The Middle Temple Gate, also known historically as the ‘Great Gate’, stands at the top of Middle Temple Lane and guards the Fleet Street entrance to the Inn. It has throughout history provided carriages and pedestrians with their first impression of the Society and is one of the most distinctive markers of the boundary between the Temple and the rest of London. Despite being demolished and rebuilt several times over many centuries, it has continued to serve the important function of enabling the Society to defend and maintain control over its property, although sometimes with mixed success.

Print of the Middle Temple Gate and Temple Bar, 1800 (MT/19/ILL/E/E12/14)

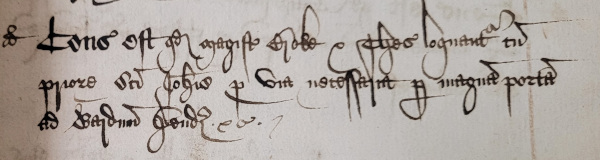

The oldest known record of the gateway appears in documents dating from 1337, in the first few decades of the lawyers’ tenancy at the Inns of Court. It was the main entrance into what was called the New Temple at the time, a name which encompassed the lands of the Templars after they moved from their old site near Holborn. No known description of this gate survives, but there are glimpses of it in the Society’s earliest records – such as in an order dated 2 November 1506 that Master Broke and the Treasurer should talk to the Prior of St. John’s, the Inn’s landlord at the time, ‘for having a necessary way through the great gate to the garden’ and of 2 November 1508 regarding taking advice about ‘the building of William Arowsmyth within the Great Gate, which is a nuisance’. It is unclear in this instance whether the record was referring to construction work within the gate itself, or just within the Temple precinct beside the gate.

Order of the Inn’s Parliament to request a way through the great gate to the garden from the Prior of St. John’s, 2 November 1506 (MT/1/MPA/1)

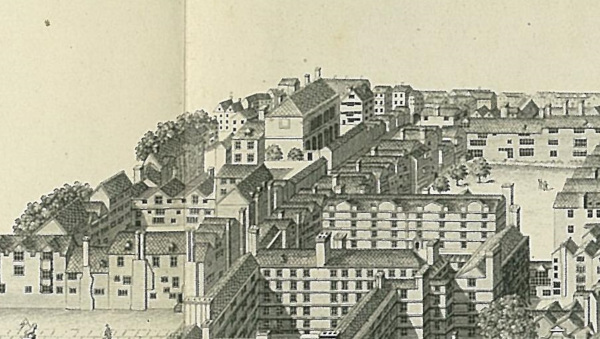

The gatehouse was rebuilt in 1520 by the Treasurer of the Middle Temple, Sir Amyas Paulet, at his own expense. Paulet resided in chambers above the gate of the Middle Temple for five or six years having displeased Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Lord Chancellor (1515-1529), who ordered him not to leave London without his permission. Paulet had offended Wolsey by putting him into stocks when he was a young man, and he subsequently attempted to appease the cardinal by emblazoning the Great Gate with cardinals’ hats, arms, badges and other devices celebrating Wolsey. The only surviving depictions of this date are either of questionable accuracy or of extremely limited detail. A crenulated structure is shown in the Agas Map, the earliest complete map of London dating to around 1561, but this may have been a symbolic depiction of the gateway. The few details visible of the gate in a 1671 print of the Temple show no crenelations, but there may have been alterations to the gate between 1520 and 1671.

Depiction of the south side of the sixteenth century Great Gate in a print of the Temple, 1671

This structure remained in place for around 150 years and survived both the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the Temple Fire in 1679 that destroyed a great number of chambers. Despite this, it appears that the Benchers of the Inn were dissatisfied with the entranceway - the reasons are unknown, as it was not described as 'ruinous' or in 'decay' like other buildings in contemporary records. Nonetheless, a committee of Benchers was asked to view the Great Gate and report on the potential for its rebuilding at the next Parliament. There is no record of such a report ever having been made, and no action was taken regarding rebuilding the gate for almost two decades.

Plan of the Temple from John Ogilby’s Map of London, 1677. The red line shows the extent of the Great Fire of 1666 and the green line the extent of the Temple fire of 1679.

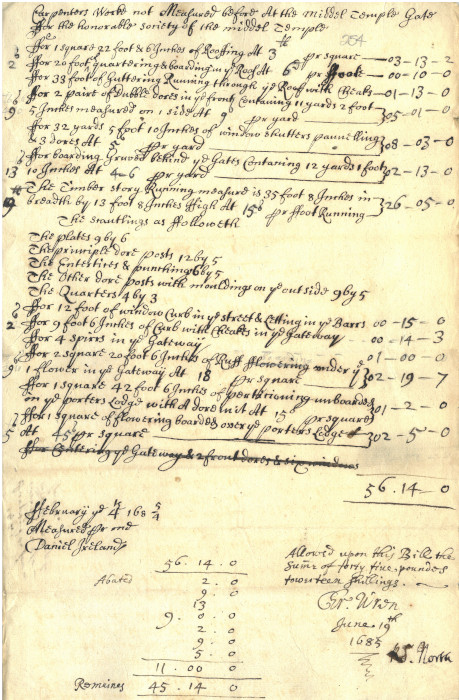

The first renewed stirrings of this project occurred in the Parliament of 25 January 1684, where the Treasurer Roger North was asked to report his opinion on it at the next session. No official permission was granted for the commencement of the work by the Inn’s Parliament, but on 6 February 1685, the famous architect Sir Christopher Wren and Roger North paid a mason and a carpenter for work on the Great Gate. The original receipts for the building work survive and include a detailed summary of the work completed on the gate. They are signed by both Roger North and Christopher Wren and appear to have been settled quickly, in contrast to building projects earlier in the century, as the last mention of a ‘schedule of debts’ owed by the Inn appears in the Parliament of 19 June 1685.

Receipt for the work of the carpenter on the Great Gate, signed by Sir Christopher Wren and Roger North, 1685 (MT/2/TAP/11)

Wren’s involvement in the project was not in the capacity of an architect, as was the case with the refurbishment of Temple Church and the rebuilding of the Cloisters, but as ‘surveyor’ and a practical expert. According to a 1959 newspaper article, this is proven in a manuscript essay by Roger North entitled ‘Building’ that currently resides in the British Library as one of twenty-four manuscript volumes in North’s own hand. This manuscript allegedly explains in detail why North designed the features of the Middle Temple Gate as he did, and why he did not always follow the advice of Wren.

Portrait of Roger North after Sir Peter Lely, oil on canvas, based on a work of 1680 (NPG 766) © National Portrait Gallery, London

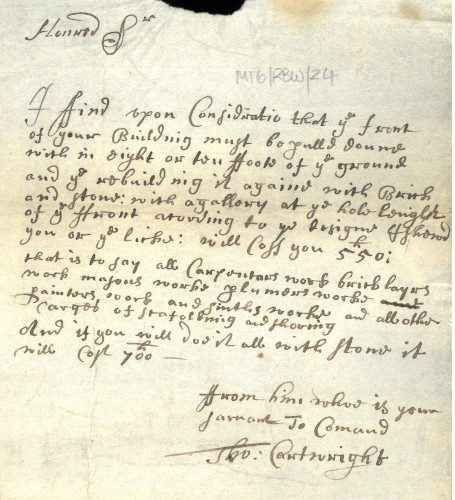

North was a great polymath and appears to have been keen to rise to the challenge of designing the new building, however there were other architects that wanted to be involved in the project and pitched their own designs. The mason and architect Thomas Cartwright - who was previously employed to work on Temple Church and was the architect responsible for projects such as St Thomas’ Hospital and St Thomas’ Church - wrote to Master Northey to provide quotations for a building of ‘brick and stone: with a gallery at the whole length of the front according to the design I showed you or the like’ and for a more expensive version of the building all in stone. The Treasurer's receipts, however, offer no evidence to suggest that Cartwright was in any way involved with the Middle Temple Gate project.

Note from Thomas Cartwright, mason and architect, offering quotations for building the Great Gate, c.1683 (MT/6/RBW/24)

The new balcony at the gate may have been designed to provide the Benchers of the Inn with a viewing platform for processions and events passing by the Temple in Fleet Street. Previously the Inn paid to have scaffolds built at the top of the lane, such as during the coronation procession of King Charles II. When it was built, the chamber above the gate was rented out with the express stipulation that the Benchers retained the right of access for viewing various ‘solemnities’, which was both more convenient and economical than the previous arrangements. The balcony has been used to view many such occasions since its construction; the state entry of the new King George I into London on 20 September 1714, Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession in 1897, and State funeral of Sir Winston Churchill on 24 January 1965, to name just a few.

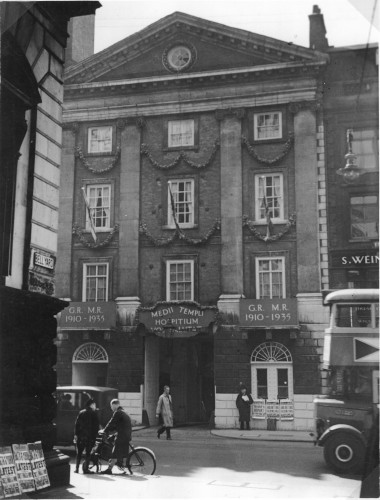

Photograph of the Great Gate during the celebrations of King George V’s silver jubilee, May 1935 (MT/19/PHO/10/11/1)

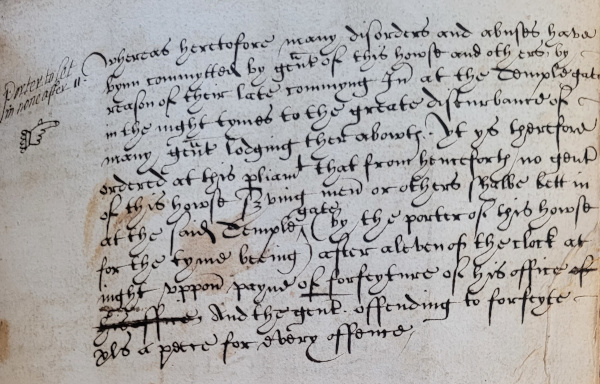

Although the use of the gate as a viewing point was a great benefit to the new design, its primary functions remained to act as a boundary of the Temple and to keep both Societies and their residents safe in times of war and strife, as well as providing the means to prevent criminal behaviour by ‘strangers’ from upsetting the peace of the residents. The gates of the Middle Temple were closed at prescribed times, setting a curfew on all of the residents in chambers. The first order regarding the closure of the gate at particular hours appears on 6 February 1607 when ‘no gentlemen of the House, serving men or others shall be let out of the Temple Gate after 11pm on pain of the Porter’s forfeiting his office, and a fine of 40s. for the person let in’. To allow the Porter to discharge his gate duties more effectively, a small parcel of ground under the gate was granted for the use of Philip Walker, the Porter, on 25 October 1611. By 1612 this was referred to as the ‘Porter’s Lodge’.

First order relating to the closure of the gate at prescribed times, 6 February 1607 (MT/1/MPA/3)

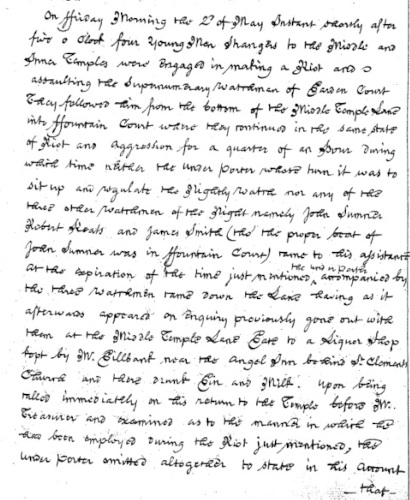

It appears that the curfew imposed on the residents of the Inn was relaxed at some point as the next mention of it was on 23 June 1671 when it was ordered that ‘in consequence of the outrages and tumults committed for several nights past upon the watch at Temple Bar, an order made 25 November 1614, forbidding the Porter to let any one in or out of the Temple Gate after 11pm on pain of dismissal, is revived’. Stricter regulations, closing the gate at 9pm, were put in place for the first time over Christmas of the same year, probably to try to prevent traditional Christmas disorder, and continued until 1678, with the order being revived with generous extension to 10pm in 1683. Curfews only became more rigidly enforced with the rise in crime in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, though sometimes the Porters and the Watch could be negligent in their duties. This is demonstrated by an incident on 2 May 1828 when four young men got into the Temple at 2am, made a ‘riot’ and assaulted attending watchmen. As a result of this incident, the security of the Middle Temple was overhauled and regulations over the opening and closing times of all gates were strengthened, much to the chagrin of nearby tradesmen whose businesses were impacted by the rules.

A report regarding a security incident at the Temple on 2 May 1828, 16 May 1828 (MT/1/MPA/12)

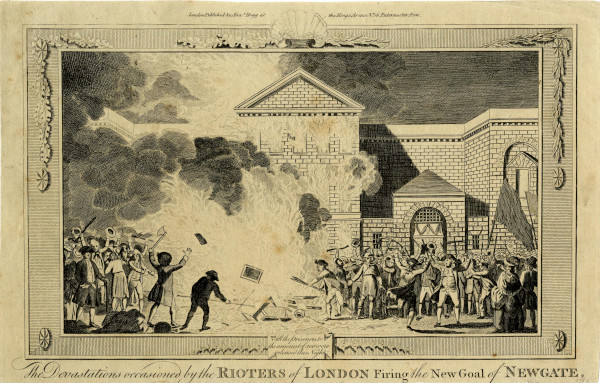

As well as preventing general criminality, we know of at least one incident in the Temple’s history when the gates helped to protect the Inn against an angry mob. The earliest gate failed to protect the Temple from sacking and murdering during the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381, which burnt law books, buildings and killed anyone associated with the royal government. The modern gate withstood the Gordon Riots of 1780, several days of rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. During one of the nights of rioting, a mob descended on the gate and knocked out one of its panels but were beaten back by the Northumberland Militia. For the remainder of the rioting, the gates of the Temple were shut up and barricaded with large paving stones and guards composed of students were formed turning the Temple temporarily into a fortress.

Print of Gordon rioters burning of Newgate Prison, 1781 © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Middle Temple Gate was the only gate belonging to the Society that provided access to carriages and carts, and was instrumental in controlling the flow of traffic at the Inn. Even several centuries ago traffic was considered to be a problem, as shown by an order of 20 May 1631 that stated ‘to prevent the trouble of coaches in Middle Temple Lane, whereby passengers are hindered in their passage too and fro about the House and to and from the Watergate; the Porter shall keep shut one of the leaves of the great gate… and attend there to open it for carriages for the use of this House or the Inner Temple’. There were further problems with traffic in 1637 and the Porter was ordered to ‘attend the more diligently about the said gate, to keepe out strangers’ coaches and that the lane be not pestered therewith’.

Hackney coaches and foot traffic on Fleet Street outside the Middle Temple Gate, c.1760 (MT/19/ILL/E/E12/2)

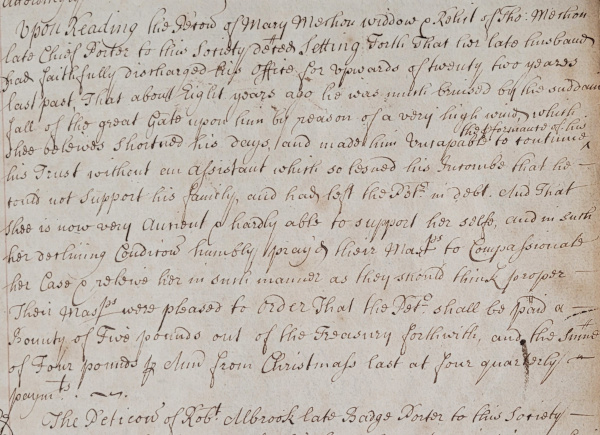

While the Great Gate could be a great protector of the Middle Temple, it also had the potential to constitute a hazard. On 8 February 1723 a petition was submitted to the Inn’s parliament from Mary Machon, the widow of the late Chief Porter, Thomas Machon. He had been in office for 2 years and around the year 1715 a high wind made the Great Gate to fall on him, which the widow believed had ‘shortened his days and made him uncapable to continue the performance of his trust without an assistant which so lessened his income so he could not support his family’. This had left his elderly widow in debt and she requested a one-off payment of £5 and the sum of £4 per annum. This was duly granted to her by the Society.

Record of the petition of Mary Machon, widow of Thomas Machon, late Chief Porter, who was injured by the Great Gate falling in a high wind, 8 February 1723 (MT/1/MPA/7)

The Middle Temple Gate of the present day, built by Roger North and Sir Christopher Wren over three hundred years ago, still serves the Society in its original function as a boundary and means of protection for the residents of the Inn. It also stands as a reminder of a period of profound upheaval and change at the Inn after the disaster of two destructive fires so close to each other at the end of the 17th century, and of the commitment of the Middle Temple to rebuilding and improving on what was there before.