'Shouting with inexpressible joy; the ways strew'd with flowers, the bells ringing, the Streetes hung with tapissry', wrote the diarist and Middle Templar John Evelyn of the mood in London on 29 May 1660. After eleven years of republican government and military rule, King Charles II had returned from exile to take his throne, and his procession through the City of London was met with exuberant, clamorous celebration. Fountains flowed with wine, fanfares were sounded at every turn, and the great institutions of the City hung their windows with banners and tapestries.

Beyond these immediate festivities, the Restoration of the Monarchy impacted society broadly and at all levels, and the Middle Temple was no exception. This month we discuss the effects of the Restoration on the Inn, from the rejuvenation of its social and educational calendar to the shifting aesthetic and political atmosphere.

Engraving of Charles II's triumphal entry into London at his Restoration © The Trustees of the British Museum

From Civil War to Restoration

The past eighteen years, following the outbreak of the English Civil War, had impacted the Inn in many ways. Much of its traditional collegiate activity had ceased: no Reading had been given since Autumn 1642, and under the rule of Oliver Cromwell the celebration of Christmas and the performance of plays had been officially curtailed and proscribed.

While the Benchers had been divided relatively evenly between the two sides in the struggle, many Royalists, such as Sir Peter Ball and Sir Richard Lane, had left London to join the King. One Middle Templar who had flourished under Cromwell was Sir Bulstrode Whitelocke, a former Treasurer of the Inn who served as a Commissioner of the Great Seal and Ambassador to Sweden. A prolific writer, his memoirs are an important source for our understanding of the age.

Bulstrode Whitelocke, Unknown artist. Oil on canvas, 1634. NPG 4499 © National Portrait Gallery, London

When the republican regime faltered following Cromwell's death in 1658, the governor of Scotland, General George Monck, had marched south and established a new Parliament in London. Meanwhile Charles II, in exile on the continent since 1651, issued the Declaration of Breda, in which he promised religious toleration and a general pardon for many of his erstwhile opponents, if restored to the throne. The Declaration had in part been drafted by Charles' Lord Chancellor, Edward Hyde (later Earl of Clarendon), a member of the Middle Temple whose portrait hangs in the Ashley Building.

Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon, attributed to Sir Peter Lely

Celebrations at the Inn

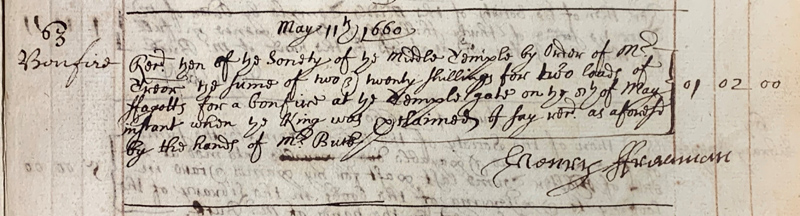

The first sign of the Restoration in the archival records of the Inn is a receipt for two loads of faggots (bundles of sticks) supplied as fuel for a bonfire on 8 May 1660 'when the King was proclaimed'. On that day, Monck's newly established Convention Parliament had issued a proclamation, read at Temple Bar just outside the Inn's gatehouse, that Charles II was king, and had been since his father's execution in 1649. Bulstrode Whitelocke recorded in his memoirs that 'the people gave loud acclamations and shouts, the bells rang... the City was full of bonfires and joys.'

Receipt for two loads of faggots for a bonfire at the Temple Gate when the King was proclaimed, May 1660 (MT/2/TRB/18)

Charles entered London on the 29 May, his 30th birthday, having landed at Dover a few days earlier. After crossing London Bridge, the route of his procession took him through the City of London, and the authorities and institutions such as the Livery Companies threw themselves into the celebration, no doubt keen to establish their Royalist credentials under the new regime.

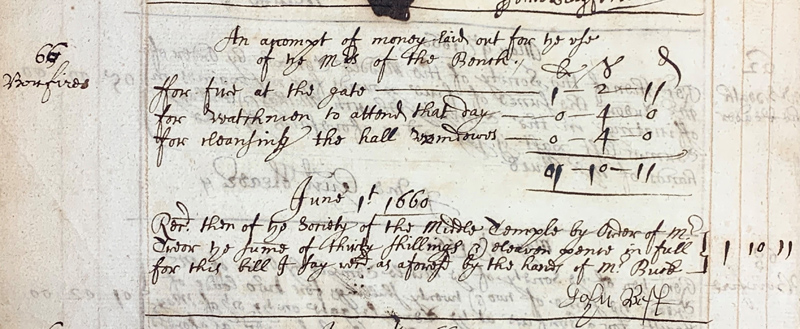

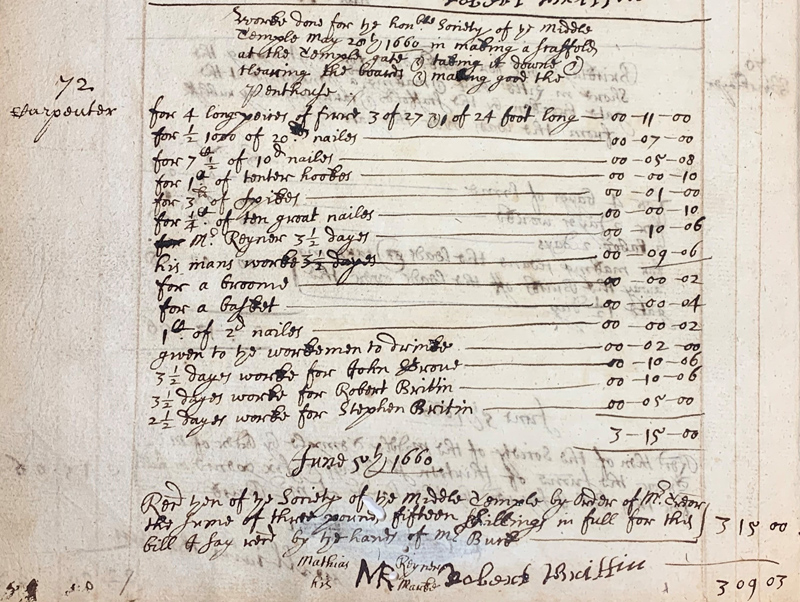

The Middle Temple was an eager participant in the festivities. A carpenter's bill dated 28 May sets out in detail the costs for 'making a scaffold at the Temple gate' - likely some sort of wooden stand from which to observe the procession and hang banners and tapestries. Bills exist for '5 pieces of hangings', cleaning the Hall windows, a 'fire at the gate', and for '8 white staves for the Officers'. Wine flowed from water fountains in the streets, and toasts were drunk to the King's health. Unsurprisingly, the mood of revelry grew more raucous and drunken as the day progressed, and extra watchmen were engaged to attend the Inn.

Receipt for a bonfire, watchmen and cleaning the Hall windows at the Restoration, May 1660 (MT/2/TRB/18)

Carpenter's receipt for the construction and dismantling of a scaffold at the Restoration, May 1660 (MT/2/TRB/18)

A year later, similar celebrations marked the King's coronation; progressing through the City from the Tower of London to Whitehall, Charles was once again greeted by cheering crowds, ceremonial arches, and even Morris Dancers, performing around a 41m high maypole on the Strand. The Inn threw itself once more into these festivities, lighting bonfires and displaying extravagant hangings to greet the King as he passed. A contemporary engraving depicts Charles on horseback on his way to Parliament, as well as Edward Hyde (on horseback to his right).

'The Most Magnificent Riding of Charles ye IId to the Parliement', 1661 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Social and Cultural Rejuvenation

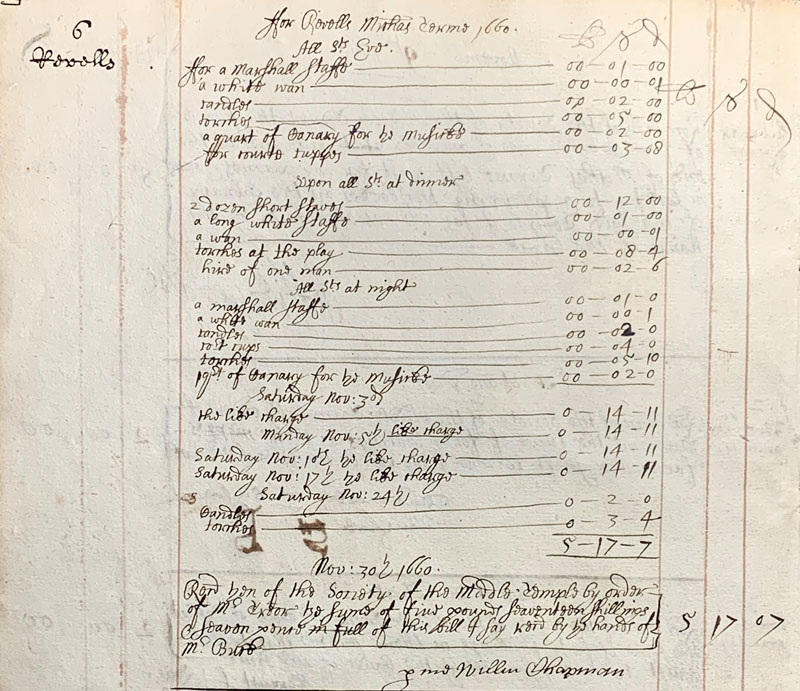

It was not, however, just through participation in these great public celebrations that the Middle Temple felt the effects of the Restoration. The Inn's social activity, which had been constricted in various ways under Cromwell, began to return to normality. The bill for Revels around the feast of All Hallows in Michaelmas 1660, for example, was £5 17s 7d, compared to £2 2s just a year before, encompassing sums spent on candles, wands, torches and Canary wine for the musicians. For the first time in many years, funds were approved for the 'encouragement' of those dining in the Inn over Christmas.

Receipt for Michaelmas Revels, November 1660 (MT/2/TRB/19)

Plays performed by the great London theatre companies of the day had once been a prominent part of the Inn's calendar, usually at the Grand Day feasts for Candlemas and All Hallows - including, most famously, Shakespeare's Twelfth Night at Candlemas 1603. Theatre had been suppressed under Cromwell, but with the return of the King, personally a great lover of the theatre and keen to win over his subjects, plays could once again be performed to eager audiences.

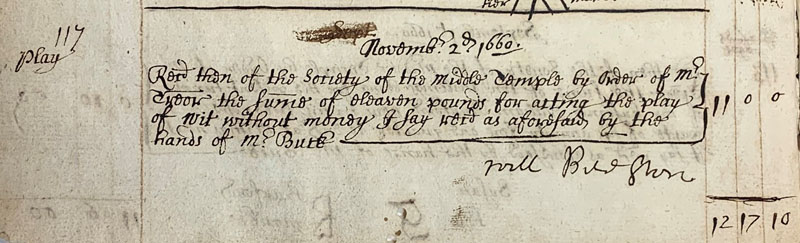

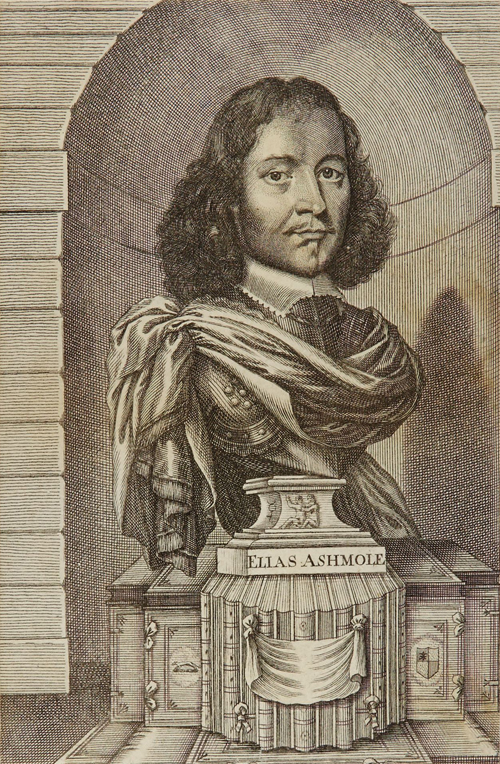

The Inn evidently seized upon the opportunity, as a receipt dated shortly after the feast for All Hallows, records the payment of £11 to one Will Burgon 'for acting the play of Wit without money', a popular comedy by the Jacobean playwright John Fletcher. The antiquary and Middle Templar Elias Ashmole also records this occasion in his diary, recording that Edward Hyde had attended the feast preceding the performance.

Receipt for the performance of 'Wit Without Money', at the All Hallows' feast, November 1660 (MT/2/TRB/18)

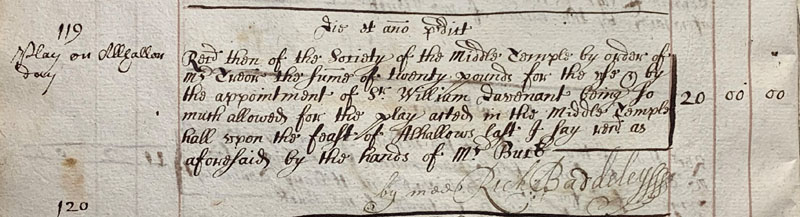

Receipt for the performance of a play at the All Hallows' feast, November 1661 (MT/2/TRB/19)

To encourage - and manage - this theatrical renaissance, in August 1660 the King licensed two new theatre companies: the King's Company and the Duke's Company, the latter led by William Davenant, who had been Poet Laureate under Charles I and taken the Royalist side in the Civil War. A receipt from November 1661 records the payment of £20 'by the appointment of Sir William Davenant... for the play acted in the Middle Temple hall upon the feast of Alhallows last'. The play's title is not noted, but may have been Davenant's own Love and Honour, which Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn both record having seen that Autumn in their diaries.

Engraving of William Davenant, frontispiece to his 'Works' (London, 1672). © The Trustees of the British Museum

Art & Commemoration

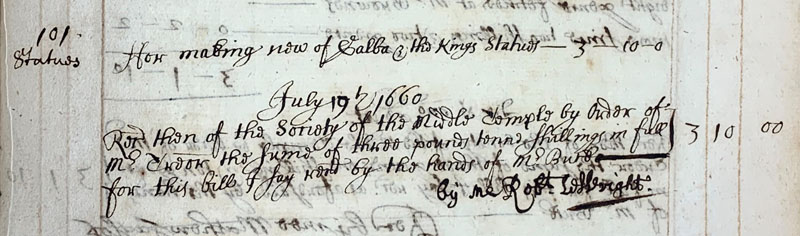

The aesthetic environment of the Inn also changed in telling ways, as the Middle Temple authorities hurried to demonstrate and communicate their support for the new regime. Within weeks of the King's arrival in London, the accounts record £3 10s paid to one Robert Wright for 'making new of Galba [a Roman Emperor] & the King's statues'. This new statue, likely a bust of the King, does not survive in the Inn's collections.

Receipt for the making of a new statue of the King, 1660 (MT/2/TRB/18)

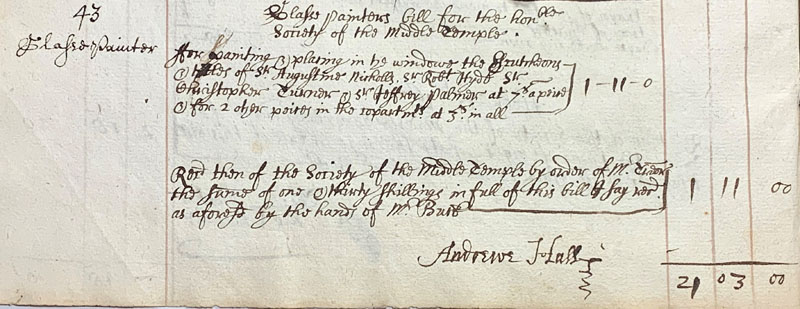

Shortly afterwards, the Inn also paid one Andrew Hall for producing new stained-glass windows in Hall for Sir Robert Hyde, Sir Christopher Turnor (Treasurer 1662) and Sir Geoffrey Palmer (Treasurer 1661), all Royalist Middle Templars who had been appointed to high judicial office at the Restoration. These windows can still be seen in Hall today. A receipt also survives for a sum paid to Baptist Sutton for putting up the King's Arms in the glass of Temple Church. Sutton was considered one of the greatest glass painters of the period, and undertook work for the Inn on many of the heraldic windows in Hall.

Stained glass armorial windows of Geoffrey Palmer, Christopher Turnor and Robert Hyde

Receipt for the painting of the arms of Palmer, Turnor and Hyde by Andrew Hall, 1660 (MT/2/TRB/19)

Educational Traditions Revived

The effects of the Restoration were also felt on the educational side of life at the inn. Admissions of students relative to the other three Inns rose after 1660, due perhaps in part to a decline in the popularity of Gray's Inn, tainted by associations with many prominent Puritans and regicides. The prominence of Middle Temple men such as Palmer, Turnor and members of the Hyde family may have contributed to its elevated status.

Lent and Autumn Readings, the centrepiece of the educational curriculum, had ceased to be given when the Civil War broke out in 1642, and had never been revived. Owing in part to external pressure from Edward Hyde on all four Inns, efforts soon began to effect their reinstatement. A committee of Benchers was appointed in November 1660 to 'consider concerning the choice of a Reader', promising to 'consider all ways for their ease, accommodation and encouragement'. Later that month, Thomas Mundy and Richard Allen were duly elected to serve as the next two Readers, thus restoring the practise after eighteen years. Despite this renaissance, Readings would, in the early 1680s, lapse once more, and there would not be another given until 1927.

Armorial Panel of Thomas Mundy, first Reader after the Restoration

The Changing of the Guard

Many Royalist Middle Templars had come to prominence under the new regime, representing something of a changing of the guard and a shift in the political mood at the Inn, which can be traced through the allocation of chambers. In 1644, the House of Commons had commanded the Inn to seize the chambers of 'Delinquents' - Royalists who had departed London to join the King. These included Sir Richard Lane, a former Treasurer whose chambers (along with his library) had been allocated to Bulstrode Whitelocke.

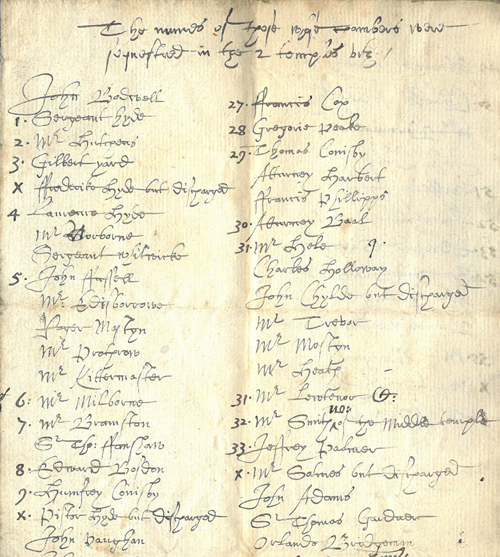

List of those whose chambers were sequestered in the Middle and Inner Temples (MT/1/MIS/3)

Another whose chambers had been seized was Sir Geoffrey Palmer, whose star was now definitively on the rise. Called to the Bar in 1623, he had been an MP in the tumultuous early 1640s, and taken the King's side alongside Edward Hyde, referring to his Parliamentary colleagues as 'a rabble of inconsiderable persons, set on by a juggling Junto'. After the outbreak of the Civil War, he had followed the King to Oxford and been appointed Solicitor General in 1645, before being captured and living a quiet life in London throughout the 1650s. Within a week of the Restoration, he had been made Attorney General, knighted, awarded a Baronetcy, and been elected a Bencher of the Middle Temple.

Engraving of Sir Geoffrey Palmer, Attorney General (MT/19/POR/531)

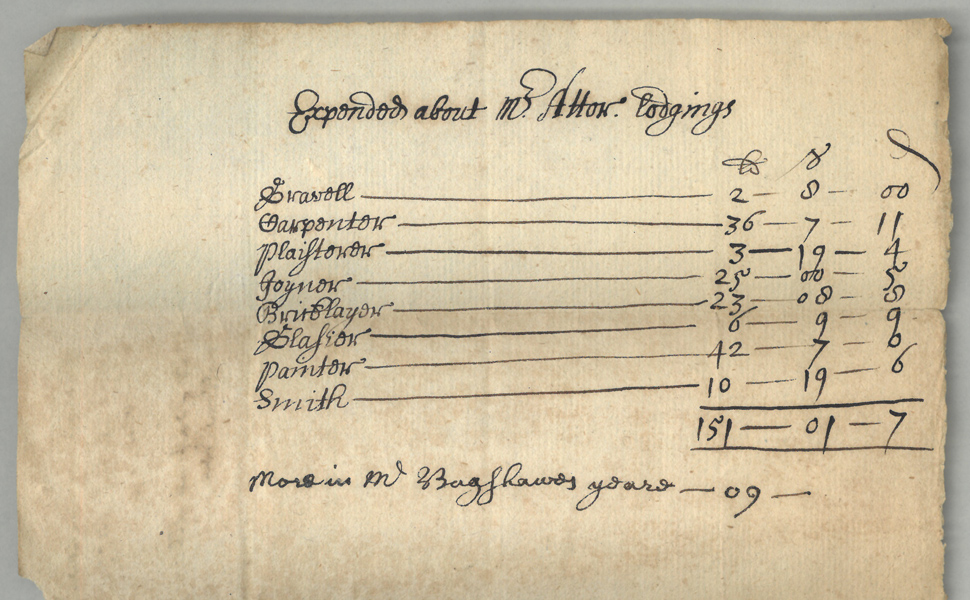

The Benchers were 'very desirous to accommodate Sir Jeffery Palmer with a Bench Chamber', and asked Robert Reynolds, who had until a few days earlier been Attorney General himself, to give up his chambers. A few weeks later, Bulstrode Whitelocke agreed to surrender his own chambers in Palmer's favour - two sets in Brick Court, including those formerly Sir Richard Lane's, once again changing hands with the shifting political mood. Palmer lost no time, it seems, in arranging for extensive renovations to his new quarters (at the Inn's expense), and a schedule of costs survives for sums 'expended about Mr Attor[ney's] lodgings', amounting to £151 - worth nearly £16,000 in today's money.

Schedule of Costs expended on Geoffrey Palmer's chambers (MT/2/TUT/24)

Middle Templars Beyond the Inn

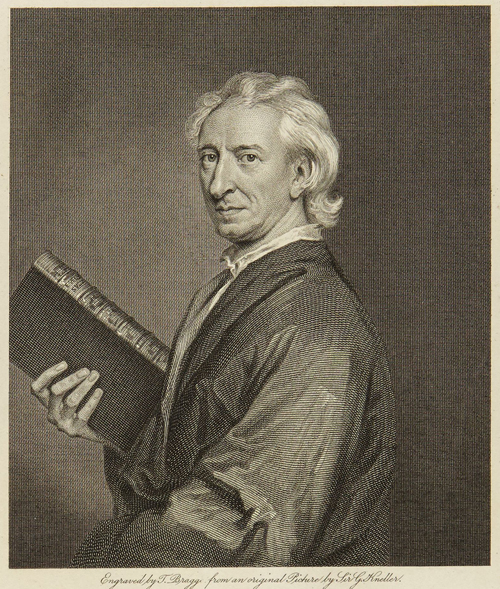

Many members of the Inn thrived after the Restoration in fields beyond the law. John Evelyn had spent much of the interregnum travelling Europe and refused public office under Cromwell. His loyalty was rewarded, and he served the new regime in many capacities, including as commissioner of the Royal Mint and overseeing the care of sick and wounded seamen during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. A polymath, he wrote on a diverse range of subjects including horticulture, theology and air pollution, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society in November 1660.

Engravings of John Evelyn and Elias Ashmole (MT/19/POR/268, 22)

Elias Ashmole, also associated with the Royalist cause in the Civil War, spent the 1650s quietly in the study of alchemy, antiquities and heraldry, before joining the Inn and being Called to the Bar in 1660. At the Restoration, he was appointed Windsor Herald, Comptroller-General and n Accountant-General of the Excise, lucrative positions which enabled him to assemble a considerable collection of antiquities, books, plans and other curiosities. Much of this collection went on to form the basis of the Ashmolean museum in Oxford, though a significant part was destroyed in the Middle Temple fire of 1679.

King Charles II, attributed to Sir Godfrey Kneller

By the time King Charles II's portrait was hung in Middle Temple Hall a few decades later, the flood of popular affection seen at the start of his reign had faded. Disasters such as the plague and the Great Fire of London, coupled with the mishaps of the Second Anglo-Dutch War, were seen by some as God's punishment for the immorality of Charles' court; these national calamities had also led to the impeachment and exile of Edward Hyde in 1667. Nonetheless, the impact of the Restoration on the Middle Temple was felt far more deeply than some sore heads on the 30 May 1660 - in the revival of long-dormant social, cultural and educational practices gone by, the changing of the guard in its senior governance, the commemorations in the fabric and aesthetics of the Inn, and the flourishing of its members in society.