If you have ever visited or dined in Middle Temple Hall, you will have struggled to miss the many armorial panels adorning its walls. These panels, which also adorn the Bench corridors, total over 700 in number, and span over 400 years of history. This month, we delve into the history of the production and display of armorial panels at the Inn, as well as exploring the preservation and conservation work undertaken in the present day to ensure the survival of this unique collection.

Print of the interior of Middle Temple Hall in which the armorial panels can be seen on the walls, 1800.

The majority of armorial panels on display represent those who have served in the office of Reader at the Inn, and – since 1981 – those who have served as Treasurer. The panels cover the period from 1597 to the present day, excepting a gap of nineteen years which started with the cessation of Readings during the Civil War and continued to the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. (More information on Readers and Readings in the Inn can be found here: February 2019: Readers & Readings)

The panels themselves display the Reader or Treasurer’s personal coat of arms accompanied by certain information about that person inscribed below in Latin, a layout unchanged from the 16th century through to the 21st.

The concept of a personal coat of arms originated in the 12th century when knights displayed heraldic symbols on their shields as a means of identifying themselves while wearing armour. Over time, ‘rolls of arms’ were developed, lists stating who owned which design, maintained by the royal heralds. Eventually the system of coats of arms being issued became centrally regulated when, during the reign of King Richard III, various heralds became merged to create the College of Arms in London, who still issue coats of arms to this day.

Just as fashions change today, the designs and styles used on coats of arms have varied greatly over the centuries. The earliest examples in Hall used simple geometric patterns for easy identification on the battlefield. The panel of William Bastard (Lent Reader 1605, Treasurer 1613), whose coat of arms has a blue chevron and single star on a white background, is an example of this.

Armorial Panel of William Bastard, Lent Reader 1605.

As coats of arms evolved to become a status symbol used in everyday life, more intricate drawings of animals, birds, and plants to symbolically represent a meaning began to be incorporated. For example, a lion was used as a symbol of bravery and a pelican vulning (wounding) itself was a symbol of self-sacrifice. Another popular design feature was canting, the act of devising the coat of arms from a pun or play on the bearer’s name, which accounts for almost half of the nation’s heraldic designs. Some examples from the Inn’s collection are the arms of George Beare (Reader Lent 1632) which include three bears’ heads, and that of Sir James Cassels (Reader Lent 1941) which show three medieval towers.

Armorial Panel of George Bear, Lent Reader 1632.

The coat of arms is traditionally placed within a shield, the shape of which has varied over time in accordance with fashion. However, the biggest difference in shape can be seen on the coats of arms of women. Rather than the shield, traditionally associated with warfare, a lozenge (diamond) shape is used for the coats of arms of many women. At the Middle Temple, the panels of female Readers and Treasurers exhibit a mix between the use of lozenges and shields.

Armorial Panel of Barbara Calvert, Lady Lowry, Lent Reader 2001.

The production of coats of arms took off in the Tudor and early Stuart era, but it is not known exactly when the tradition of producing and displaying armorial panels at Middle Temple began. However, the earliest Reader commemorated by a panel is Richard Swayne (Autumn Reader 1597, Lent Reader 1609, and Treasurer 1607). A painter’s bill from 1697 evidences that there were over 100 panels at the Inn by then, as a payment of £25 (substantial for the time) was made, for what would have been, the re-painting of 113 existing coats of arms.

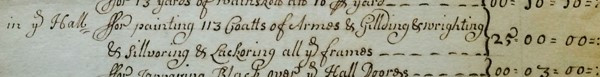

Painters Bill, 1697 [MT.2/TAP].

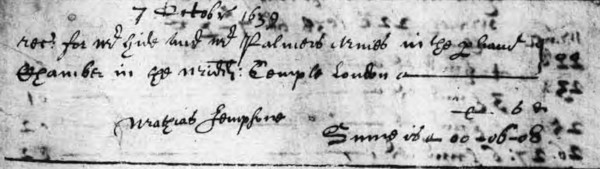

The above re-painting was completed by the Inn’s painter Mr William Thompson, who is shown in the Treasurer Receipt Books as having painted many other coats of arms in Hall too. For example, in 1702 he painted three for a payment of 16 shillings and again in 1707, painting one for 8 shillings. The Middle Temple also made use of specialist arms painters, for example in October 1639, the Inn hired Matthias Jemson to paint the arms of Mr Palmer. Jemson was a highly notable painter-stainer in London during that period as, in 1636, he had been privileged with a licence from the College of Arms to paint arms for funerals and other occasions.

Jemson's Painting Bill, Treasurer Receipt Book, 1639.

The panels were originally hung in the Parliament Chamber until it was decided by the 1696 Treasurer, Francis Morgan, that they had outgrown the space available and should be moved to the Elizabethan Hall. A joiner’s bill from 1697 shows a payment of £3 3s made for the work of fixing the windows, relaying the floor, and putting up the Arms in the Hall.

The panels continued to be hung on the Hall walls until the end of the 19th Century, when they had filled all available space. Henceforth new panels were put up in the corridors leading to the Parliament Chamber and the Prince’s Room (then the Smoking Room), where they are still hung to this day.

In 1705 the Inn's then Treasurer, Daniel Fox, commissioned an illuminated volume of the Readers’ Armorial Panels. This book presents all panels from 1597 up until 1938, when its production was disrupted by World War II. Following this, in 2015, a book displaying the panels, using a collection of high-quality photos, initially taken for a conservation survey, was produced: Armorial Panels at the Middle Temple, which spans from 1597 to 2016 (date of publication).

Page from the Illuminated Volume of the Readers’ Armorial Panels [MT/3/COA].

The panels (some over 400 years old) have shown excellent resilience throughout their life, even surviving the bomb damage to the Hall during the Second World War. However, in order to ensure that they can be displayed in Hall and the Bench corridors for years to come, it is essential that they are protected by professional conservation work.

Conservation of the Panels:

The Middle Temple panel collection has been part of a rolling conservation programme since 2015, after an initial survey was carried out on a selection of panels from different periods. The reason for this was two-fold. First, to determine their condition and to present conservation proposals for those most in need of treatment, and secondly to identify causes and patterns of deterioration, in order to provide preventive conservation initiatives that could protect the panels from future damage.

Panels from particular periods of time exhibit similar characteristics of aging. For example, many 17th century panels exhibition ‘bloom’, a condition that causes the varnish to appear cloudy, due to moisture having formed on or between varnish layers applied at different points in time. ‘Reticulation’, which is evident in the inscriptions of several 19th and 20th century panels such as that of Henry Ridgard Bagshawe (below), is caused by the different drying times of paint and glazes or varnishes.

Armorial Panel of Henry Ridgard Bagshawe, Lent Reader 1858 and Treasurer 1864.

Other panels exhibit structural damage such as loose frames, dented supports, and abraded paint – simple signs of wear and tear of a building that has been a hive of activity down through the centuries.

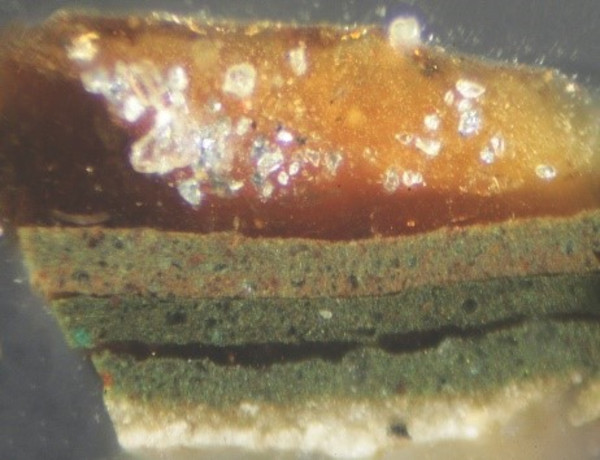

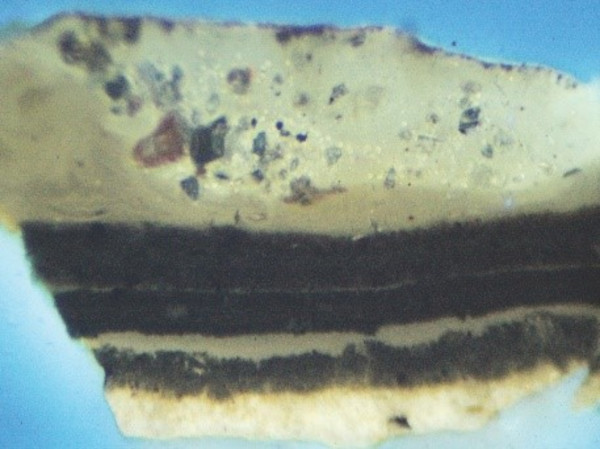

Conservation treatment is most effective when informed by knowledge of the materials and techniques used in the manufacture of an object. For example, a solvent used to remove a discoloured varnish may also inadvertently remove the paint underneath, as they have the same solubility. Through Middle Temple’s collaboration with City and Guilds MA Conservation students, it has been discovered, via analysis by UV, Cross-section and FTIR, that some of the 19th century panels have up to 11 layers of paint and varnish and that certain organic materials such as tree resin, oil based paint and shellac have been used, often partially mixed together as fresher layers of varnish, have been applied. Information like this allows conservators to understand the complex nature of these particular panels and to carry out safe treatments that maintain the integrity of the media.

Paint and varnish sample under plain light (top) and under UV light (bottom). © Copyright of T|Kenward.

To complicate the conservation picture further, at some point in the 20th century, the panels in Hall were varnished with a mixture of wax/resin to make the colours more saturated and render them more uniform in appearance. This is a varnish that ‘blanches’ or whitens, when in contact with common solvents and restricts the possible conservation treatments.

The most important priority for the panel conservation programme is, firstly to maintain the coherence and readability of the panels as an inter-related group, whilst at the same time focussing on improving legibility and halting active deterioration in individual panels. Secondly, it is crucial to discover as much as possible about the media and materials used on the panels of different time periods. To date, the conservation programme has seen over 40 panels treated by specialist conservators, several become the subject of student dissertations and a number of photo-reproduction copies produced to replace the most vulnerable panels.

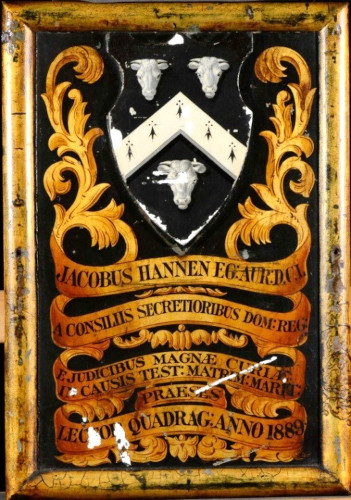

One example of how conservation can follow these guidelines whilst visually improving the appearance of a panel is recent work carried out on James Hannen’s panel from 1889. This panel is made from one oak board (some panels are made from 2 joined boards) with the shield attached by two large screws from behind and had previously been retouched.

The shield and inscription panel were dirty, the varnish was discoloured and both exhibited scrapes and chips that interrupted their legibility. The dirt was brushed off and then the shield was cleaned with swabs of a pH buffered compound. After much testing, the varnish from the shield was removed with acetone, retouched with watercolours, re-varnished with conservation wax and retouched again. Some of the chips and indentations were filled with chalk and gelatine in a water-resoluble medium but the older ones bearing old retouching were left. All the treatments and materials used are completely reversible.

Panel of James Hannen, before, during and after treatment.

The armorial panels at Middle Temple have been a prominent fixture for many centuries and provide a rich record of the Inn’s Readers and Treasurers, as well as being an important heraldic and artistic collection in their own right. Thanks to the efforts to ensure their preservation by the Conservation team, they will continue to be for many years to come.