known as fir of pine, used in the interior fittings and decoration in the chambers, which was much more combustible than woods such as oak.

Complaint about a jetty constructed by Mr. Henry Higden that made a neighbouring chamber ‘much darkened and almost useless’, 23 November 1666 (MT/1/MPA/6)

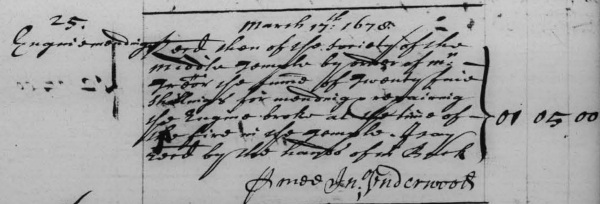

Firefighting was made especially difficult by the weather conditions at the time. Human bucket chains were made from the river, where it was difficult to access the water as it was frozen over. Water apparently froze in the buckets as they were being carried to the fires and in the fire engines. Water pipes were broken in the street and the stream of water that was released froze as it flowed down the lane. As well as the bitter cold impeding the progress of those fighting the fire, the high winds helped to spread the flames by providing a ready source of oxygen, and the fact that it started high up in a building and spread across the roofs meant that those fighting the fire were not able to climb on to those roofs and douse the flames from above.

Receipt for repairing a fire engine ‘broke at the time of the fire in the Temple’, 17 March 1679 (MT/2/TRB/37)

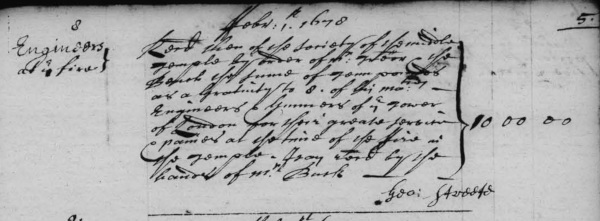

One strategy employed for containing the spread of the fire was to blow up particular buildings to create a firebreak. Great efforts were made to save Middle Temple Hall as, in the words of North, ‘which burned had been an irreparable loss, almost to dissolve the Society’. In order to save the Hall, gunpowder was applied to the corner of Elm Court, but the building was of such solid construction that two explosions failed to bring it down – the Hall was saved only by a ‘double party wall and stack of chimneys’, which prevented the spread of the fire at that corner. The safety of Fleet Street was also of great concern and it was ordered that the adjoining buildings be blown up to save it – these buildings proved less resistant than the corner of Elm Court and collapsed in a shower of rubble. Many of the injuries from this fire came from fulling masonry caused by explosions, including those of the Earl of Feversham, who was hit on the head by a falling beam and had to undergo invasive surgery on his skull known as trepanning in order to survive the incident.

Receipt for payment to ‘Engineers & Gunners of the Tower of London for their ‘great service and pains at the time of the fire’, 1 February 1679 (MT/2/TRB/37)

The fire was finally extinguished at around midday the following day and by that time the Middle Temple had been utterly devastated. Pump Court, Hare Court, Essex Court, Brick Court, Vine Court, Hall Court and part of Elm Court were destroyed, and the Cloisters had collapsed on itself in a spectacular fashion, spreading embers over watching crowds and setting their clothing smouldering. The roof of Temple Church caught fire, though it was quickly extinguished, and the Inner Templars, overzealously in North’s opinion, had blown up their own Library. Despite the destruction of many of the Middle Temple’s buildings, most of the residents managed to remove their belongings before the fire reached them – the exceptions to this being the staircase in which the fire started where residents barely had time to clothe themselves before making their escape, the contents of the Fine Office, which was blown up along with all of their records, and a great portion of the collection of rarities, in the possession of the antiquary and Middle Templar Elias Ashmole, originally assembled by John Tradescant.

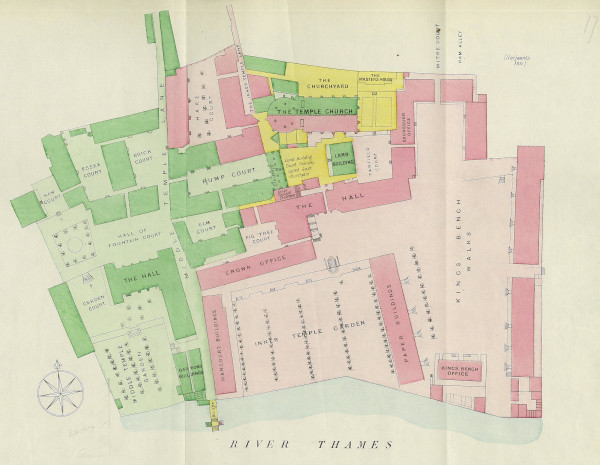

Plan of the Temple from John Ogilby’s map of London, 1677, with the extent of the Temple fire shown in Green on the left and the Great Fire of London in red on the right

The members of the Middle Temple, looking around at the smouldering ruin of the fabric of their Society, then had to find the means to rebuild. Clearing and reconstruction work quickly started in the precinct and one ‘decrepit old woman’ was heard to wryly comment when looking at the construction efforts of the lawyers, ‘Well, I see ill weeds will grow fast’. However, the path to reconstruction was not without its impediments, and the eventual settlement was the result of careful negotiations between the interests of the Benchers and those of the membership – the latter being unable to rebuild their own chambers without providing for the construction of the Bench chambers and the former being unable to finance the rebuilding of the chambers on their own.

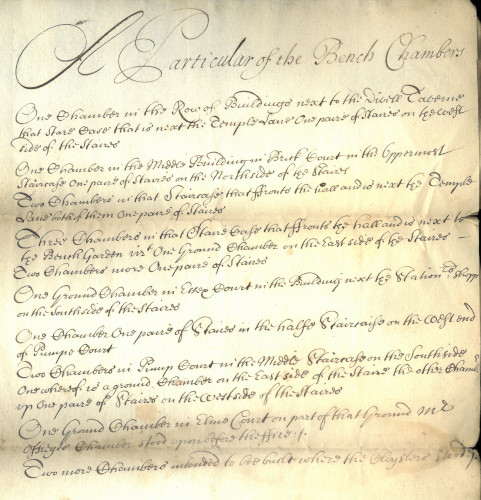

Particulars of the new Bench Chambers under construction, 1679 (MT/21/1/46/2/5)

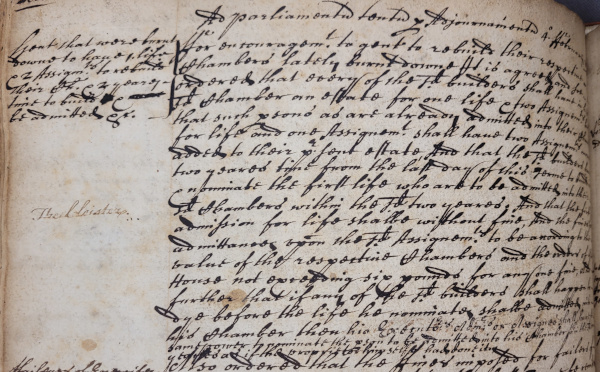

The fear of the terms that the Benchers might impose on them unified the membership, and they formed their own Parliament to represent their interests and assert their right to rebuild instead of the Benchers, with one person from each staircase nominated to represent the interests of the residents of that staircase. The result of the negotiations was that the members of the Middle Temple would finance the rebuilding of their own chambers and in return they would be granted more favourable arrangements for their lease and its management'?

Order of the Inn’s Parliament that any gentleman who rebuilds his burnt down chambers be granted an assignment for life to the chambers and two assignments afterwards, 4 February 1679 (MT/1/MPA/6)

It was decided that the new Middle Temple chambers would be rebuilt to new plans rather than being directly built on the old foundations. However, a precise plan for new buildings could not easily be agreed upon, as each member fought for the representation of their own interests in the designs. North characterises those attending the meetings as looking to find fault, rather than seeking to come to an agreement. The deadlock was finally broken by the property developer and speculator Dr. Nicholas Barbon, who was highly skilled in persuasion and manipulation, and was able to get the membership to agree to his scheme through appealing to their individual interests. He created a model and proposed that each member would have the same amount of land that they had prior to the fire, and anything above that they would pay for at a set rate. He then had the members put their names on the ground plot of his model with the number of storeys high their chamber would be. Barbon’s methods soon broke the deadlock that had formed and allowed progress on rebuilding to commence.

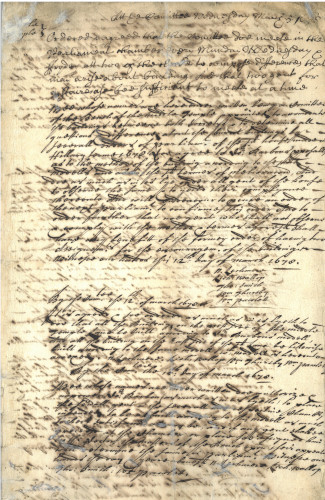

Orders of the committee for rebuilding the Middle Temple after the fire there. Includes agreement to Dr Barbon's proposals, 1679 (MT/6/RBW/14)

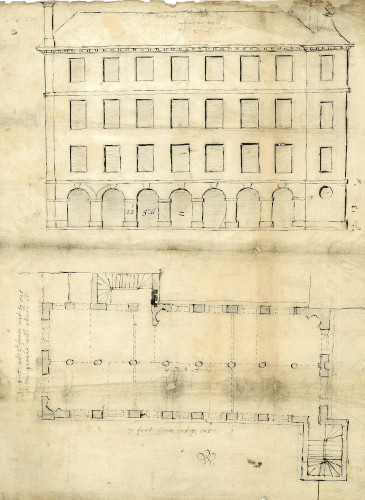

Progress on the Cloisters started later than other buildings as it required the Middle Temple to come to agreements with the Inner Temple, which were only settled through the arbitration of the Lord High Chancellor of England. Nicholas Barbon was first approached about the project in July 1679, and had come up with a design by June 1680 that was accepted by the membership. However, in October 1680 the committee that had approved Nicholas Barbon’s model reconsidered and chose a design created by the famous architect, Sir Christopher Wren. Wren wrote a critique of Barbon’s plans, stating that they were ‘too weak and insufficient’ due to pillars of too small diameter and too far apart ‘either for beauty or necessary strength’, the floors were too wide for the strength of the walls and the chimneys were not safe against fire, with key aspects of their design being planned to be made of the more flammable deal wood. Despite the rejection of his design and the fact that he was ‘wanting money’ and as a result ‘materials were wanting or came very thin’, Barbon was still approached to oversee the construction of the new Cloisters building.

Plan and elevation for the Cloisters produced by Sir Christopher Wren, 1680 (MT/6/RBW/18)

The 1679 Temple fire was a cataclysmic sequel to the Great Fire of London for the Middle Temple. After being spared from destruction in the former disaster, the Middle Temple had to contend with the challenges faced by the City of London and the Inner Temple thirteen years before. However, the disaster presented the Inn with the opportunity to modernise its architecture and created the street plan that is still in use today. Additionally, the subsequent negotiations created a sense of solidarity within the membership and brought them together in a common cause. In the words of North, ‘[the model] was delivered into the Treasury as the act of the whole Society, and was the happiest resolution of a perplexed touchy affair that I have known, and the present prosperity of the Temple is owing to the fortunate circumstances of it’.

Plan of the Temple after being rebuilt, 1732 (MT/4/5)